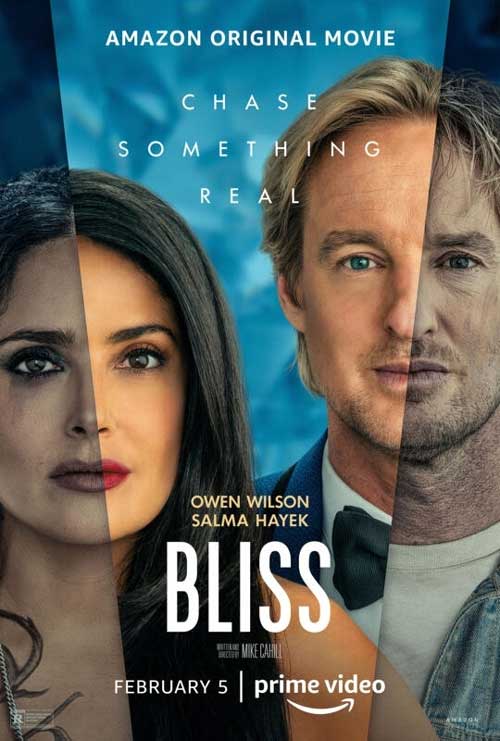

Bliss

Bliss is a po-faced and dramatically inert science fiction meander that remains firmly committed to the vague exploration of “ideas”, but at the expense of joy, narrative and image-making. Writer-director Mike Cahill is admirably concerned with the permutations of his premise: that there exist two worlds, either of which is real or unreal, promising a suggestive and ambiguous tale. But here, cerebral considerations are expressed without visual intrigue or a sense of cinematic wonder, exemplified by the use of colour grading. The purportedly dystopian day-to-day is rendered in tedious greyscale and the alternate celestial super-civilisation in iridescent, oversaturated yellows. A will-this-do? approach to sound and vision pervades throughout.

Greg (Owen Wilson) is a distracted, prescription-addled worker bee in a company called Technical Difficulties, a name that functions as a supposedly wry nod to the devitalised mundanity of modern human experience. This existence is articulated through invasive sound design consisting of harsh rings, outside traffic, brusque tones and abrupt interruptions. The proximate camerawork tells viewers that Greg’s life is indeed a suffocating one: he’s staying in a motel, separated from his wife and estranged from his children. His major problem seems to be vocalising his thoughts, a fact that is handily emphasised by echoed lines of dialogue about the impenetrability of his mind. In snatched moments at the office, he draws designs of an idyllic landscape, a dream of home.

After an arbitrary act of violence (a technique upon which the film heavily relies), Greg must seek help from a half-baked bohemian figure called Isabel (Salma Hayek). It’s unfortunate that Hayek is cast as the exoticised, woozy figment; this performance reinterprets her dubious role in Sally Potter’s equally derisory mind-bender The Roads Not Taken (2020). While Wilson plays to type as the dumbfounded everyman (a stand-in for the audience), Isabel is written as the thankless expositor of the film’s mysteries, most of which are impossible to care about. As the arcane plot points jumble, often presented through baffling clips of TV news coverage, emotional investment is perpetually assumed rather than earned. The archetypal lost daughter, in whom the audience’s sympathies presumably reside, is discarded and reintroduced with laughable consistency.

Cahill invokes some pleasant visual tricks to indicate the relative artifice of each world – cheerful lo-fi holograms and flickering background silhouettes – but the cinematic grammar, particularly the inelegant editing, tends to the guileless and perplexing. In fairness, many of the film’s aesthetic choices could be plausibly justified by its conceit (it watches like a stilted video game because maybe it is one!), but this fails to excuse the accumulated irritations: the toilet cubicle as a liminal space; the ham-fisted ecological metaphors; the constant allusions to illusions; the indifferent gestures to literature on simulacra; and, most strikingly, the cursory deployment of public intellectuals Bill Nye and Slavoj Žižek. These pretensions of philosophical inquiry provide the primary source of agitation. For a more entertaining account of how civilisation dilutes and deadens people, its audience is better off reading Brave New World or the collected works of Rousseau.

Joseph Owen

Bliss is released digitally on demand on 5th February 2021.

Watch the trailer for Bliss here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS