A tender dissection: Leonardo da Vinci Anatomist at The Queen’s Gallery

Leonardo da Vinci’s astonishingly beautiful anatomical drawings are on display in the largest ever exhibition at The Queen’s Gallery, which presents 87 pages form Leonardo’s notebooks, including 24 previously unseen pages.

This is the second major exhibition of Leonardo’s works this year, after a highly successful show in the National Gallery. Although he wasn’t the most prolific author ever seen, fortunately he used to make piles of visual notes in the form of sketches. And though Leonardo wouldn’t even think of displaying his drafts, contemporary society love these sketches and eulogise his talent. Therefore, it is not a problem that some of the drawings were presented just two months ago. Granting that the first show was presenting him as a painter and the second as an anatomist, the two motivations are inseparable and together constitute his acclaimed oeuvre.

This is the second major exhibition of Leonardo’s works this year, after a highly successful show in the National Gallery. Although he wasn’t the most prolific author ever seen, fortunately he used to make piles of visual notes in the form of sketches. And though Leonardo wouldn’t even think of displaying his drafts, contemporary society love these sketches and eulogise his talent. Therefore, it is not a problem that some of the drawings were presented just two months ago. Granting that the first show was presenting him as a painter and the second as an anatomist, the two motivations are inseparable and together constitute his acclaimed oeuvre.

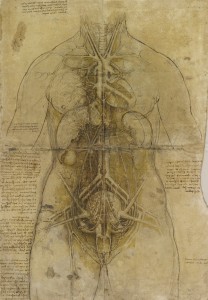

The display presents Leonardo as a super-genius, who not only has paragon skills in drawing, observation and performing dissections, but also as a scientist who first observed cirrhosis of the liver, whose perception worked as modern MRI, separating layers of tissues and bones and who figured out how the arteries and valves function, a hundred years before blood circulation was discovered. Moreover, some of the drawings are presented alongside and as almost identical to contemporary schematic, plastic educational models.

The first series of drawings were made in the 1480s, when Leonardo didn’t have access to human material (apart from a human skull obtained in 1489, remarkably portrayed and studied). However, around that time Leonardo was dissecting animals and illustrating ancient beliefs; among them is a drawing presenting an assumed structure of the brain, containing three ventricles or cavities, which were housing the faculties of mind and soul – the senso comune.

The first series of drawings were made in the 1480s, when Leonardo didn’t have access to human material (apart from a human skull obtained in 1489, remarkably portrayed and studied). However, around that time Leonardo was dissecting animals and illustrating ancient beliefs; among them is a drawing presenting an assumed structure of the brain, containing three ventricles or cavities, which were housing the faculties of mind and soul – the senso comune.

Later, by the beginning of the 16th century, Leonardo’s fame allowed him to work on human corpses, mostly the bodies of criminals with no claims for burial. Contrary to the common belief, autopsy wasn’t prohibited. The series of 18 studies conducted together with the professor of anatomy, Marcantonio della Torre, is characterised with the greatest clarity. Finally, he was left with researching animal anatomy including the detailed studies of oxen hearts.

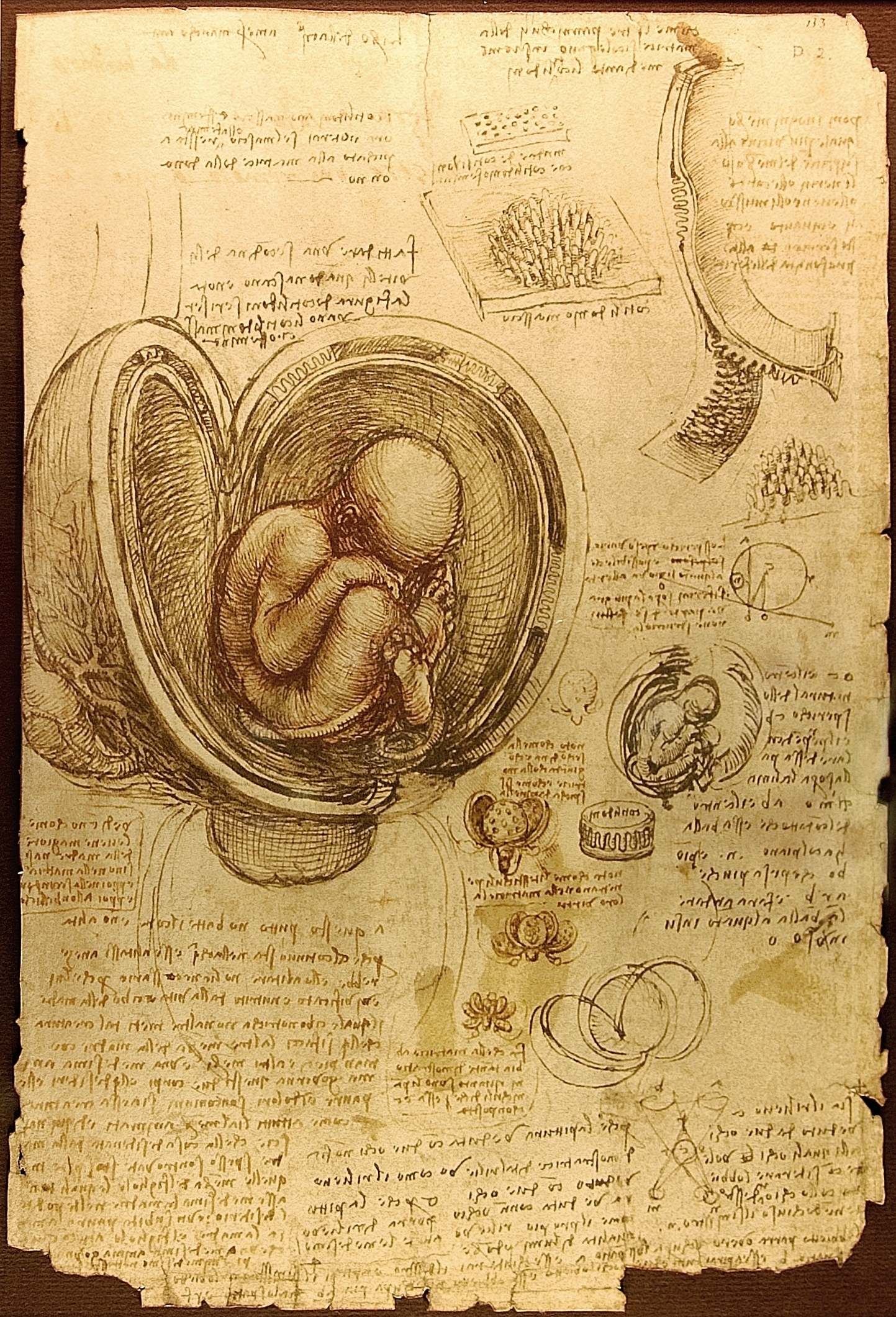

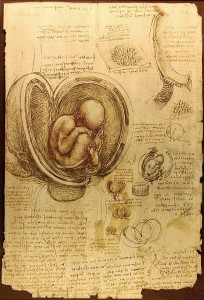

It is fascinating to witness Leonardo’s progress and to see how he revised unsound beliefs. It is equally fascinating to see that there were some topics which remained mysterious to him, for example, the woman’s uterus, as he tended to substitute it with cow’s structures. Leonardo was driven by pure exploration, but he was also looking for the principles of life, growth, movement and for the soul itself. His drawings were notes taken in this journey.

It is fascinating to witness Leonardo’s progress and to see how he revised unsound beliefs. It is equally fascinating to see that there were some topics which remained mysterious to him, for example, the woman’s uterus, as he tended to substitute it with cow’s structures. Leonardo was driven by pure exploration, but he was also looking for the principles of life, growth, movement and for the soul itself. His drawings were notes taken in this journey.

The display, curated by Martin Clayton, is accompanied by an iPad app, which not only presents all 268 anatomical drawings from the Royal Collection, but also contains interactive models, interviews and a magnificent feature allowing viewers to reverse and translate Leonardo’s eccentric mirror writing directly on the sketch. If only the app wasn’t priced at £9.99, it would be truly inspiring.

Apparently, Leonardo intended to publish a treatise in anatomy. Unfortunately, similarly to his famed contemporary Michelangelo, he had a habit and the bad luck of not finishing works. In 1519 Leonardo died leaving his assistant, Francesco Melzi, with a challenge of ordering the legacy. By the 17th century, an album containing Leonardo’s anatomical sketches entered the Royal Collection. It was not until the 20th century that his papers were finally published and recognised.

It is tempting to try and imagine how differently we would have looked at medicine if Leonardo had published his observations. Leonardo’s treatise would have probably diminished the famous On the fabric of human body published in 1543 by Andreas Vesalius, but could it change the whole development of medical understanding? The fact that we can recognise structures and techniques looking backwards doesn’t necessarily mean that they could accelerate the anatomical studies. Had Leonardo published his treatise, we may know him today as an outstanding anatomist. Instead we praise him as a brilliant artist and a fascinating polymath, whose countless talents we can discover and uncritically idealise.

Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomist is on display in The Queen’s Gallery until 7th October 2012. For more information click here.

Agata Gajda

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS