Steve McQueen at Tate Modern

No director has ever won an Oscar without being able to create strong emotions in an audience. Let’s assume that this is also Steve McQueen’s aim in the world of art – for which he won the Turner Prize in 1999.

So, what would McQueen, who scooped that prize along with Academy Award for Best Picture for 12 Years a Slave in 2014, have us walk out of the Tate Modern feeling after watching his video and film installations? And, do we feel?

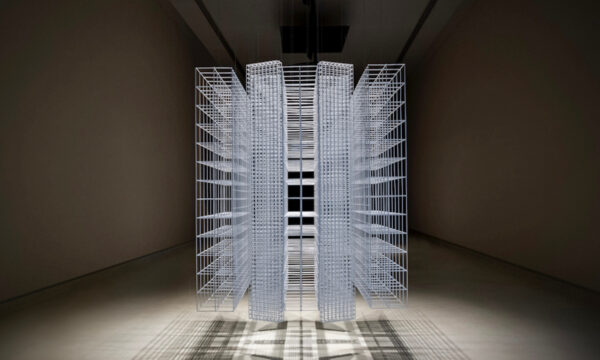

We are welcomed (if that is the correct word) into the open, dark space by Static (2009) – a video of the Statue of Liberty shot from a helicopter. The sound of chopping blades fills the room. McQueen said he wanted to be “irritating the statue like a fly.”

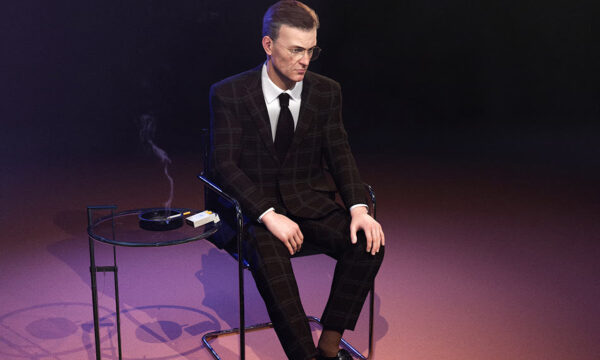

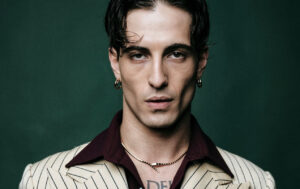

In Girls, Tricky (2001), the musician vibrates with apparent rage in a studio, as he rehearses the pain of being a fatherless child for his album.

Charlotte (2004) is a Super 8, drenched in red light, of the artist bringing the tip of his finger nearer and nearer to the eye of cult actress Charlotte Rampling. Unblinkingly, she accepts the looming digit until he touches her eyeball. But she is a trained professional; we are more vulnerable to what McQueen shows us.

There is enough – just – for pleasure-seekers. But the sheer visual joy of Ashes (2002-2015), a long shot of a beautiful male fisherman bobbing on the end of an orange boat in front of a Grenadian sky, is punctured by the sound of chiselling. On the flip side, there’s a video of a stonemason carving Ashes’ name on his grave. He had been killed by drug dealers after unearthing a stash.

We enjoy the muted colours of helmets and uniforms over a sparkling underground river in Western Deep (2002). But we are also looking at workers in the world’s deepest mines: the TauTona near Johannesburg. We can’t fully appreciate the fizzing pinks, purples and blues of a twisted white sheet shot in low light found in Illuminer (2001) because the soundtrack is a French news report about the US Marines being trained to go to Afghanistan. And it gets under the skin, this mixture of fascination, apparent simplicity and discomfort. The feeling of being haunted – but not quite by beauty or sadness – stays with us.

In 7th Nov (2001), McQueen’s cousin Marcus (accompanied by a still of the top of his head which could be taken in a morgue) talks about how he can’t picture all the blood released when he accidentally shot his brother dead because it would “send him doolally”.

McQueen has no such concerns in creating images that haunt, taunt and unsettle, while somehow being simultaneously entirely ordinary.

Michael Willoughby

Featured image: Steve McQueen, 2009. Image courtesy of Thomas Dane Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery (Steve McQueen)

Steve McQueen is at Tate Modern from 13th February until 11th May 2020. For further information visit the exhibition’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS