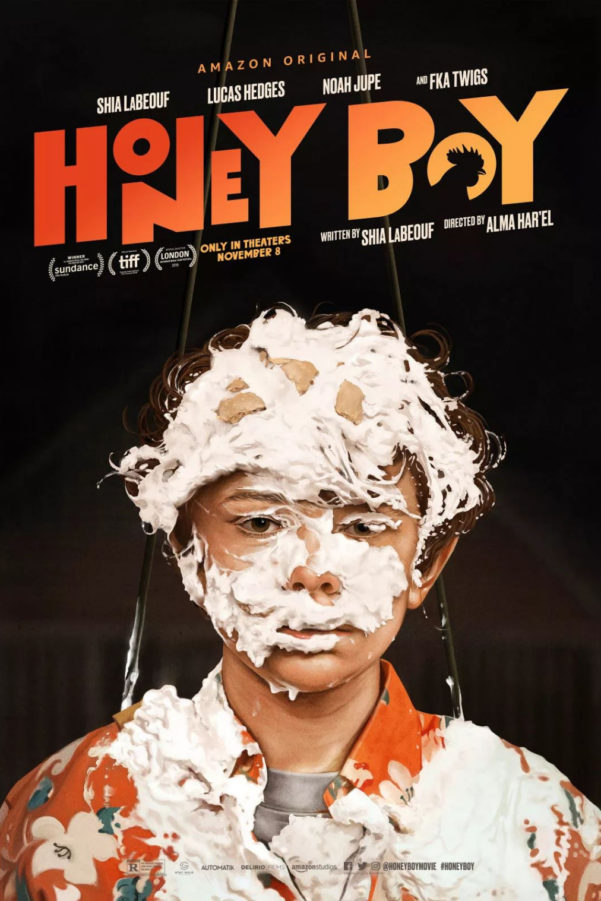

Honey Boy

Welcome to the Shia LaBeouf show. It feels like the 33-year-old has been with us forever, and for millennials, his rise through Even Stevens, young adulthood as Spielberg’s golden boy in the Transformers franchise, and maturation in roles for Andrea Arnold and Lars Von Trier, has mirrored their own ageing. All the while, he has responded to the spotlight with public outbursts: either getting in trouble for drink and drugs, or participating in a bizarre performance art he calls “meta-modernism” – an Andy Kaufmann rip-off by way of James Franco.

And now, in Honey Boy, the actor finally lets us deep inside his soul with a barely fictionalised account of his relationship with his father during his years as a TV star. Played by LaBeouf himself, the part-time clown and full-time abusive dad torments his son (Noah Jupe), who he calls Honey Boy, through narcissism, backwards life advice, rampant misogyny, and neediness. It’s an impressively mannered performance from LaBeouf, whose physical tics and throwaway jokes are clearly observed behaviour. This is made literal in a scene when Honey Boy translates one of his father’s rants down the phone to his mother, watching his dad and then mimicking him, spot on.

Inherited trauma is the film’s main focal point. Scenes set in rehab show an older Honey Boy played by Lucas Hedges, whose high-energy performance style lends itself well to a pastiche of the LaBeouf persona. He searches for release from the pain delivered by his father, and indeed, the screenplay was apparently written while LaBeouf was holed up in rehab – you even see parts of it being performed within the film here. Alma Har’el, the Israeli documentarian who has long run with Shia’s metamodernist crew, leaps into (semi)fiction filmmaking here. If the visual style is undeveloped, a collection of handheld indie tropes and magic-hour colours, it’s because each scene is firmly in service of the story and characters.

Occasional detours with FKA Twigs as a neighbour with whom Honey Boy has a flirtation don’t entirely work. Twigs silently dances in the moonlight like a Fellini Madonna-figure, but the film doesn’t gesture one way or the other about the extent of Honey Boy’s deflowering. The saccharine presentation of their intimate moments, which always hold back from overtly sexualising either of the characters, blurs the point of this sub-plot. Maybe the relationship is a ray of hope for Honey Boy, who doesn’t interact with another child once in the film. Maybe it is an abusive relationship. Perhaps it is both, but the film’s insistence on poeticising Twigs’ wordless body doesn’t cue the viewer.

Honey Boy is funny, sweet and sincere, but sometimes it can be difficult to take LaBeouf at face value. If we are supposed to believe this as a burst of honesty rather than an act of mythmaking, then the vagueness of the filmmaking makes it difficult to parse. Even when it is painful to watch someone else’s therapy, Honey Boy is a cathartic cine-memoir.

B.P. Flanagan

Honey Boy is released in select cinemas on 6th December 2019.

Watch the trailer for Honey Boy here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS