Giacometti at Tate Modern

You may think you know Alberto Giacometti, but you don’t. This fact is made perfectly clear to every viewer as they step into the first room of this expansive new retrospective at Tate Modern. There, turned expectantly towards the visitor like students waiting for a lecture, are rows of heads. Sculpted between 1917 and 1960, these figurative faces demonstrate the extraordinary breadth and depth of Giacometti’s artistic style and practice.

From his earliest youthful forays into working with clay to elongated faces cast in bronze, via experiments showing the influence of Surrealism, ancient Egyptian art and the vagaries of plaster, this room offers a sum of the exhibition in miniature. The tone set is one of art historical precision with a humanising and anthropocentric slant. It’s a tone followed by the rest of the show and that effectively illuminates the artist’s work, which is at once concerned with the technical precisions of sculpting and drawing and with the wider condition of humanity in the 20th century.

Giacometti isn’t often seen as a Surrealist, but as the exhibition effectively lays out, some of his most successful early works were eagerly accepted and praised by members of the movement. There are table-top pieces in the style of board games with frustratingly opaque rules, and a number of startling “disagreeable objects” that are sexual and violent in equal measure.

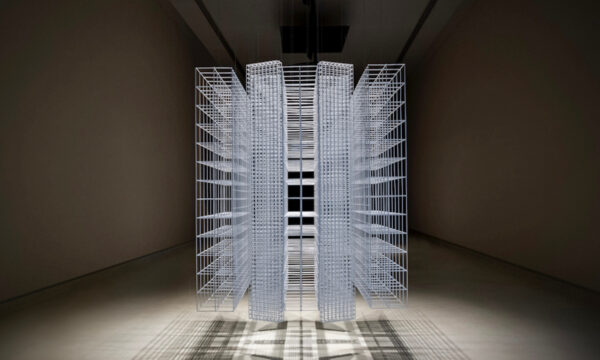

Even in these early Surreal works, scale is always a key occupation of Giacometti’s. This becomes even clearer when he leaves the Surrealist movement behind, demonstrated by a beautifully curated room of tiny figurative sculptures. Mostly made in a hotel room in Geneva when he was denied re-entry into France during the War, they are exquisite in their littleness, like a good friend glimpsed from a great distance. One is so tiny it could almost make you cry.

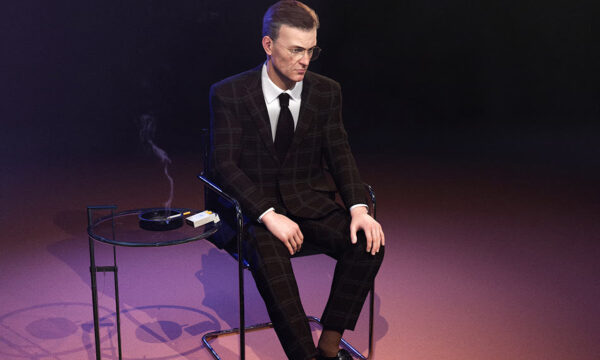

When most people think of Giacometti, they picture his bronze walking men and standing women of the 1950s. But the substance of these creations lies in the evolution of the artist’s practice up to this point, and particularly in the plaster works that form their basis.

One of the greatest moments of this exhibition comes in the presentation of eight of the nine surviving Woman of Venice plaster works, produced for the Venice Biennale of 1956. These pieces, which were originally shown in plaster but later coated in a thick layer of shellac for casting in bronze, have been especially restored for this retrospective. The protective layer has been removed and the full genius of the plaster works revealed. They serve to demonstrate that it is plaster, with all its fragility and malleability, that shows the true essence of Giacometti’s creations.

In the final room, two standing women (later formulations of these plaster pieces) tower like sentinels as visitors leave the show. They stand as silent witnesses to Giacometti’s perennial power and to this superbly curated exhibition from Tate, which is both elegant in its formulation and subtly challenging in its art-historical repositioning of a much-loved master.

Anna Souter

Photos: Erol Birsen

Giacometti is at Tate Modern from 10th May until 10th September 2017, for further information or to book visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS