An interview with Olivier Assayas at Locarno Film Festival

Esteemed film critic and director Olivier Assayas heads the jury at this year’s Locarno Film Festival. We interviewed Assayas at Hotel Belvedere, a few cobbled streets up from Piazza Grande and spoke to him about his influences, previous directorial work and his thoughts on the festival.

Hello Olivier. What does the Locarno Festival represent for you?

I’ve been coming to Locarno for a while and always lived the experience. I think it’s one of the festivals most open to new forms of filmmaking verging on the experimental. You have a sense of the direction of cinema by coming here.

Do you see any differences between Cannes and Locarno?

When I was in the jury at Cannes the president was Robert De Niro so you can see the difference. Cannes is more formal but fascinating in its own way. It’s not the same thing watching movies by filmmakers you’ve never heard of and filmmakers who have a long history of work.

This festival is particularly challenging due to its heterogeneous nature.

Yes. It’s difficult because some of it is on the border with art installation. A lot comes form the art world and then you have more classic movies and postmodern filmmaking. The difficulties are in finding the right way of evaluating the work.

In which way does experimental cinema influence you?

Often experimental filmmaking is considered a world of its own, which is not how I see it. But you must integrate experimental film in the history of mainstream cinema. There would have been no Fassbinder or Almodóvar without Warhol, and so on and so forth. Some experimental cinema is central to the medium at this moment.

What do you think of television as a medium?

It’s experimental certainly. But the cinema I relate to is on the big screen. My central experience is sitting in a theatre with a crowd watching a movie.

What’s the difference between being a film critic and a jury member?

I have forgotten what film criticism is about. You see movies without the buzz. They come at you out of the blue. You have not heard about them – you have not seen what other people are writing about it. You have a virgin experience. I shut myself off so I can have some genuine experience of them. As a jury, we watch them together.

What intrigues you about special effects?

There were two major events in the early 1980s when I was writing: a discovery of Chinese cinema, of which I was attracted to its novelty; and special effects, which transformed the nature of cinema. I remember saying that the issue is not science fiction, it’s special effects. The texture of cinema is changing. Technology is an essential part about how the world is changing. I always liked the documentary dimension of cinema. I’m interested in how technology transforms us, the human experience. Cinema is a very new art and a very old art, which is defined by a technology that is changing so much.

How do you choose the music for your films?

The songs come very late. Gradually, in the editing room I end up trying things. I dropped the idea of working with composers because I felt tied. I end up with a score that has to fit the film. So I decided I’m not going to use a musician. Every song in the film has to be like a small miracle. The problem now is that you have indie rock in every movie, no matter how stupid, be it in the elevator or when the plane lands.

What did you think of the Tourneur retrospective?

I think his output is wildly uneven, but a lot of his great films are pretty remarkable. I never really define myself as a cinephile. I don’t like the idea. I happen to be someone who is making movies. I am more influenced by the world around me. As I became a filmmaker, I was very curious about classic cinema. I was from the countryside, so I saw everything on TV. What was in the past speaks to me in the present. I loved Cat People, I Walked with a Zombie, and so on. What’s good about this festival is that it shows films from Tourneur that aren’t easily accessible. In the 1980s we rediscovered Douglas Sirk, which was why I was interested by melodrama, and the same thing with Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger. This was a way of reconnecting with studio work and transparencies, something that Scorsese was doing at that time. So with Tourneur I’m interested in filling in the blanks and seeing how his work connects to now.

Do you enforce an editorial perspective on the jury?

No, I don’t think so. You have to adapt to the taste, views and theories of the other members. That’s what’s hard about being head of the jury – that I like to be more irresponsible, but here I have to be the adult in the room. My job is to be able to watch movies that I would normally not be interested in, to be open and on the wavelength of the film.

Do you see a lot of similarities between your work and that of Todd Haynes, who has also referenced Douglas Sirk as an influence?

Yes, I love his work. I’m glad to have finally met him at this festival. We had dinner together and we really connected. We come from a very similar background. We are both interested in experimental, modern filmmaking. We’re both interested in using the glamour of the Hollywood melodrama. We both care for the glamour of movies. It’s what makes movies very powerful.

Which genre would you pick for a film retrospective?

I think the Hong Kong ghost stories of the 1950s, which have been completely out of reach. I’ve seen very little of them. I would also recommend a retrospective of Taiwanese cinema pre-new wave. There’s 20 years of interesting filmmaking before that. Taiwan had a history of serious, adult-oriented filmmaking.

In 1981, you wrote that filmmaking was becoming more episodic. In light of the expanded universals of Marvel, DC and Star Wars, do you still think the same?

Yes. There has been a degradation of the writing in mainstream Hollywood movies. And the audience is thought to have a five-minute memory, and anything beyond that is forgotten. It’s really strange how these movies are so sophisticated in terms of technology, and their absurd budget, but they have these miserable screenplays. They’re not even on the level of the Marvel comics – they’re sort of fascinating in their own way. How the imaginary world merges with reality, and that complexity is not in the Marvel movies. But I suppose they have to address a younger audience so some stuff is off-limits, I suspect. There’s always been a sexual dimension to those stories and characters, which is not there in the movie adaptations. The one filmmaker that is making those kinds of movies is Christopher Nolan, who I respect.

There is often the idea of doubles in your films, one real and one symbolic. How do you write these characters?

Fiction is another layer of reality. I’m interested in the way fiction sneaks into reality. I’m interested in the subconscious and the working of the subconscious. Psychoanalysis is missing in discussion of movies. But movies are always saying something about what we’re not completely aware of. That’s why in my movies you have figures who are part real and part imaginary.

Thinking about doubles, you wrote Based on a True Story, which was in Cannes this year. How did you reconcile adapting the book and Roman Polanski’s vision?

It was very difficult. To get it right you need to have full control. I liked the book for obvious reasons. Two characters: one being the projection of the other, and one being a fantasised projection. But it doesn’t make sense that way with the cast Polanski chose. It’s not the cast I would have chosen. There’s a difference of age, difference of physicality. I wrote an adaptation to suit Roman’s vision. That’s my job. I’m happy I did it. The balance between fiction and reality is Roman’s, not mine. I would have used more space for their conversations. I think there was something more complex going on. Roman likes things to go really fast and I think some of the subtleties of the book are missing. But it’s the frustrated writer talking. Part of the deal was that it was Roman’s film.

Joseph Owen

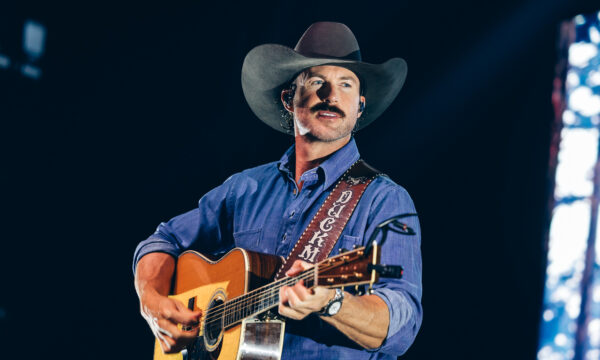

Photo: Locarno Film Festival / Massimo Pedrazzini

For further information about Locarno Film Festival 2017 visit here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS