Why we need to stop romanticising mental illness in art

The link between mental illness and art is nothing new. Throughout the centuries, there have been many artists who have played the role of the tortured genius with aplomb. Nor is it without foundation, a 2015 study found that people in creative professions, such as painters, musicians and writers were, on average, 25% more likely to suffer from mental illness.

Many artists who are rightly revered have suffered from psychological illnesses, and “madness” has often been the inspiration or the subject of great art. However, we are at risk at drawing a false correlation between creativity and mental illness.

It is important that, as a society, we don’t credit mental illness for anyone’s artistic output. Romanticising not only diminishes the work, and remember that a person’s illness is not synonymous with their talent. In fact, it can hinder it.

The connection between mental health and artists

The link between madness and art stretches back centuries, and mental illness is a subject that has proved alluring to many great artists. William Hogarth explored the line between sanity and insanity in The Rake in Bedlam (1733), Theodore Gericault took on the subject in a series of paintings titled Portraits of the Insane (1822). Even The Scream (1893) by Edvard Munch, is seen as a comment on the notion of feeling sane in an insane world. For Jonathan Jones writing in The Guardian, Munch’s masterpiece represents the desire to scream out in pain and isolation under the wobbly sky which he says is a sane response to an insane world.

Mental illness is a subject that still proves captivating for artists. Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama, whose psychedelic work with polka dots has made her world famous, suffers from obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and has lived voluntarily in a psychiatric institution since 1977. According to the Tate Modern, her illness and her work are closely intertwined: “Much of her work has been marked with obsessiveness and a desire to escape from psychological trauma. In an attempt to share her experiences, she creates installations that immerse the viewer in her obsessive vision of endless dots and nets or infinitely mirrored space.”

According to Kari Stefansson, founder of the genetics company that conducted the 2015 study into mental disorders and creativity: “To be creative, you have to think differently. And when we are different, we have a tendency to be labelled strange, crazy and even insane.” The problem is, this obsession with the idea of the cursed artist could, and does, turn into a self-fulfilling prophecy for many, often to the detriment of the artists themselves, and quite possibly their art.

Mental illness can hinder great artists

What if, rather than there being no link whatsoever between creativity and mental illness, there is evidence that mental illness can hamper the talented and creative. Sarah Graham is an artist whose photorealism work on kitsch subjects such as sweets has been lauded by art critics and fans alike. She also suffers from bipolar disorder. Sarah Graham’s art is hugely popular, but according to the artist, this is in spite, rather than because of her illness. “It hasn’t helped my career. Sometimes I’m poorly for four months and I’m not able to work for all that time. It can have a really negative impact.”

Van Gogh himself felt the same way, in one of his last letters he wrote: “Oh, if I could have worked without this accursed disease – what things I might have done.”

We can point to some of art’s greatest masterpieces and the mentally ill artists who created them and see the correlation, but what we can never see are all the masterpieces that have never been painted, because the artists lost their lives, or their minds, before they had the opportunity to paint them.

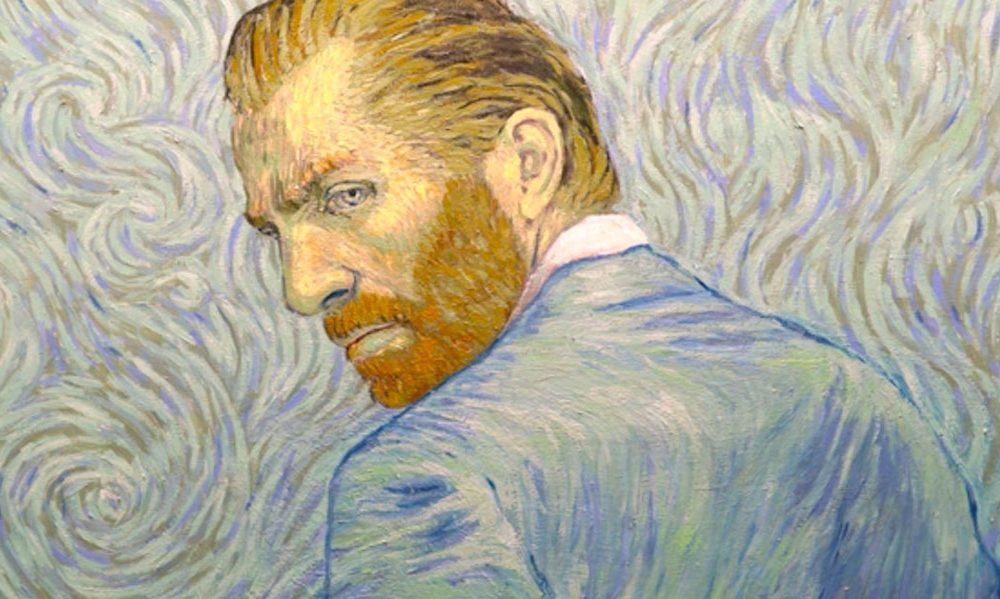

Vincent Van Gogh is often presented as the archetypal “tortured genius”. He was undoubtedly both. We can look at his masterpieces, and ponder if his illness played a part in his paintings. Vincent Van Gogh committed suicide at the age of 37. How many years did he deprive himself? And how many great works of art did his illness deprive the world of?

Albert Rothenberg, professor of psychiatry at Harvard University is not convinced that there is any merit to the “tortured genius” stereotype. He believes there is no good evidence for a link between mental illness and creativity. Instead, Rothenberg denounces the myth as a “romantic notion of the 19th century”. On Van Gogh, he claims he just happened to be mentally ill as well as creative, adding creative people are generally not mentally ill, but they use thought processes that are of course creative and different.

Art can treat mental health issues

Although we are at risk of romanticising the mental anguish of certain artists, we shouldn’t shy away from the subject. The number of unexpected patient deaths reported by England’s mental health trusts has risen by almost 50% in the last three years. If art can help us better understand illnesses, that can be a good thing.

According to mentalhealth.org, creative expression is helpful to healthy human development and recovery from mental distress. It’s hardly surprising that art therapy has found to be beneficial for people with mental health issues. Art therapy is thought to be a useful tool in tackling emotional wellbeing and can help people who struggle to communicate their thoughts.

What’s important is that as a society we continue to seek to learn more about mental health. 4 million people in the UK suffer from bipolar disorder, and in the UK about 1 in 5 people will need treatment for a mental health problem during their life. Whether or not there is a tangible link between creativity and mental illness is up for debate. However, it is important for us to debunk mental illness myths where we find them. Mental health problems aren’t synonymous with talent or genius, and they certainly don’t help great artists create their masterpieces.

The editorial unit

Photo: Loving Vincent

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS