Roger Michell and Jim Broadbent present The Duke at Venice Film Festival press conference

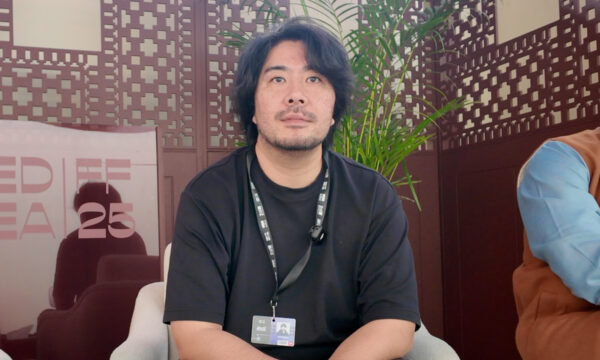

The Duke is the incredible story of Kempton Bunton, a 60-year-old taxi driver from New Castle who, in 1961, stole Goya’s portrait of the Duke of Wellington from the National Gallery in London. It was the first (and remains the only) theft in the gallery’s history. Bunton was a social activist who had long campaigned for pensioners to receive free television; he used the painting to send ransom notes saying that he would return it on condition that the government invested more in care for the elderly. Director Roger Michell, lead actor Jim Broadbent and producer Nicky Bentham presented the feature at the Venice Film Festival press conference today.

How did you end up working on this project?

Nicky Bentham: Six years ago I got a random email in my inbox from Christopher Bunton, the grandson of Kempton, who had this amazing story in his family. He sent me a short paragraph summing up the story and I was like: wow, I never heard something like this before. I did some research and I found out that what he said was true. His grandfather and father held an archive with all this material and I jumped on the chance to be able to tell the story. I was very delighted when Roger joined me on this journey last year.

Roger Michell: It’s a story that’s not very well known in England even though at the time it was a notorious case, the first and only time painting was stolen from the national gallery. This a strange, very English, eccentric story. This eccentricity attracted me to it. And working with Jim.

Jim Broadbent: I heard about this story and the possibility of getting the role quite early on. My agent told me about it and I found out it was a delightful story. And working with Roger again!

It’s strange for someone to commit a crime for the greater good. It’s a sort of radical idealism, the dreams of this man who fights for the good of the society.

RM: In a way, it’s a Robin Hood story. Robin Hood is referenced in several ways. He isn’t Robin Hood, but what’s great about it is that, as in many pieces of English fiction, it’s a story about a small man, a working-class man from the north of England, disenfranchised, jobless. At Ealing Studios in the 60s, it continues to be part of English culture, this celebration of eccentric individuals. His is a revolutionary act.

JB: It’s an incredibly compelling character; he’s a real troublemaker and doesn’t only think of what would make his life better but the community and the wider world.

RM: His character wants to be a great playwright, like Cechov, and he’s fairly rough in many ways: we never see him doing the washing up or helping the wife with any work; he’s happy for her to win the bread for the household; he gets sacked all the time. He’s really irresponsible in terms of family life. But he has this caring side, he’s very kind and wants to help the community. There’s a balance between positive and negative sides. This helps the public understand he is a real person, not just an idealised version.

You said that the films produced in Ealing inspired you?

RM: I was inspired, in terms of imagery, by other British films made in 1961. A whole generation of new directors working in black and white in the north of England, talking for the first time about the working class in the north. Unemployment, industrial waste.

Why do they talk about the thieves as potentially being Italians? Is it true? Is it a reference to the Louvre? Or is it a joke?

NB: It is a bit of a reference to the Louvre. The real date of the theft of the Goya it was the anniversary of the Louvre theft, which was just a coincidence really. But all the police and Scotland Yard thought that this was relevant. And they also thought it was an organised gang, not a man from Newcastle.

RM: Yet another example of racism.

JB: And the fact Scotland Yard gets it wrong.

How did you approach this considering the current political climate in the UK? There was already a Radio 4 drama, right?

NB: It was a radio play for the BBC, yes. But not a drama written with the full story of the family. This is the first time the family have opened their archive. When we approached the writing with our writers we thought there was a lot of relevance to today’s world. People living in isolation but connected by the internet. And then Brexit, too. The help of one person relies on the help of the whole community. For all of us, it kind of grew in relevance and importance. We thought from the beginning that it had a very special message.

How do you feel about the fact that the BBC still has a mandatory licence fee?

RM: I think the BBC is a great rainforest so I defend the BBC.

Isn’t “the common good” a bit of an excuse for the protagonist? Isn’t it a triumph of the politically incorrect? Is this the idea too?

JB: I think he’s certainly an unusual protagonist. The fact he’s actually… well he didn’t actually do the robbery. But he was prepared to back up his son. It is very much illegal [what he did]. It’s risky stuff. But it makes for a great character to play.

Why did you show Munch’s The Scream behind the Goya? That painting was stolen on several different occasions. Was it a reference or a funny moment?

RM: Yes, it’s intended to be a funny moment.

To what extent have events been dramatised?

RM: As far as I know, the bakery shop wasn’t documented. In principle, the events of the story are true, although they have been compressed – in real life, it took four years.

NB: Actually, the bakery scene is rooted in truth. Kempton did lose his job many times; once he stood up for an Asian employee whose wages had been docked. It just didn’t happen in the exact way we see it in the film.

The trial was really a moment where the man had a proper stage to talk, something he had always looked for.

JB: For Kempton, making his points in a public way, against the establishment, was a dream come true! He wanted to make the most of it.

RM: I remember the day we shot the scene, with all the crew and extras, it would have been great on the big screen.

NB: That was a brilliant moment. We did use the original court transcripts that we got from the national archive. The writers used some of the real words and defence for that scene. It was partly due to the brilliance of Jeremy Hutchinson, played by Matthew Goode, who mounted this very very clever defence. He cleverly used Kempton’s performance to win over the jury.

How do you feel about being about in Venice? And how will you feel about restrictions for older actors?

JB: I’m absolutely thrilled to be in Venice. Coming here we were all apprehensive about the risks involved. But it’s so wonderful that Venice is presenting a festival this year; it’s the only one so far. It’s heartwarming and exciting. It feels almost normal, which is a great thing. The pandemic is taking a lot of liberties from older actors. It will unfold in due course. It’s worrying for now.

This is also a family drama: it talks about a tragedy that the family hasn’t moved on from. Was this faithful too?

NB: It’s true that the family were overwhelmed with grief having lost their eldest daughter. The picture in the film is the actual picture of her. It’s been a shadow on the family for a very long time. It’s possibly not entirely true that these events have healed the grief. The whole process did some healing. At the time it was quite embarrassing for the family to be part of this story.

Can you tell us a bit about the locations you chose?

RM: Bradford is such an extraordinary city, so full of potential. Moving to Leeds was like moving to New York. We wanted to film in Newcastle but it wasn’t possible.

Filippo L’Astorina

Photos: Filippo l’Astorina

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS