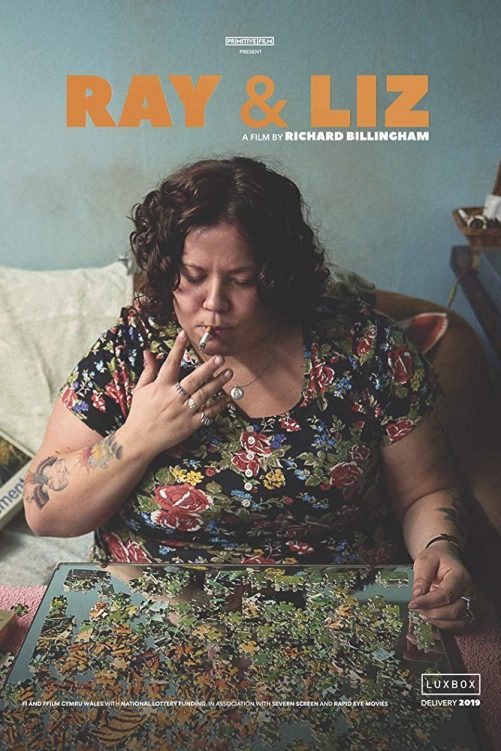

Ray & Liz

Richard Billingham’s directorial debut follows – or rather observes – the apparently stationary lives of the titular Ray and Liz over a number of decades. That the director is also a Turner Prize-nominated photographer and artist will come as no surprise to audiences. The picture, shot on 16mm film, seems ponderous, subtly capturing the exquisitely mundane.

The feature introduces the audience to an ageing Ray (Patrick Romer), who lies sleeping in his equally aged bedroom. He is encased in a palette of faded peaches and soft pinks, so old they could now be described as millennial. His dark blue jumper and haggard figure cuts across the stained saccharine florals of his environment, setting up a quiet dissonance that will continue throughout the piece.

We never see this figure leave his room; he only peeks out of the window, receiving rations of dubious homebrew and benefits from his friend Sid, and requests for money from his estranged wife Liz. The audience is soon to understand, in the first flashback, that the older Ray appears to be the intoxicated, sedated version of his overly anxious former self – played sensitively by Justin Salinger. This is the reason, we assume, for the isolated, depleted condition in which we meet him at the beginning of the film, near the end of his life.

The movie is marked by a thrumming and unsettling quietness. The sounds of the surrounding world form its soundtrack, amplifying the monotony of the day to day rather than offering audiences an escape from it. When this quiet monotony is disrupted, the impact is pronounced.

The young Liz, played to sinister effect by Ella Smith, is responsible for one of these clattering ruptures. When she finds Ray’s brother Lol (Tony Way) passed out drunk on her vomit-stained sofa – having been lured into thieving from their secret booze box – she punches the defenceless and sleeping man in the face, later turning the spiky heel of her shoe on him and battering him over the head with it. This moment is unbearable, an extraordinary reflection on the average person’s capacity for extreme violence. It is further compounded by Lol’s inability to defend himself, and the alarmed wailing of her young son Jason, who throughout the film bears witness to more than he should.

Violence of all natures sustains the picture. The violence of individuals; the daily violence of addiction, to nicotine and alcohol; the violence of the benefits system – which dictates that putting the young Jason into foster care means the already struggling family will lose £25 a week; and the subdued violence of Jason’s childish propensity to drop objects out of the window of their flat in a high-rise as his victims pass by, unsuspecting. The brutality in the feature reproduces itself; it’s both muted and overbearing, an unshakeable accompaniment to the grey existence of the film’s protagonists.

Billingham focuses in on the grotesque, converting the viewer’s gaze into one of prurience. His shots often rest on pictures in frames, animals in cages. He makes the viewer intensely aware of the function of their look, how it is converted into a gross aestheticism. By narrativising the lives of Ray and Liz he literalises their entrapment: they too are arranged and framed, cinematically and socioeconomically. And yet, despite the caution with which the film is shot, its narrative and its characters do not quite catch up with its aestheticism.

Fenja Akinde-Hummel

Ray & Liz is released in select cinemas on 8th March 2019.

Watch two exclusive clips from Ray & Liz here:

Watch the trailer for Ray & Liz here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS