“People are afraid of the power of cinema”: An interview with By the Grace of God director François Ozon

In his new film By the Grace of God, director and screenwriter François Ozon unearths the story of Bernard Preynat, the French Catholic priest who abused over 70 children in his care. Ozon tells their stories through three main protagonists, Alexandre, François and Emmanuel. We see the catastrophic effects the abuse had on the victims, and the strength they built together to form their alliance, “Lift the Burden of Silence”. During this year’s London Film Festival, we sat down with the director to speak about why he chose this subject and how he approached the filming, casting and directing process.

Your previous films, such as 8 Women and Swimming Pool, tend to focus on strong female characters. What inspired you this time to make a film with a male-centred storyline?

I’ve made so many films about strong women, I wanted to show the fragility of men. To show men expressing their sensitivity, like the women we are used to seeing in movies. I was looking for a subject, and I discovered by chance the testimonies of male victims by a priest. I was so very moved, I decided to meet them. They told me their stories and I thought their fight was so strong I decided to tell their story.

Have you ever had the urge to make a film about men before?

Well, it’s difficult – maybe because I am a man. I always felt more comfortable with women because I had more distance, I could be more lucid about the characters. With a man, I sometimes have a feeling I’m in front of myself. I can always hide behind a camera though. It’s just the need to tell a story, and sometimes the reason comes out after the release of the film. For By the Grace of God, I felt I was ready to tell this story.

How did you go about the casting process, and did you specifically try to find actors who reflected the real people whose stories you tell?

It was a big challenge to do the casting. I had the real people in mind because I met them all, and Barbarin [the Archbishop of Lyon] of course is famous in France, you can see his face on the internet! But I decided not to make them look like them. I was more looking for the feeling I had from the real person, the fragility or the strength. Like for the character of François, Denis Ménochet, I wanted someone big and jolly. It was a long process, but it was quite interesting to find the right person for each character.

Did you ever let them meet the victims?

No, and they didn’t want to, because for them, it was a screen, it was a fiction. The victims were not famous, not like if you make a biopic of Elton John. Nobody knew these people, unless you explore their interviews on the internet. The actors wanted to create new characters. They met after the premiere of the film.

Was it a difficult pitch to the actors to say, “We’re going to look at this, this is the subject matter”?

It was a big responsibility for everybody, but the fight was fair, and everyone was so involved in the process of the film. Everybody was nervous at the premiere. The victims were nervous to see the reactions of their families, the actors were afraid they might have betrayed them, but everything was ok. The fact it was fiction was easier – if it was a documentary it would have been very hard for the victims.

Did you have any obstacles to overcome whilst filming, given the subject matter – constraints from the church or within the town of Lyon?

We took a huge decision to shoot the film in secret. We didn’t give the real title, we said the film was called “Alexandre”, because if I had said “By the Grace of God” everyone in France would have known it was about “Affaire Barbarin” – you have seen that that’s what he said in the film. So I lied about the title, the synopsis was just a meeting between two 14-year-old friends, and I was then free to do as I liked.

The exteriors were all shot in Lyon. We shot the Basilica, which belongs to Cardinal Barbarin, so we just said: “We’re shooting for tourists.” All the interiors were shot in Paris. However, when the trailer came out with the real title, By the Grace of God, suddenly they realised, and it became quite difficult for us. The church, the lawyer of the priest, all tried to stop it, but after a few trials we won and the film was released. But there’s no scoop in the film, it’s all in the press. You see how people are afraid of the power of fiction, of cinema, more than a magazine article – they can attack it. After the release, we realised the power of the film’s success, as the priest was defrocked just afterwards.

The phrase “By the grace of God,” which Barbarin uses – was that always the title for you?

It was obvious, actually, it’s a beautiful title, thank you Cardinal Barbarin for that! But after he says this phrase, it’s like a knife in the heart for the victims. Afterwards, he apologies, saying it’s a mistake, perhaps a Freudian slip.

It’s interesting how the three protagonists say they are not against the church, they are pro-church, their fight is for the church.

That is why Catholics love the film and came to see it, because one of the lead characters is very Catholic. He believes in the institution, then he decides to go for justice, then there is an investigation and they discover more victims.

Regine Maire, the elderly volunteer from the Diocese of Lyon, organises the initial meeting between Alexandre and Father Preynat. Especially notable, in the scene she joins their hands to say the Lord’s prayer. Was this a true representation of the role she played?

Yes this is amazing. It’s true. I asked Alexandre: “Did it really happen like that? Did you really give your hand? Why did you do that and was it to beg for forgiveness?” What was important for him was actually to hear Preynat saying, “I’ve raped you.” In front of someone important in the church.

Alexandre was very happy after that because he was sure Barbarin would act after knowing the facts. He thought Barbarin was honest, that he didn’t know. Now there was proof from the priest in front of him saying he remembers everything he did to Alexandre as a child. I don’t think Alexandre realised that making the prayer with the priest was going to be so shocking for us. It’s interesting to see how the Catholic church uses the concept of forgiveness to manipulate.

The film’s made up of three stories, it gives a nice building of weight that escalates throughout the film. Was it always the plan to have multiple characters?

It’s the reality. First Alexandre was alone, he began the fight alone. He didn’t know there were other victims. Very often when you are an abused child you think you are alone, but step by step you realise there are other victims and you begin to share your voice together to become stronger. The structure of the film is like a relay race between three different characters. Alexandre alone decides to seek justice, then there is an investigation, then we discover François. For the third character it was more complex – I had the choice of more than 70 other victims. So I asked them to help me find someone, not coming from the same bourgeois background, maybe someone without a family or a job. They told me, you have to meet Emmanuel. It was very touching as his life was very destroyed, and the creation of their Association was like a new life for him.

Was it hard to remain true to the entire story? Were there moments you wanted to add your own take on things?

No, it was not to add, it was more to take stuff away. I had so much material when I had met all the families and victims. I had so many things that I could have made the film about five hours long. I realised the reality was more important than the fiction I could provide. For example when I met Alexandre’s wife and she told me she was raped as a young teenager too. If I had made that up in my script people would have said: “it’s too much!”

Did you have to cut down the three stories to squeeze them into your run time?

No, it was more that I could have developed more things around them, with the families. I could have made one long feature just focusing on Alexandre, but I decided to give all three characters time.

Did you direct differently with each character?

Yes, of course, because they are on different journeys and have different interactions. They each had very strong paths and were very involved. The art of the actor is to work on dissociation. You realise that when you were abused as a child and you didn’t understand, you use a kind of protection. There is a link in this with their acting for the film.

Did you feel emotionally invested in the story as you uncovered more things? Did you find it traumatic yourself just hearing all these stories?

Of course, and you know I had a Catholic education! One day I had a memory of something that happened to me when I was about eight years old. I was playing the game hide and seek, and a priest I really liked said: “Come, I have a really good hiding place,” and he was blocking me and breathing so hard. This priest was fighting against his repressed lust. And all I was thinking was: “Oh my God, they will find us, because he’s making so much noise.” Finally someone, a kid, shouted: “It’s over,” and I ran away. Listening to the victims, I remembered this scene. If this priest had crossed the line, what would have happened to my life too?

Parents today talk to their children, they know their bodies are theirs, they know the dangers. The flashbacks in the film are very important. They show that the children don’t understand what is happening to them. Like lambs heading to the wolves.

How do you move onto another project, given the intensity of this one?

I needed something light. It’s a coming-of-age movie, about teenagers. A beautiful love story, during the summer, it’s like a holiday after this.

Thank you very much for speaking with us.

Ezelle Alblas

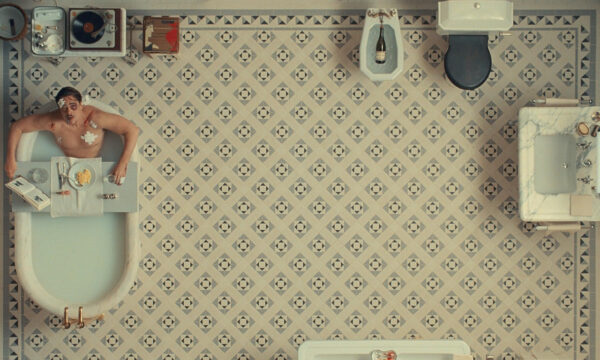

Photo: Jean-Claude Moireau

By the Grace of God is released nationwide and on Curzon Home Cinema on 25th October 2019. Read our review of the movie here.

Watch the trailer for By the Grace of God here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS