Who’s Gonna Love Me Now?: An interview with directors Tomer Heymann and Barak Heymann

Who’s Gonna Love Me Now? is the British-Israeli documentary film following 40-year-old Saar, an Israeli man living in London and part of the London Gay Men’s Chorus, who is seeking reconciliation with his estranged conservative family back in Israel after being kicked out of a religious kibbutz, coming out as gay and being diagnosed as HIV positive. I sat down with the directors, brothers Tomer and Barak Heymann, to find out what prompted them to put Saar’s story on the big screen, the challenges they faced filming the movie’s many intensely personal moments, and the impact of the film on Saar, his family and people across the world.

Hi there, lovely to meet you both. Thanks so much for taking the time to speak with us. So, Who’s Gonna Love Me Now? – what inspired you to tell this story?

Tomer Heymann: 23 years ago I met this beautiful man in the streets of Tel Aviv. I don’t know whether to call it being in love but there was an amazing click between us. We spent 24 hours together. It started as a one night stand between two guys who were living crazy lives in Tel Aviv and had a strong attraction – intellectual, physical and emotional. We were talking, kissing and sharing whatever we had on our minds. And in the morning when he needed to go, we went to the corner and he changed to dress as a Jewish religious guy. I was shocked. He took it out around the corner, this Jewish costume, and I was surprised. He hid it, he didn’t talk about it. When I told him “let’s talk about it, let’s meet again, I really want to see you again,” he said, “I would really like to see you again, but I don’t think I will have the chance. I’m moving to London and I have issues with my family and my father. I’m in a lot of conflict and in a bad situation in my life.” He hugged me, went into the street and that was it, it was over. Then a couple of years later, I met him again by mistake in the street and I asked him “What are you doing here?”. He told me, “I’m here visiting the country, I’m living in London”. And I ask him, “Can I have an interview with you? As I remember you have a very interesting, unique story”, though I didn’t remember the details. So he was sitting in my apartment ten years later and he opens up to me and tells me: “Two years ago I was diagnosed with HIV, not a long time ago. I want to talk about it with my family”. He explained to me what had happened with his life – how far he went with drugs, with orgies. I appreciated he didn’t blame the other guy, he took responsibility. It was the first person ever in my life, close to me, not from the media, that talked to me and said “I have HIV”. And even me – as a gay guy, open – even I was a bit, you know, taken aback. I wanted to use the interview for a project I was doing in Israel, but I got a phone call from Saar, a few days after, and he says, “Tomer, I gave you this interview, I have been very honest with you, but I have to ask you, promise me you will never ever use it, I cannot do it to my family. I don’t think they will ever agree to be on any platform of media, TV or movies. Please, please promise me”. And I said: “Saar relax, I’m not going to use it. I’m very sad about it but I’m not going to use it”. And he said: “It has put me at risk. My family is a very conservative Jewish family. It might cause huge damage to me and to them,” and of course I respected it. And then the third meeting with him was in 2011 – I was getting a prize about human rights in movies, and I published it on Facebook. So he saw it and realised I was here in town and asked to meet. I remember I didn’t tell Barack I was going to meet him. But I knew that I wanted to see what had happened to the guy I had met more than 20 years ago. We talked and he reminded me, “Remember that I asked you to delete the old footage because I was afraid and full of fears?”. And he was very honest and said, “I have the feeling I want to do something with my life and my issues. Maybe it’s time to create a movie about this story”. And immediately I called my brother and I was really excited. Because Saar was still with me – something about his story, this lonely guy in this world looking for meaning and answers. And I shared this with Barak and I said: “Let’s do this movie together, let’s choose it as our next project.” And then Barak got the picture. So it was a very long process.

The film is intensely personal, some moments are even difficult to watch – such as some of the reactions of Saar’s family or the intimate moments that pass between Saar and his mother. What were the challenges and opportunities of filming and putting that on the screen?

Barak Heymann: Firstly, you have to remember that for every moment you see in the film there are hundreds of moments that are not in the film. And the reason I’m mentioning that is because it’s not like their life is one long roller coaster of peaks and dramas and conflict and crazy scenarios. There are also a lot of moments that are more like daily stuff and there are also moments of humour and there also moments of being close to each other. Of course when you make a film and you want to tell a story then you edit it and you focus on what you are interested in. But our filmmaking style is always based on long term process and not having a script. So we never want to narrow our perspective by thinking “this is what we a looking for, this is where we want to aim, this is what is interesting for us and everything outside of those clear borders is not relevant”. No, for us we had this very strong feeling about this guy that Tomer met in his private life many, many years ago. We felt there was a very interesting, emotional and universal conflict between him and his family, between him and himself, between him and Israel, and we felt that whatever was going to happen it was going to be very emotional and interesting. When we were going to shoot the family and him, of course we were very attracted to the conflictual moments, but also covering many other aspects of his life.

TH: We were witnesses, we were in very strong intimate moments that in my wildest dreams I didn’t realise would happen during the filming of the movie. I know which moments you are talking about: being there in the kitchen with his mother or back at his home with his family around the table when the seven brothers and sisters attack him and have this unbelievable conversation. I remember myself shaking while shooting it with the camera. Especially the moment in the kitchen in London with his mother when he cut himself and there was blood – some directors would choose to close the camera and say “this is too much, it’s too personal. From here, let’s talk about it without a camera. Let’s give them some privacy, it’s not for the movie”. It’s a choice. I remember I was in a very high level of awareness – I looked at the cameraman to be sure that he was not closing the camera. That we were recording it. And I trusted us, that we were going to use it in a very fair and honest way.

BH: But for us as filmmakers it is natural that we are there, even when it’s difficult. We are happy that we have those intimate and intense and provocative moments. So in some ways this question should be addressed to the family: “How come you allow those brothers to come with their cameras, and to document those moments that are obviously very, very difficult?”. And this is why I said what I said because this is part of the answer, because we are not there only at those moments, such as when Tomer was shooting in London when the mother was coming to visit Saar. Yes you have those crazy moments, like in the kitchen with the blood, but there were also many other moments he was shooting, which were much more relaxed.

TH [to Barak]: She’s not talking about other moments, she’s asking about specific moments such as when the mother and Saar were not aware of the camera while it was happening.

BH: We became in some ways, part of their life. Those five years from 2011 until February 2015 when we premiered the film at Berlinale – actually up until now – we became part of this family life. When I call Saar’s mother, and I have been doing it on a weekly basis now for six years already, she calls me “my son”. This is how she calls me, but in Hebrew: “How are you my son?” And I say, “don’t you have enough with your seven kids?” and she says, “what can I do? You and Tomer are like my sons for me because you’ve been with us in all the most terrible moments and in all the most happy moments”. We became part of their life. So when you become part of the life of someone, then in some ways it makes it a little easier to digest those very dramatic, problematic, conflictual moments because there is a spectrum of feelings that you are covering and not only those that you pick up with your camera. It makes it more natural for them, and for us, to be there. This is why I mention it. And this is also very unique about our filmmaking style, because many other directors – and I’m not saying that we are any better, it’s just our nature – we never write a script, you know. We have a very vague idea and very vague feeling about what is interesting for us but we never have a script. And while other directors maybe work with a strict budget and deadline, like “we have 22 days of shooting and we must deliver this film in August 2012”, we are not like that. We are going to finish the film only when we feel that it is done, and whatever it takes to make it, we will do. And we shoot a lot, a lot of days, which makes it much more costly, because the more footage you have, the more complicated the editing process. It’s a very different and dangerous way of making films and one of the reasons the support of the BFI was so crucial to make this dream come true.

What do you think the impact of this whole process has been on Saar and his family? And what do you think will be the impact on the wider world on seeing this film? How might that differ between places like London, which is quite open and has platforms like the BFI Flare Festival, and places in Israel, for example, where more conservative views are under the spotlight in the film?

BH: I can tell you that many, many different types of LGBT film festivals were inviting the film; for example we were in St Petersburg in Russia, in very hardcore places for gay people. But it is very important for both of us to screen the film not only for gay communities, but to screen it worldwide at many different kinds of events. Because on the deepest level of this film I think it’s about communication between people, and about the possibility of people to be better people – to change, to reconcile and go through transformations. Like the parents of Saar, they go from being so homophobic, so ignorant, so crazy in a way, and so brutal, to become so supportive. There is something very optimistic and universal about that message. So this is about the second part of your question, about the impact on people. Because I think you don’t need to be gay, you don’t need to be HIV positive or Jewish or from a kibbutz or from Israel or from London in order to get something deep to your heart from this film, about the need of clear and straight and honest communication between people.

And for Saar, do you think it was cathartic for him to make this film or were there times he might have found the process traumatic?

TH: I think it surprised Saar; it gave him an ability to see something about life and to see something about his specific life. Lately I’ve been thinking that, for me, the movie is about pain – what are you doing with your pain. You have a lot of pain in your body, not just physical pain, all of us have. We all have pain, either about something that happened in your life, you are sad about something, you lost someone. I call it vomiting your pain, which means Saar got to a turning point in his life, he decided to work differently with this feeling of pain, and tried to heal himself. He realised he still had time to fix and create a better life before it was too late. I heard so many stories and I listen to so many other cases where people wake up one day from this pain and want to do something about it, but it’s too late – you don’t have your parents, your children, your lovers around you anymore, you have nothing to work with.

BH: It’s so funny, he’s talking about pain and I see it completely differently – because I think it’s about love. Then the rest is the same because many people wake up one day and they realise that the people they love, it’s already too late to rebuild the connection with them and to recreate trust with them. And I think this was also part of the motivation of this family and of Saar, to be part of such an intensive [experience] – not that they knew it was going to so intensive – but still it was clear that we were going to touch sensitive issues and I think Saar’s family and Saar, they had a lot of love for each other, and even longing for each other, but they lost the ability to enjoy it and to give it a place in their lives. And the film helped them through a lot of blood, a lot of pain, a lot of tough moments, a lot of terrible conversations. It gave them the ability and the freedom to get back in touch with each other. And this is a huge change in their lives.

And have you been surprised by the reactions of people who have seen the film?

TH: We were surprised by the young generation of audience who came to see the movie, people whose lives are really far from Saar’s life – they are not Jewish, they don’t have many brothers or sisters, they are not gay – and still it took them and shook them and forced them to ask questions about their life. We get emails, SMSs, phone calls everyday – reactions from people who don’t even want to explain to us their specific problems in life but that after watching this movie they decided to take action in their lives, they woke up and wanted to do something: a father called his daughter after 20 years; two brothers who have fought and refused to sit around a table say “let’s talk about it”. I can give you more examples.

BH: People change their profession after many years because they see the film and see that it’s possible to change because – though I don’t want to make a spoiler for those who haven’t seen the film! – you can see in the film the main character is doing something revolutionary in his life. And this is something that most of us are afraid of.

TH: And we hope and believe that for people in the UK, the film will be a strong mirror about how to deal with outsiders. It’s about being an outsider in London and how you deal with it.

Sadly we’ve run out of time – but thank you both so much for speaking with us!

Sarah Bradbury

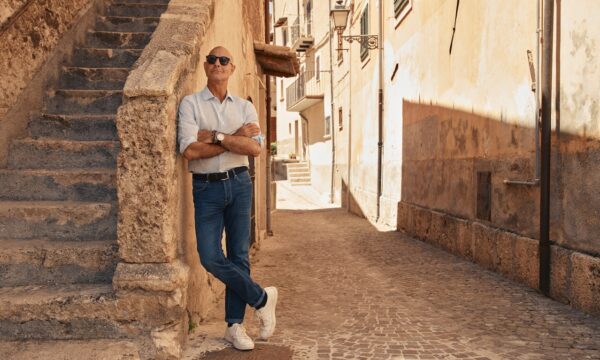

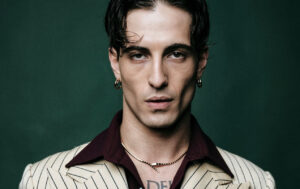

Photo: Heymann Brothers Films

Who’s Gonna Love Me Now? is released in selected cinemas on 7th April 2017.

For further information about Heymann Brothers Films visit here.

Read our review of Who’s Gonna Love Me Now here.

Watch the trailer for Who’s Gonna Love Me Now? here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS