Revolution: Russian Art 1917–1932 at the Royal Academy of Arts

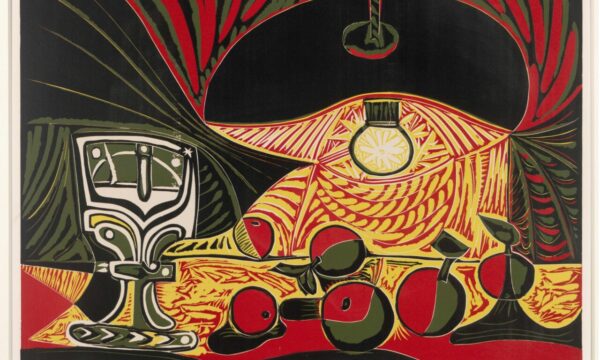

The Royal Academy of Arts’ new exhibition marking the centenary of the Russian Revolution charts the development of art through a unique 15-year period in Russian history: following the 1917 October Revolution, fresh opportunities were opened up for a new proletarian art to be developed for the Soviet State, allowing a diverse array of work to flourish until Stalin’s violent suppression of the avant garde in 1932.

The vast exhibition encompasses over 200 works from the State Russian Museum in St Petersburg, State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow as well as private collections, many never before seen in the UK. Films, photographs and documents are woven through the paintings, sculptures and porcelains are on display, including work by prominent artists, such as Marc Chagall’s stunning Promenade (1917-18) and Wassily Kandinsky’s Blue Crest (1917). Whole rooms are dedicated to artists like Kazimir Malevich, whose images such as Peasants (c 1930) broke conventions of modern art and presented the diminishing individuality of peasants under collective farming policies, and Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, whose pieces such as Fantasy (1925) were quietly radical.

The displays are organised around broad themes, taking in a sweep of the contrasting pieces that reacted and interacted with the tumultuous political climate following the revolution. Salute the Leader looks at the rise of Lenin’s power, his cult status after his death and the propaganda that aimed to spread Bolshevik ideas to a largely illiterate population, captured in the domineering image of Boris Mikailovich Kustodiev’s Bolshevik (1920). Man and Machine displays the figurative paintings, film and photos of male and female “proletarian worker heroes”, whose physicality and depiction as equals with machines promoted the success of industry and technology, including Arkadii Shaiket’s photo Construction of the Moscow Telegraphic Centre (1928), as well as changing ideals of femininity as held in Alexander Deineka’s Textile Workers (1927).

Brave New World shows the opening up of an original cultural world and Fate of the Peasants looks at how the introduction of collective farming impacted traditional rural life. Eternal Russia marks the resurgence of rose-tinted images of old Russia and the persistence of such images as part of the national identity. New City, New Society brings to life a brief seven-year period where new city lifestyles flourished under Lenin’s New Economic Policy, with posters and restaurant menus conveying Russia’s “roaring 20s”. The exhibition ends on a dark but necessary solemnity in Stalin’s “utopian vision of progress”, with stark images of sporting prowess, his grandiose public projects and an endless reel of portrait images of the individuals sent to Stalin’s Gulag, eventually shot or unable to survive the harsh conditions of the forced labour camps.

This fascinating collection uniquely brings together a whole spectrum of art, both rich in its own right as well as informative about the life and politics of a people during a tumultuous, dynamic, much-misunderstood period of Russia’s history.

Sarah Bradbury

Photos: Erol Birsen

Revolution: Russian Art 1917–1932 is at the Royal Academy of Arts from 11th February until 17th April 2017, for further information or to book visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS