“The ‘art in isolation’ we’ve been seeing is mostly soul-destroying”: An interview with Bill Bankes-Jones, director of Tête à Tête Opera Company

This year’s Tête à Tête Opera Festival is facing a particularly daunting challenge: how do you organise it with the heavy impact of the pandemic? Even with lockdown restrictions lifted, many challenges need to be overcome – but it’s looking as promising as ever. Bill Bankes-Jones, Director of Tête à Tête Opera Company, has offered us an exclusive interview to discuss the festival and the issues they have had to confront.

Hi, thank you for your time. This year’s Tête à Tête Opera Festival is exploring the themes of unreal and fictional worlds, impending political doom, and apocalyptic futures to reflect a real world in a state of unease. How did the idea for this focus come about?

The festival functions in many ways like an Edinburgh Fringe for opera. Companies are a lot better supported (e.g. they don’t have to pay to take part) and a tiny bit more regulated, but not much. Each year, as a result, the Festival reflects what is really uppermost in people’s minds and hearts. In previous years there have been fascinating tendencies; a year of mental health issues, another obsessed by isolation and insularity (driven, I think, by Trump and Brexit). The beauty is that artists are thinking: “what really matters now?”, rather than: “what am I going to be caring about in four years’ time?”, as they’d have to in a conventional opera house.

What are some of the highlights of this year’s festival?

A fantastic question, as we don’t really yet know what will actually happen. I never like singling out shows, as I think the joy is the experience of dipping your toe in and experiencing maybe three different worlds in the one evening. You wouldn’t look through a kaleidoscope only in order to see the red bits; come to us to enjoy the full spectrum of what artists are presenting!

Aside from the thematic guidance, are there any guidelines or restrictions in form, length, etc. that the artists are asked to adhere to?

In a normal year, I’d try to program three different shows in one evening, together with, maybe, a tiny happening or two in the foyer. That therefore sets its own length restriction – 30-45 minutes is optimal. I also think new opera is best digested in short bursts. It can be really grim to be stuck in a big opera house with a single new work that you are not enjoying as it enters its fourth hour. Other than that, the more variety, the better.

How and when was the Tête à Tête Opera Company founded and when did the first festival take place?

Tête à Tête’s first show was The Flying Fox, in 1998. I had left ENO as a staff director after five amazing years, partly because I was keen to do a lot of things that couldn’t happen there. I met a colleague one evening who told me she was planning a show featuring live dolphins. I wanted to meet whoever was letting her do this, so I wrote a letter (it was that long ago) to Tom Morris, who was running BAC. Unprecedentedly, he rang me the next day asking if I’d come and see him the following morning. He asked me what I wanted to do. I was in the middle of rehearsing Die Fledermaus at the Royal College of Music, so I improvised and said I wanted to do that in a tiny studio, in a very traditional production, but to remove the audience’s chairs in the middle act (the party) so that it really was a party. Amazingly, we were sponsored with a huge amount of Austrian sparkling wine – the audience averaged a bottle each after their interval drink and ended up dancing and singing with each other. One of the most joyous shows ever. Really hard to imagine now.

The first festival took place in 2007, partly when we were dropped by ACE and had no funding, so I thought: do a load more work, and partly out of a sense of wanting to plough back in some of the help we had had from people like Tom Morris. (We are very happy to be back in the ACE fold again now).

The coronavirus lockdown has required many artists to come up with novel ways of presenting theatre and opera online. What are some of the most interesting approaches to this issue you’ve witnessed?

I set this out in my Manifesto. I wrote this after the initial Covid-19 paralysis in March as a device to give us the foundations for a festival wherever it might be. It’s all about how the performing arts are really compromised online, as you lose all the human interaction between performers, and audiences and performers. There are so many inputs and complications; the intricacy is, above all, what makes it fascinating. I find the “art in isolation” work we have been seeing mainly soul-destroying, and more about the performers’ needs than any real human connection. It’s heartbreaking.

By far the most interesting work, I think, has been rising to the challenge of how to reach the 12,000,000 people who have no access to the internet. I was very inspired by Stella Duffy’s Tiny Revolutions for her Fun Palaces, a provocation to reach these people which we talked about a lot with our artists when in full lockdown. Lots of ideas came out, about sharing postcards, singing down the phone, telling people your story through messages in food boxes, all sorts of things. These felt like the real connections we were missing to me far more than musicians accompanying recordings of each other in bedrooms online.

We have been talking to each other so much, and something I think we’ve agreed among all the artists is that any works that do have to end up online need to be made by at least some artists who are together, and also with live people reacting, together with the artists, giving them the feedback they get from audiences in real time and space.

Did lockdown present any particular challenges when organising this year’s festival?

Oh my God, yes, and it’s not over yet. I feel like a polar bear with each limb standing on a separate piece of ice, each moving independently. Everything shifts every day. We only found out yesterday that any kind of performance to the public at all is allowed now, and that’s only out of doors. I’ve just before this put a proposal in to the DCMS to become one of their pilot projects for return to professional performance. And if there’s any resurgence of infections, we may well be back to square one again. I have done so much work in such crazy circumstances that it’s not unfamiliar to me to have to build around uncertainties, but I don’t think anyone has had to deal with uncertainty like this before.

What impact do you believe the festival will have on the world during the coronavirus crisis, and on the world of arts in particular?

It’s hard to say until it has happened and we know what it is. But I am really pleased not to have given up and mothballed, to keep conversation going with artists and treat them as artists, rather than unwanted freelancers. It has felt really important to keep some hope going. I’m also very glad to have been working with a venue, The Cockpit, that shares this attitude. Performing is part of who we are, as well as how we earn our livings. So many performing arts freelancers have been left high and dry with no work and no income. If you take what you live for away, as well as how you live, really what is left?

What will the festival teach us about how to respond to the coronavirus?

Again, I can’t answer what something that hasn’t happened yet will have done. We are all learning an awful lot and, though I’d rather things were not as they are, there is still a thrill.

Do you think the virus will have a lasting impact on the way we perceive and engage with opera or theatre in general?

Oh God, yes. The one thing that was obvious from the start was that we will never go back to where we were. I’m at the centre of a lot of webs, so hearing and seeing a lot. It feels like hardly anyone has understood the extent of the damage to our sector. Even with the very welcome £1.57bn government bailout, it’s still very obvious that some institutions we take for granted will go. It will take a very long time indeed for us to be able to make theatre as we did before, with that level of intimacy, packed houses, human interaction with the audience. And the freelancers who make up 70% of the workforce really have gone through the wringer. By losing contracts and falling through the gaps in government schemes, 36% of us haven’t received any income, financial support, or anything since March. People talk about decimation without quite knowing what it means. It’s annihilation. I am really proud to be part of #freelancersmaketheatrework and fighting this corner on behalf of festival artists and all freelancers, but it is one hell of a fight.

What steps are you taking towards your vision of worldwide community-building in opera, especially considering it is seen by some as being elitist?

Huge question! Opera has been splitting in two, one part increasingly grand and luxuriant, the other more and more dirty and cheap. I’m spearheading the latter. And reaching all over the world. Everything we have hosted or produced for more than a decade has been posted online in archive video form (so a record of a performance rather than an alternative to attending a performance). The uptake has been huge, worldwide – we passed a million views a long time ago. We’ve also made a YouTube channel, #mynewopera, where anyone is welcome to contribute work as well as to consume. We’re miles ahead of the curve, though, in terms of securing rights, and the confidence of our artists to have their work distributed in this way, though, so the rest of the world has a lot of catching up to do!

Thank you so much for your time!

Michael Higgs

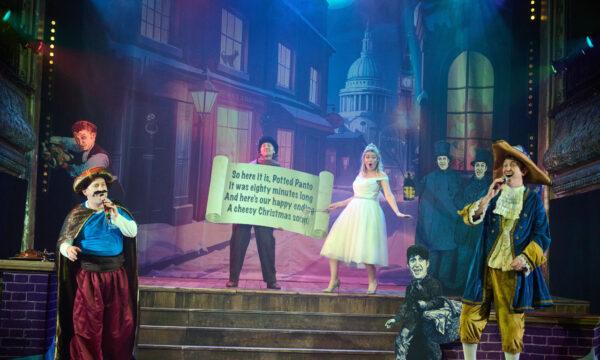

Photo: Hugo Glendinning

For further information about the Tête à Tête Opera Festival visit the company’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS