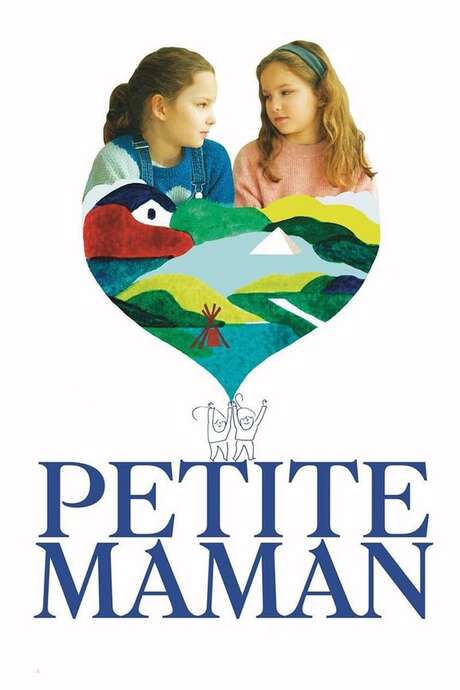

Petite Maman

This gracefully rendered, fabular tale provides an exquisite distillation of Céline Sciamma’s focused and empathetic cinematic style, and it amounts to the writer-director’s strongest work to date. The pared-down, elemental and efficient storytelling contributes to its relative success, exemplified by the swift, unfussy transitions between truth and fantasy; night-time and morning; grief and catharsis. This is one of the most forceful evocations of whimsy recently committed to screen, and its mining of fancy and caprice serves to underscore the acute sense of loneliness and loss, with which the film is primarily concerned.

Nelly (Joséphine Sanz) is an eight-year-old whose grandmother has just died. The girl’s mother, Marion (Nina Meurisse), is stricken and upset. Leaving the care home for the final time, the pair share a tender scene: the child supplies her mum three Wotsits and a juice carton from the backseat, embracing her as they drive away. This sets up the pain of the parent’s subsequent absence, which is also an historical and repeated absence, borne back ceaselessly, so much so that the present becomes the past. A genetic bone disorder runs in the family, a simple metaphor for the emotional debris wrought through lineage.

With Nelly’s father (Stéphane Varupenne), all return to the grandmother’s house and childhood home, serenely placed within fairytale woodland and bathed in an autumnal glow. Marion departs, semi-mysteriously, and in the leafy surrounds Nelly encounters a young girl, also named Marion (Gabrielle Sanz, the identical twin), who mimics her age and circumstances. In fact, Marion’s mother (Margot Abascal) has a physical impairment strikingly similar to that of Nelly’s late grandparent. Sciamma’s screenplay foregrounds the rituals of greetings and goodbyes, and while there appear to be practical ambiguities around the various appearances and disappearances, the essential facts of the drama are not withheld or hidden, but logically pursued, depicted and understood.

Fictions and pretence assume centre stage as the young duo, kitted out in knitwear and dungarees, engage in the business of recreation: acting out detective roleplays and building treehouses. The therapeutics of play and the boredom of confinement are aptly illustrated through DP Claire Mathon’s precise compositions, often embellished with pockets of amber sunlight, spotted against the wallpaper. The French director captures the children’s activities through a patient naturalist lens: the girls make pancakes, mess around, laugh freely. Their dwellings appear to be otherworldly sanctuaries, in which adults, regardless of supposed intimacy, function as spectral presences, channels for mystical occurrences or moments of mere coincidence.

The dynamics of the central friendship seek to blend the memories gathered by age and the textures wrung from childhood. Whether these details are elaborated more through defined images, narrative choices or staged dialogues is probably moot: Sciamma clarifies the cross-generational imaginary in a closing burst of euphoric sentimentality, during which the two girls, fast friends, reach a floating pyramid. They’ve paddled there from across the lake, arriving up close, finding a simple yet sophisticated structure, an encapsulation of the film in miniature.

Joseph Owen

Petite Maman is released in select cinemas on 19th November 2021.

Read more reviews and interviews from our London Film Festival 2021 coverage here.

For further information about the festival visit the official BFI website here.

Watch the trailer for Petite Maman here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS