Sin: The Art of Transgression at the National Gallery

Tucked away in the ground floor of the National Gallery is a small exhibition devoted to one of the most potent concepts in Western culture: sin. It contains just fourteen artworks in two small rooms, but they have been chosen for maximum impact. Tracey Emin’s neon piece It Was Just a Kiss X has been mischievously placed next to Bronzino’s An Allegory with Venus and Cupid, a work that so scandalised Victorian sensibilities that parts of it were painted over (tongue in mouth and erect nipple since restored to their original lasciviousness). The painting depicts an incestuous kiss between the mother and son from Roman myth. It is a densely symbolic work, composed for both titillation and revulsion – themes also prominent in Emin’s work. The show pony of oversharing, she has made a career of sticking two fingers up at the concept of “sin.” The striking pink neon message taunts patriarchal society and is punctuated with an unrepentant, scathing X. Is she telling a lover to chill out about her “cheating” or a prospective lover to manage his expectations?

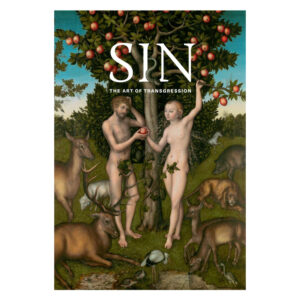

There are, naturally, several depictions of Adam and Eve committing the Original Sin. In Lucas Cranach the Elder’s 1526 version, Eve is a wily vixen, all solicitous expression and artifice, while poor, naïve Adam scratches his head with doubt. The message is so blunt that you might think this is a lampooning of patriarchal attitudes, but given its date it is most likely reinforcing them: women are inherently cruel and wont to lead men astray – except, naturally, the Virgin Mary, who is depicted forcefully in Diego Velazquez’s The Immaculate Conception. This painting has a mysterious, hypnotic quality; the woman chosen by God to be alone among humans in her lack of sin stands atop a translucent moon, in front of the sun, which shines around her cloaks, and with twelve stars around her head. Through the moon, one can see symbols of immaculate purity: a garden, a temple, a fountain and a ship.

There is a William Hogarth, depicting a slothful young married couple. He slumps in a chair with an unmistakable black mark of syphilis on his neck, while his dog sniffs at the mistress’s hat in his hand. She reclines with a smug expression, a proud clutch on a mirror. A violin, playing cards and books lie abandoned on the floor as a man leaves in exasperation clutching a ledger brimming with bills. The message seems clear: sin doesn’t pay.

Youth, a mixed media sculpture by Ron Mueck of a young man examining a large stab wound in his torso with a look of surprised detachment, is uncomfortably lifelike, from the texture of his skin to the tendons in his hands. It is a thought provoking piece. Is he a modern Christ figure or a scapegoat?

The greatest masterpiece in this collection is also its most diminutive. The Garden of Eden by Jan Breughel the Elder (1618, oil on copper, on loan from a private collection in Hong Kong) is a small, impossibly detailed scene. In the foreground is the abundant glorious fauna of paradise: a pair of snarling lions, a haunted looking horse, a glamorous peacock, even a monkey entertaining a half-seen porcupine in one corner. However, in the distance is a glimpse of destruction. Adam and Eve (here looking more like co-conspirators although it is still Eve reaching for the forbidden fruit) are in the act of their own ruination. The composition is startling.

The theme of Sin is so interesting that it could stand to encompass more contemporary work. What is there, however, chosen by Dr Joost Joustra, is thoughtful and profound.

Jessica Wall

Sin: The Art of Transgression is at the National Gallery from 7th October until 3rd January 2021. For further information visit the exhibition’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS