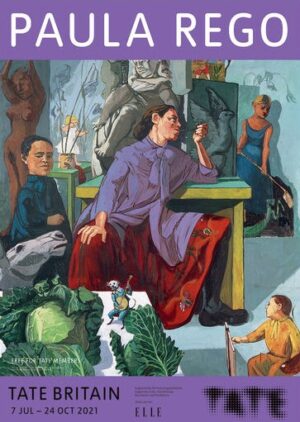

Paula Rego at Tate Britain

With her dramatic, intense imagery and superb draughtsmanship, the Portuguese-born, London-based Paula Rego has been acclaimed for redefining figurative art both in the UK and internationally. The major retrospective of her seven-decade-long career now at Tate Britain draws attention to the personal nature of much of her work and its social-political context. It features over 100 paintings, collages, drawings, sculptures and etchings, with 17 works being exhibited in the UK for the first time.

The artist, now 86, was raised in a Portugal dominated by the dictator Antonio Salazar, whose fascist party ruled from 1932 to 1974. The first painting one sets eyes on in the current exhibition, Interrogation (1950), pays striking testament both to the then 15-year-old’s precocious talent and her awareness of atrocities committed by the regime. It’s a disturbing image with a weeping woman sitting on a chair. The interrogators either side of her are intimidating presences, holding a drill and screwdriver respectively. Only visible from the waist down, the one clenching a screwdriver has a noticeably bulging crotch. The sense of menace is palpable.

Rego’s wealthy liberal parents, deeply opposed to the regime, took the decision in 1951 to send their daughter to The Grove School, a finishing school in England after which she won a place at the Slade School of Fine Art. Alongside the sinister Interrogation is a considerably more uplifting painting. Under Milk Wood (1954) was the artist’s winning entry to a summer competition at the Slade. It provided her with an all important confidence boost. Rego was initially unfamiliar with the title they had been assigned and upon learning it was a play by Dylan Thomas set in a small village, she readapted the Welsh coast to her own Portuguese village, Ericeira, depicting sturdy women busily cooking in a kitchen with a backdrop of houses bathed in light.

It was at the Slade that Rego would meet the man she would marry in 1959, the painter Victor Willing. They had a tempestuous relationship – Willing was unfaithful – but when her husband was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1966, Rego cared for him for the rest of his life. In time one finds all of that pent up emotion and anger pouring out into her work. In Girl Lifting Her Skirt to a Dog (1986), the serious-faced girl lifts her dress to a dog who seems not to know where to look. It’s a thinly veiled portrayal of Rego and her dependent, ailing husband. Wife Cuts off Red Monkey’s Tail sees the eponymous wife removing the proud tail with a huge pair of scissors in a clear allusion to castration. She is painting characters from a toy theatre belonging to Willing in reference to one of his affairs.

The 60s and 70s saw Rego and her husband live intermittently in Portugal and the UK before they finally settled in London in 1976. In the initial years after the Slade one finds her experimenting with abstraction yet continuing to condemn the Portugese dictatorship. The canvas Salazar Vomiting the Homeland (1960), with its colourful biomorphic shapes, sends up the detested leader as a blob confronted by a mass of pubic hair representing repressed women (they wouldn’t, for example, be allowed to vote until 1976). The artist made frequent use of collage in the 60s and 70s with the opening few rooms at the Tate revealing how she drew inspiration from advertisements and new stories. Julieta (1964) and Manifesto (For a Lost Cause)(1965) both fizz against planes of popping colour. Each was exhibited at her first solo exhibition, at the Modern Art Gallery of the National Society of Fine Arts in Lisbon in 1965, which won her admirers whilst shocking others.

The subject has long been interested in traditional folk and fairy tales. In 1966, devastated by the death of her father and her husband’s multiple sclerosis diagnosis, the artist went into a severe depression. At the advice of her doctor she started seeing the Jungian therapist, Edward Hirst. Hirst actively urged her to return to her “imaginative source” and consider fairy tales, myths and biblical stories. Rego would gain permission from the Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon to look at and research original folk tales between 1976 and 1978. This contemplation of the likes of Gustave Dore and Walt Disney energised her practice. In those years she was exploring folk tales as representations of human psyche and behaviour such as in the colourful gouache work Brancaflor – The Devil and the Devil’s Wife in Bed (1975). Later in the current exhibition one is presented with the series of disturbing etchings the artist conjured up in 1989, imbuing nursery rhymes like Three Blind Mice with sinister overtones.

Willing’s death in 1988 was followed by his wife’s rise to prominence. Many of the monumental, enigmatic paintings she showed to great acclaim at the Serpentine that year are featured in a single room at the current exhibition. The Dance (1988), one of her most celebrated works, was painted in the year her husband died. Set on a moon-lit beach in her native Portugal, one sees a group of people dancing, including her grandmother and mother. Willing and herself dance arm in arm to the right and yet in the centre, her husband appears again, cheek to cheek with a mystery blonde. He meets the viewer’s gaze unrepentantly. Another painting in the same room here, The Policeman’s Daughter (1987) features one of Rego’s determined girls, her hand thrust deep into her father’s boot in order to polish it. Her virginal white dress contrasts starkly with the black boot. There’s an overriding sense of anger and isolation, the dramatically lit setting immediately recalling de Chirico.

The subject underwent a lengthy period of Jungian therapy to counter demons stirred by Antonio Salazar and her tumultuous marriage to Willing. In the 1990s one finds her switching to pastels, viewing them to be “fiercer, much more aggressive” than brushes. Rego’s acclaimed Dog Women series from the period depicts lone women posturing and behaving like feral dogs. She presents these figures, each acted out by her model Lila Nunes – who closely resembles the artist – as concurrently submissive and independent. An entire room at Tate is devoted to her 2004 Possession series, a no less psychologically penetrating set of works with Rego’s essential surrogate Lila depicted in multiple poses on a therapist’s couch. It’s a reflection on the way women used to be diagnosed with hysteria. Unquestionably they remind one of Lucian Freud.

Throughout her career, Rego has summoned her visual weaponry to denounce what curators refer to here as “injustices”. In 1998 she produced her unflinchingly raw series Untitled, now known as Abortion, again in pastel. The images, featured here in their entirety, depict young women – some still in their school uniform – following illegal terminations. That year, there was a referendum to legalise abortion in Portugal. Thanks to low voter turnout it failed. However, Rego’s powerful series was printed as a rallying cry in newspapers in a second referendum in 2007, which duly passed.

This consistently superb retrospective is concluded on a particularly disturbing note with the artist deploying her emotion-laiden storytelling to protest against the horrors of female genital mutilation. Works like Stitched and Bound and Circumcision (both 2009) are shockingly visceral. Also exhibited here is Human Cargo (2007-8), a macabre triptych evoking human trafficking, the artist inserting some of her puppets into the composition.

Rego’s reputation as a consummate teller of tales on both canvas and paper is further enhanced at Tate Britain. The museum dedicated to her work which she opened in Cascais, Portugal in 2009 is appropriately called Casa das Histórias (House of Stories). Those dark undercurrents of violence, eroticism and oppression seem to be forever bubbling under the surface. In this impressive overview of the artist’s long career, the intimate relationship between Rego’s life and art is revealed.

James White

Featured Image: The Dance, 1988. Photograph by Tate © Paula Rego

Paula Rego is at Tate Britain from 7th July until 24th October 2021. For further information visit the exhibition’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS