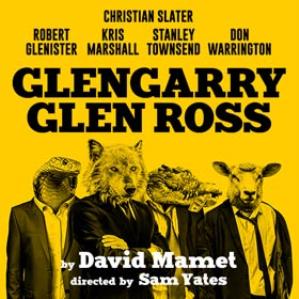

Glengarry Glen Ross at the Playhouse Theatre

Whatever contemporary relevance you want to find in the Playhouse Theatre’s Glengarry Glen Ross – it casts a timely magnifying glass on toxic masculinity; it’s a prescient example of a post-truth environment – can’t hide the fact it’s an unambitious, all-male, nearly all-white production. And yeah, yeah, yeah, these real estate salesmen so accurately reflect our aggressive, abusive patriarchy; however, that’s not enough at a time when we are crying out for unheard, marginalised voices.

Much of that could – potentially – be forgiven if Sam Yates had found a new way to make the play sing. Yet it’s not directed so much as placed on stage, done exactly as you’d expect on a pair of blandly realistic sets, with the dialogue too often lacking David Mamet’s trademark rat-a-tat-tat deliciousness.

It’s hard not to keep asking: why exactly is this on? Of course, there’s a rather obvious, Christian Slater-shaped answer to that question. Even then, the star isn’t worth the price of admission. Slick Ricky Roma should be the ultimate seducer; in Slater’s hands he just comes across as a bit of a bore, the guy you wouldn’t want to be stuck next to in the pub.

Much of the performance just feels off. Slater’s body language is ridiculous. His hilariously overdone macho manspread doesn’t exude confidence, it just looks unintentionally moronic: he is all posture and no punch. No more so is that true than in Roma’s climactic confrontation with Williamson (a limp Kris Marshall). It’s an iconic speech, an employee-on-boss dressing down that’s the stuff of workplace dreams. But in place of gradually rising fury, we get over-rehearsed bravado; the actor just can’t find Roma’s mean streak.

Stanley Townsend, on the other hand, is a delight. As sad-sack Shelley Levine he drones on and on in the opening scene; his patter is dead-eyed, spent, revealing the hollowness at its core. He’s even better when Levine returns in the second act as The Machine, swaggering and shuffling like a man reborn. Townsend is infectious in these scenes, briefly elevating Slater to his level when Levine and Roma pull a two-man hustle on a poor sap, a farcical swindle fueled by the former’s new-found confidence.

For all their bluster, these men don’t own the means of production – here the Glengarry leads; they are slaves to their bosses Mitch and Murray, their lives determined by an intermediary company man and a near-mythic scoreboard. They both are the system and are trapped in the system. Yates does nothing to dig into this seam of thought, instead content to serve up a lukewarm classic.

Roma claims near the end of the play that the salesmen are “members of a dying breed”. The thing is, they’re not, and lazy, money-grabbing productions like this will do nothing to change that.

Connor Campbell

Glengarry Glen Ross is at the Playhouse Theatre from 26th October 2017 until 3rd February 2018. Book your tickets here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS