Steve Reich’s Different Trains at the Queen Elizabeth Hall

Few modern classical composers have succeeded in having as much impact on contemporary culture as Steve Reich. The minimalist movement he pioneered has seeped into our lives through film and television scores and even pop music. Quite rightly, this celebration of the 30th anniversary of one of the composer’s most striking pieces included two works created in his influence.

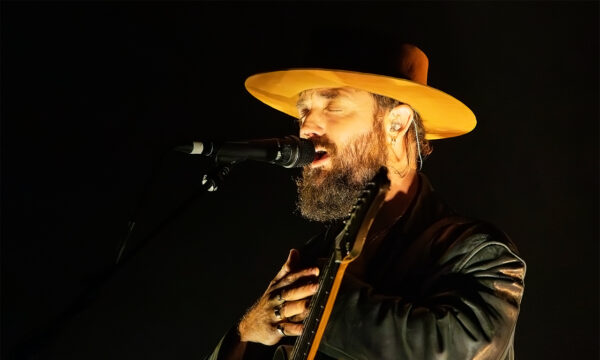

The concert opened with Bryce Dessner’s Aheym, meaning homeward in Yiddish – its accented opening chords providing a harsh jolt with the amplification of the string quartet. Dessner’s score shares much with Reich’s oeuvre, such as the use of their Jewish heritage as inspiration, and his debt to the American pioneer is clear in the music’s rhythmic pulsations. This was followed by Mica Levi’s string quartet You Belong to Me, which uses a version of the minimalist technique of sampling small sections of found material and developing them, but which takes melodic fragments from a pop ballad rather than using recordings. The London Contemporary Orchestra soloists’s playing is hypnotic and engaging, always finding a sense of direction and motion in the music. Dessner then took on the role of guitarist to perform the first Reich work of the evening. Electric Counterpoint is scored for live electric guitar and a tape of 12 other guitars, including two basses. Though it’s easy to tire of the repetitively pulsing rhythms, the piece had depth and clarity between the complex lines in Dessner’s hands, particularly in the swinging and shifting between tonal centres in the last movement.

Different Trains, the composition to which this whole evening was dedicated, formed the second half of the concert. Written for a live string quartet with tape recordings of themselves, trains and people speaking, it was also accompanied by a Bill Morrison film, mainly using archive footage. Reich moves from an evocation of his childhood in America travelling between parents on trains – using the voices of his governess and a porter – to the “different trains” he would have been on as a Jewish child if he’d lived in Europe instead. The accompanying video echoes this with footage: first of trains and railway tracks, then Jewish people being forced into carriages, and then children showing the ID numbers tattooed onto them – bringing sharply home the contrast between the emotionally ambiguous but still relatively secure first movement and the genuinely harrowing circumstances of the second. The only problem is that this then leaves the final sequence feeling a little glib and simplistic as it returns to impersonal images of railroads, whereas the music itself fuses the voices of the first two movements to create something far more reflective. Overall, though, the film is an effective addition, adding visual light to Reich’s sonic imagery.

This performance is a triumph for the newly reopened Queen Elizabeth Hall. As a cross between a retrospective and a look towards the future of classical music, there’s plenty to enjoy here. The London Contemporary Orchestra soloists are perfectly suited to this repertoire, drawing out rich colours from the shifting textures of Reich’s music, and those influenced by him.

Juliet Evans

Photos: Caspar Stevens/Southbank Centre

For further information and future events visit the London Contemporary Orchestra’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS