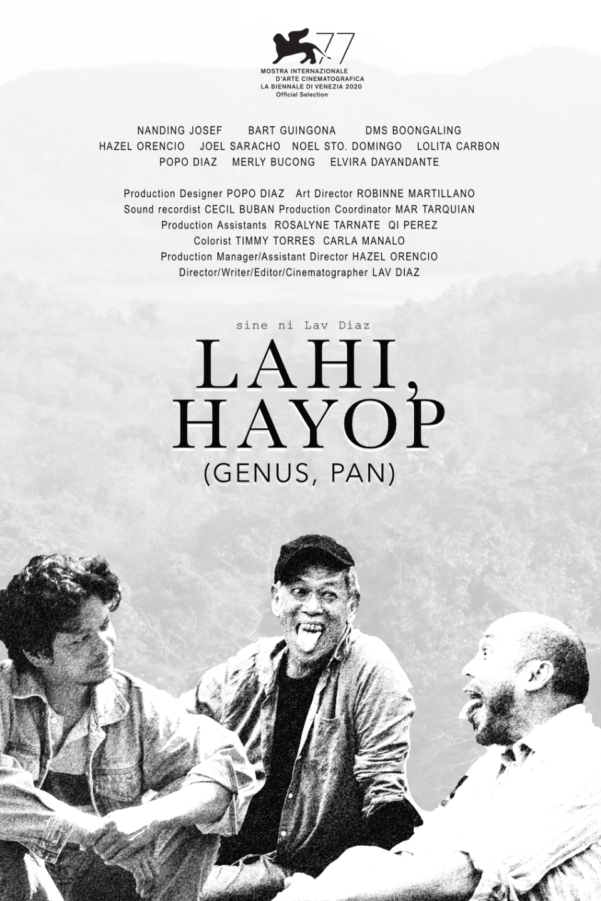

Genus Pan (Lahi, Hayop)

Lav Diaz makes long, slow films. The first point is difficult to dispute while the second functions as a sort of journalistic shorthand. “Slow cinema” usually describes unfurling cinematic illustrations that ignore or withhold traditional conventions of narrative and plot. It has a simple categorical purpose, which dubiously brings Diaz’s works into conversation with such diverse filmmakers as Tsai Ming-liang and Kelly Reichardt, whose most recent efforts found many admirers at this year’s Berlinale.

Yet considering slowness as a critical idiom is not without merit. For Diaz, particularly, it inscribes a certain type of material life in the contemporary age. His focus shifts from those caught within the pincers of modernity to those on the periphery, often in poverty. A Filipino director committed to depicting the rural undulations of his homeland, he presents his fictions as quasi-ethnography, daring viewers to elicit truth and meaning from his careful tableaux.

By Diaz’s standards, his newest feature Genus Pan is short, clocking in at a relatively spry 150 minutes. It is a story about three men (Paulo, Baldo, and Andres) who live in a small community. Their relationships appear mainly determined by debt and obligation: who owes money to whom; the metaphysical nature of transactions (“A deal is a deal.”); and the frustrations wrung from intimate, small-scale commerce. While traipsing through the woodland, the men resort to bickering and minor scuffles. Diaz frames their interactions with studied simplicity. The earth beneath and the trees around them take on an omnipresent tactile quality, beckoning the trio towards genesis and their ancestral states.

The sound design (and its integrity to the action) is intuitive. Oral traditions and indigenous songs act as audio checkpoints. One scene with a radio insinuates a broader political message. Talk on the airwaves of fascists and demagogues provides an admirably direct allusion to the country’s incumbent president, Rodrigo Duterte. Hidden creatures offer both an oppressive soundscape and distant imagery. Gecko calls punctuate the ramshackle journey and “the black horse” endures as an apparently imagined totem of the forest. Diaz has stated his intention here is to show “man honestly acting [as] an animal, as he has been acting […] all his life.” Man descended from chimps; the residue lingers. Women are a bit of an afterthought, victims of male aggression, a silent presence on the other side of leaves.

These deliberately bestial evocations, and their proximity to human psychology, emerge fairly well realised. Diaz inserts enough ironies in his characterisations to undercut the squawking chamber-piece disputes and subsequently neat thematic readings. Protrusions of violence upset any dwelling in the pastoral. Incongruities, such as a figure kneeling in devoted Christian prayer while dressed in a modest polo shirt, speckle the unbroken stream of canvases that constitute the film. Diaz thus renders creaturely life as a semi-spontaneous mixture of splatters, blots and mottles, all contained within the formal order of the frame.

Joseph Owen

Genus Pan (Lahi, Hayop) does not have a UK release date yet.

Read more reviews and interviews from our London Film Festival 2020 coverage here.

For further information about the festival visit the official BFI website here.

Watch the trailer for Genus Pan (Lahi, Hayop) here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS