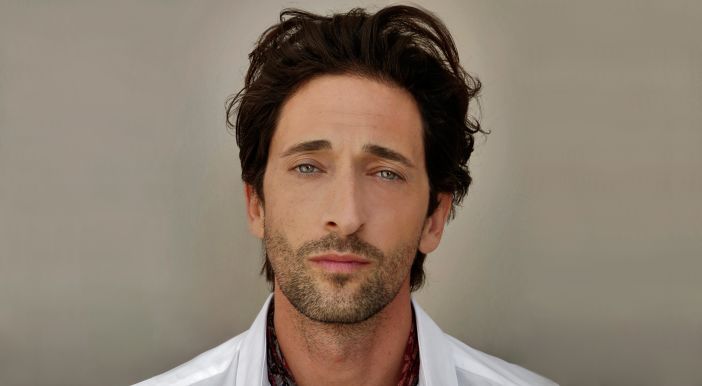

Adrien Brody receives 2017 Leopard Club Award for lifetime achievement

Oscar-winning actor Adrien Brody is this year’s recipient of Locarno Film Festival’s Leopard Club Award for lifetime achievement. Brody earned fame in Roman Polanksi’s The Pianist, for which he won his Academy Award for Best Actor. A respected painter as well as the muse of filmmakers such as Wes Anderson, M Night Shyamalan and Spike Lee, Brody reflected on his life and work over the course of two press conferences held at the tip of Lake Maggiore.

Brody began by recalling the start of his career. “My father said to me before my first audition, ‘Go in there like you already have the role.’ It was the best direction I could have received. It gave me ownership of the character. It wasn’t me borrowing material and offering an interpretation anymore.”

Of his defining work in The Pianist, Brody described it as “a unique opportunity in one’s lifetime. The greatest responsibility I could take on as an actor. Not only to reflect the experience of someone who lived through the horrors of World War II and the Holocaust but to create a memoir to share and include Roman’s own tragic experiences – to unsentimentally offer a window into this time.”

“I was 27 and had not fully grasped the perspective I developed as a result of making the movie. I gained a lot of my understanding of the potential for suffering and the need for us to acknowledge our blessings we all take for granted from time to time.”

The actor described his bodily transformation for the role: “There was a physical shift – you cannot act starvation. The rapid weight loss can only come from a starvation diet, which gave me greater insight into the shift in how you view yourself and the world around you and the desperation that comes with this.”

“In the film there is a slow degradation of the character. My character is stripped of his civility and his humanity. His erosion is a metaphor for a broader erosion, this whole civilisation being reduced to a shell of what it was.”

Music was of course integral to the film. Brody outlined his approach for replicating Wladyslaw Szpilman’s ability at the piano. “I had to learn to play these portions of Chopin. That was strenuous but it helped me because of the starvation I was also working towards. Music soothes and it shaped what I learned from one day to the next. I stayed at home and connected to the music, which ultimately gave me a sense of truth and connection to the character. The nuances in interpreting the composition each time – it was phenomenal.”

“In the rehearsal period I had seen a homeless person, who due to the weather had hands that were inoperable, gnarled. In turn I stripped away a musician’s gift and sensibility. From the cold and the malnutrition, I restricted the movement of Szpilman’s manual dexterity. It was much more symbolic when he went back to play pieces that were once easy for him. Now he found himself having deep difficulty. If I hadn’t done those hours of lessons and research, I wouldn’t have achieved the subtle and nuanced expressions with my hands.”

This role would have a lasting effect on Brody. “I was depressed for a year after The Pianist. It was mourning. I was very disturbed of the awareness that it had opened up. It was my journey into manhood. It reaffirmed my values and kept me grounded after the sea of access offered post-Academy Awards win. I had recognition of who I must be and who I must become.”

Before his most famous performance, Brody acted under Spike Lee’s direction in Summer of Sam. This sculpted his acting talents. “Working on the film was an amazing coup, as we shot in New York where I’m from. It had a vitality, Spike’s connection to that city. It was about judgement based on physical appearance. I had to shave my head, style a Mohawk and have these crazy liberty spikes, which were a hairstyle of the time. I wore chains with skulls and tight clothes I wasn’t used to. I literally witnessed people walking on the other side of the street, looking at me critically or suspiciously. This was in New York!”

On his collaborations with celebrated auteur Wes Anderson, Brody was effusive. “Wes is such a genius, a unique storyteller. You look at any of his images and you say, ‘Look, that’s a Wes Anderson film.’ It’s such a privilege to be welcomed into that fold. I care greatly about him – he is a great friend and confidant. He’s one of the earliest directors to allow me to be funny. I crack myself up all the time, whether I am doing something ridiculous or when I have a thought. I want to share that brightness and beauty.”

Regarding Night Shyamalan’s The Village, Brody explained his preparation for the character of Noah. “He was mentally handicapped. I didn’t want to play it too broad. People like Noah have limited learning capacity but I wanted to create a character that was childlike and endearing but capable of making great mistakes. I also wanted to work with Night Shyamalan, who had made some great films, and with Joaquin Phoenix.”

Of Peter Jackson’s King Kong, in which Brody starred as screenwriter and Ann’s main human love interest Jack Driscoll, he recalled marvelling at how the movie was produced. ”While filming the technology had already changed. They redid the three-dimensional scanning [for the special effects]. We are now light years beyond that. In film, we are fortunate to have the imagination and the resources and the people with the technical ability.”

Brody also explained his recent move into Chinese cinema. “China provides new fans of movies. They are more dependent on going to the theatre than in our culture. They are committed to seeing movies and they’re building cinemas left and right. With laptops, iPads, iPhones now, we don’t want to lose the cinematic experience. In this sense, China was a new market for me.”

Less happily, Brody’s work on Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line was instructive. He spoke with rawness on the subject, two decades on. “It wasn’t the easiest experience but it gave me a great understanding. My role was reduced dramatically from what we set out to do. But the making of the film was profound. I lived in the jungle. I was ostracised from my group.”

“I poured my heart into the movie and worked very hard. Terrence made a different movie that didn’t adhere to the script. I felt a level of loss. I gave that level of commitment. I played a solider and that’s what soldiers experience coming back to society. That’s the journey and I did not receive the recognition that I had hoped for, although I gained fortitude and an understanding of loss.”

The actor also spoke of his dalliances in the art world. “Painting is a real blessing. I painted and drew when I was young for many years. I was accepted into art school for drama. The beauty of painting is a sense of creative autonomy that is not afforded to the actor. It is a newer language for me to uncover and to convey my own perceptions of the world.”

“My first series Hot Dogs, Hamburgers and Handguns referenced gun crime – it being as widespread as hamburgers in America. The reality of what I grew up with was violence. It’s a complex dilemma that I was able to explore. Being anonymous is a great luxury and it allows me to access my vulnerability and my own flaws and represent them. The baggage of celebrity comes into play when you reach a certain level. The ability that you lose is to observe others without being observed first.”

Brody stated that he wouldn’t necessarily turn down a superhero character. “I’m open, I’m experimental. In light of what Iron Man has done for [Robert] Downey Jr, and what Downey Jr has done in return, for example. There have been discussions over superhero films, but it has not been quite right. I don’t have an aversion to it as long as a great role is presented.”

On the current appeal of television for serious actors, Brody was supportive but offered some caution of its effect on cinema. “There is less of a range of independent filmmaking at the moment. Lots of films in the 1970s were at a top level, with great examples of wonderful narrative films that were complex, even European in sensibility.”

“But now the stigma of a film actor doing television has long gone. In the right series there’s a lot of room for an actor to develop a character, and that’s very appealing to me. Breaking Bad is a good example. But there is now a glut of television with too many options.”

“The commitment to act on TV is enormous – a film lasts about three to six months. I fully immerse myself and then I am free. I’ve declined TV offers as a protagonist because it lasts five to seven years if it’s successful. I have a guest role in Peaky Blinders and I’ll be in season four. While the process is not that dissimilar to filmmaking, it’s just a commitment issue.”

Finishing up, Brody outlined his basic approach to acting. “I’m really searching for roles that can do two things: connect to a wider audience and connect to my intellectual expression. You don’t have to notice my technique, but it should haunt you. It should tell you that this character is not me.”

Joseph Owen

For further information about Locarno Film Festival 2017 visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS