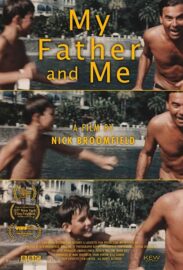

“It was like incredibly intense therapy”: Director Nick Broomfield on making My Father and Me

My Father and Me is the new documentary from esteemed director Nick Broomfield, the man behind Kurt & Courtney, Biggie & Tupac, Whitney: Can I Be Me and two films about Aileen Wuornos. His confrontational and seemingly chaotic documentary-making style has made him one of the most revered artists in the genre and his work has long inspired other documentarians such as Louis Theroux. After five decades of focusing his attention on gritty topics and troubled subjects, the prolific filmmaker has turned the camera on himself, his father, Maurice Broomfield (who was renowned for his photography capturing images of working men in factories) and their relationship. Broomfield’s film is being screened on the BBC in tandem with the launch of a new exhibition of his father’s work at the V&A in London.

The Upcoming had the privilege of having an in-depth chat with the filmmaker about what motivated him to make the film, how it contrasted to work he has done previously and why he thinks his most personal film to date has struck such a chord with audiences.

Hi Nick, it’s such a pleasure to have the chance to speak to you. Maybe you could kick off with a brief introduction to this documentary, which I believe you made a few years ago, but it’s being brought to the fore again in line with a V&A exhibition of your father’s work?

Well, it’s actually not something I made long ago, because one of the interesting things working with the V&A is that they work much slower than working for TV or something like that. And because of Covid-19, and because of their own storage problems and all the rest of it, the exhibition kept getting moved. So, it’s finally opening on Friday, but, kind of long story short, I’ve probably made at least three different versions of the film. Because, for example, it was at the New York Film Festival a couple of years ago. And I went to it and then I thought: “Oh, well, maybe the music isn’t quite right.” And then: “Maybe I haven’t really got the tone of the film right.” And then I completely recut the film and changed the music. So the film, actually, that you have, I think was finished in late 2020. You can change your film so much in the editing room, just totally. And obviously, with a family story, you can tell that story on so many different levels. And I think one of the challenges was to try and find a level that might also mean something to somebody else, who has their own family and their own relationships. So I wanted to tell it at that level, rather than maybe going into gripes you might have all the time. It was a great opportunity to really look at my family in a way that I hadn’t before. Because in the editing room, you really need to kind of crystallise your thinking in some way. And, for example, although the film’s very much about my relationship with my father, and our differences in work and our differences in background and that sort of thing, my mother died when I was quite young and when I was editing the film, I realised I’d never really paused to think very much about her role, what she had given to the family and all that sort of thing. Because the family dynamic obviously changed enormously once she died. So it was also like incredibly intense therapy for three years. I was doing other films as well. Although I’d been very frightened of making the film, I think it was a very valuable time to actually reflect on what has happened and in a way that probably normally you wouldn’t have, you know? But I don’t know if that’s a description of the film. Really, I don’t know what the film is. I suppose the film’s about family relationships. I still feel quite close to it.

Over the decades you’ve made such an array of films and tackled some really challenging topics and subjects like Whitney Houston and serial killer Aileen Wuornos. What was it like to look more inward? And what do you think you learnt from delving into the lives of other subjects which helped you turn the camera on yourself and someone close to you?

Yeah, well, funnily enough, making the Aileen Wuornos film was a very emotional experience. A lot of the other films, you’re more distant, and you’re just trying to tell the best story or the most accurate story that you can come up with and you’re not that emotionally involved. I mean, with the film about Whitney – I really knew very little about her. When I started filming, I wasn’t the most enormous fan of her music. But by the end, I kind of had almost sort of fallen in love with Whitney because I knew her story. And it was so tragic. And I think she’d been such a kind of wonderful person, just such a wild and free child at the beginning and was sort of backed into a corner. So, one ends up identifying with people that you don’t really know very well. I mean, I think with Aileen Wuornos, she was somebody who had had such a tragic childhood and then was so abused by the justice system. There was something very childlike about her and it was impossible not to feel awful about what happened. I remember being really upset when she was executed. Well, we all were really. So the Wuornos film was very, very emotionally draining, in a way that the other ones probably hadn’t been. I guess my films have become more and more inward, maybe, in a way. Or probably gentler films, I would say, more sensitive films, probably more inward-looking. The film I did about Marianne and Leonard too was a much more internal kind of film than I had been making. And so, My Father and Me was on that way of thinking. And I made it immediately after, or during the time I was making Marianne & Leonard so there was quite a lot of self-examination, I guess, from the period when I was growing up and falling in love for the first time and just thinking back to that whole world then, which seems such a different place to now. And that’s, of course, really interesting. Because we kind of live in a way that we think everything is static and going to be there forever. And, of course, when you look with hindsight, everything is constantly changing so fast, including people’s worldview and their culture and their attitudes and their feelings about politics, and all those kinds of things. You can see such enormous change has happened in that time. And obviously, one’s family, to a certain extent is an embodiment of that. One’s parents represent particular attitudes and a set of values that are probably very different from now. And that’s reflective of the time when they grew up and their histories and stuff. So in My Father and Me, I look at the histories of both my mother and my father, which were very, very, very different. And then you try and get a sense as to how that affected you as a kid. It’s obviously endless, you don’t really come up with a resolution. But I’m sure in your own, rather much shorter lifetime, you’ve probably been through lots of different kinds of influences, some of which have stayed with you and some of which you think were good; some were not so good. And you end up being a sort of tapestry of all those things, really. So I guess that’s what the film tries to be, it’s a kind of tapestry of that type. Celebrating the things that you think are wonderful, the things you admire in the other person or in yourself or in the world at that time. So yeah, it’s certainly a different exercise to just making films about other people.

One of the things I love about it is that through going back and delving into your relationship with your father you also traverse so many other topics. By going back into your parent’s histories, you’re also covering differences in political views, the changing face of Britain, and also your contrasting approaches to being creative. In particular, you mention in the film how you clashed in terms of you having a more chaotic approach to your work whereas his photographs are quite staged, presenting a more optimised view of the workers he captured. What do you think some of the themes are that come out of the film?

Well, I think there was a big artistic difference between my father’s work, which was very, very precise, and very staged, very beautifully lit, to the most minute detail, and my work, which was much much more spontaneous and was all to do with the moment and all to do often with chaos and things that were very much unscripted and kind of semi out of control. Because I thought that that was closer to a particular truth. I guess my father was looking for a different truth. He was making something that was much more a tribute to the working person and to the achievements of our creativity and making these amazing machines and industry. And he was kind of fascinated by machinery, which is a fascination I’ve never had. And then, of course, he was a perfectionist in his photography, which I realise more now. He was very exacting. He was pretty casual most of the time, he was up for a lot of fun: he loved the sun, and he was always paddling around basically with no clothes on, and was just sort of very fond of throwing himself into any body of water. He definitely knew how to enjoy life. But with his photography, he was very exacting, very precise. He hated snaps, holiday snaps, he was scathing about that. And you had to sort of “do photography” for a week, you couldn’t just go out and take a couple of pictures. It was a bit like being in the army or something. And I guess I inherited a certain amount of that, regretfully, you know, in my work. Although it looks chaotic, it’s quite precise in its own way. And I’m not sure, necessarily, that’s the greatest way to work. I mean, I guess it’s effective, because you’re so focused, maybe, I don’t know. So as a kid, you do pick up a lot of stuff subliminally, almost, from your parents. But I guess if you want to hone a particular art form, to a great extent, that requires a lot of discipline, requires a lot of focus, it’s not going to just happen. Unless you’re a complete genius, which neither of us were. It’s very much about discipline and learning stuff and doing things in a repetitive way so you have a particular method of doing things. So I think I sort of learned it in my own way, from him. I think it took a while for me to really understand his work, too. And I think a lot of that has to do with his background, which is that he left school when he was very young, went straight into a factory. And then, fortunately, he studied photography and kind of got a break. And then ended up photographing the very environments in which he had grown up. But he had a lot of respect, I think, for the people, which probably somebody who hadn’t worked in a factory wouldn’t have, he had that sort of understanding. And I think his work is very much a celebration of that, really. So I was coming to it from a very different perspective. I have a sort of very middle-class background on the whole because my father was very successful. I grew up in North London, went to all these private schools, which I did very badly in. But it was very, very different from his world, so I didn’t really understand, properly, his photographs. And oddly enough, Martin Barnes – I don’t know if you know him, he’s the main curator at V&A – he had a great relationship with Maurice and did a lot of recordings with him. And his father came from a similar background to Maurice and Martin had much more of an understanding of Maurice’s work than I did. So obviously, I learned a lot. And I remember when Tony Benn, who then was Minister of Labour, opened one of Maurice’s exhibitions, he said it was a sort of celebration of the working man and he wished kids at school would learn about the working man from these photographs and that sort of thing. Which I thought was really interesting, because I hadn’t really seen it that way at the time. And I like so much more gritty kind of photography. But that’s kind of inevitable in a way. And I think my father found my work unnecessarily kind of confrontational and aggressive and not what he thought documentaries should be. My uncle worked with David Attenborough and I think he thought that was much more – not that I’m saying David Attenborough work isn’t brilliant and fantastic – but it wasn’t breaking lots of rules, it wasn’t challenging to our particular society. My mother was very left-wing politically, I think she was probably much more angry about things, having been a refugee and living in England, which I think was fairly intolerant of foreigners. She had a bit of an accent. She was much more outspoken than my father would ever be, he was a very gentle sort of person. So I guess you end up being influenced by both your parents in different ways.

What do you hope that people will take away from watching it? In some senses, it’s a great accompaniment to the exhibition because it’s telling the human story behind those photos. But do you think also people will watch it and recognise elements of their own relationships with their family and there’s something quite educational and important about going back a bit in British history and reflecting on how things are today?

Yeah, I think a lot of people will think about their own families and their own relationships and their own situation. And I think that’s really probably where it takes most people. So obviously it’s about my father and me. But it’s probably more about putting people in touch with their own families and making them think about their own history and their own time and their own relationships. And I guess we all actually spend quite a lot of time thinking about our families. Families are all a bit of a conundrum, you can’t quite work out what caused what, was this right or was that wrong? At a certain point, it’s a decision. We all have the ability to make a decision just to make things work and not just dwell on everything that doesn’t work. Which certainly is what I think probably happened with my father and myself. We just decided to enjoy what we had, which was fantastic. I was very lucky because my father lived to his 90s, so there was plenty of time to have a period of conflict and then a period of resolution. Some people I guess aren’t lucky enough to have that sort of time. I think it moves people because it puts them in touch with their own emotions, emotions that we all have. I think that’s what works best about it. Because when I made it, I felt this was kind of a little film that is completely non-commercial and it was a wonderful privilege to make it and I was incredibly pleased. So I was really very, very surprised when it was shown for the first time on BBC. I’ve never had such a reaction, actually, to a film from a transmission. And I got wonderful emails from people I didn’t really even know, who were so moved by the film. Even Attenborough and people that probably hadn’t necessarily liked much of my other work! So, it was also great just to see that when you deal with your gentle side that it opens a lot of doors, a lot of people identify with that sort of side of thing.

How does it feel for your father’s work to be immortalised or be reaching a wider audience with this exhibition, for your film to be showing at the launch with a Q&A and also for it to be going back on the BBC next week? Particularly given the last 18 months we’ve had with people not able to get into exhibitions or get to the cinema to watch films – what’s that feeling like for you?

Well, I obviously feel it’s great that it’s happening and it’s sort of a great honour really more for my father’s work. But obviously it would be great if he was around to celebrate it too. It’s kind of a celebration, I guess, of something, which is wonderful. He loved having exhibitions because he could invite all his buddies along and get the family along and have a good drink. So I’ve kind of made the opening evening very much like that, reached out to all his friends, some of who run the local photographic competition in schools, which my father started in, all his various chums from around there, and a lot of my friends who knew him growing up. So it will kind of be a fun evening, I think, of people who know each other. He married Susie Thompson Kuhn in the last sort of third of his life. Susie had lots of Finnish relatives so they’re all going to come. It’s great to have that excuse to get the whole family together in a kind of situation that I think my father would have loved. So I’m looking forward to that. It feels very sort of calm in a way. It just feels like a kind of resolution of lots of loose ends. So actually it just feels very sort of calming, which is unusual. I mean, normally when you finish your film, you’re always worrying about what isn’t working. And there’s generally plenty of things that aren’t working. But I didn’t kind of have that nagging feeling. It’s kind of just what it is. And that’s, that’s a nice feeling.

Do you already know what you might work on next? Do you think you’ve ticked the box of doing this very personal type of film and you’ll go back to looking at other subjects, or do you feel like there’s more to explore?

I’m doing something kind of about the 60s, which we’re filming at the moment. And it’s obviously a period that I know and a lot of my friends know. I’ll probably do it about a particular relationship in the 60s to try and keep it as personal as possible. So I don’t think so. I mean, I made Last Man Standing too, which came out in the summer, a film about Biggie and Tupac again, about a very violent subject, a very, very different kind of subject to you My Father and Me and the later kind of films that I’ve made. And I did find it quite awkward going back to it actually, it did feel I was like going back to a much earlier part of my life. It wasn’t an enormously enjoyable film to make, partly because I think the situation in the States has got worse rather than better. I think for people living in Compton, there’s a lot more anger now than there was in 2002, when I made the original film. So I think America’s in a very sad state at the moment, it’s kind of so polarised and I think that film was very much to do with that whole polarisation stuff. So yeah, I do feel more comfortable making a different kind of film now, which is great. You don’t want to carry on making the same goddamn film for your entire life, you know, you want to learn stuff. I guess what I’m saying is, I learned an awful lot doing My Father and Me, I learned a lot doing Marianne & Leonard and I actually learned a lot on the Whitney film. Well, that’s the fun thing about making films is you’re constantly discovering things you didn’t know or emotions you didn’t know you had. So that’s great.

And finally, do you feel optimistic about the arts industry post-pandemic? How does it all look from where you’re sat?

I really hope cinema has a sort of rebirth. Because it’s so exciting seeing a film with a group of other people. I think people do communicate, somehow there’s some sort of weird communication – you know whether the film’s going down well or badly and no one’s saying anything, you can just tell. There’s some kind of spirit in the room that’s telling you. So that’s the magical thing and I think we need to keep that. And I just hope people get over their fears and get used to meeting in that way. I mean, I think COVID has made people so separate. And they need to sort of get back into more of a sort of social situation. It’s actually great in England that people aren’t wearing masks. Whereas in America, where I normally live, everyone’s still masked up. But I think people are getting back into things I mean, people always say, “what’s the future of documentary?”. And obviously, there’s a lot of funding of it. It’s a much more commercial form than it was years ago. But I think it’s also becoming much more kind of, formulaic than it was. The wonderful thing about people like the BBC, which is very unusual, is that it’s much more experimental, in a way, and much more drawn to the arts, than mainstream streamers, who are all to do with ratings and, you know, everything is about ratings. And I think that doesn’t bring out the most interesting work, it brings out work that is kind of predictable because you’re always looking at what was successful before. And so you commission on the basis of what you think will kind of carry on a particularly successful run in some way and often it’s the left-field films that are the most special. And I think it’s harder to get those funded now. And documentary makers are forced into making rather obviously commercial films. I mean I was always attracted to documentary because it was kind of like the last wild frontier. You could sort of go off with your horse and make some crazy film. And maybe it would be brilliant and groundbreaking. Whereas now I think, people commissioning film want to know that three-act structure before you start. Documentary is all about discovery and coming up with something very different from what you imagine when you first went in. But most commissioning editors and streamers don’t really want to hear that. There’s a particular mentality of playing things very safe, which I think is not what documentary is about. And I was incredibly grateful to BBC for putting the money out for My Father and Me, because it easily could have been a dog, and I didn’t really know what I was going to do to start with. And in the process of making the film we discovered all this archive and stuff. It was a complete fluke that we found that interview with my grandfather and then we found the film with my father. And obviously, you don’t have time to do that kind of research before you submit a treatment, you don’t really know what you’re going to find. So a lot of making a documentary is a leap of faith. And I think a lot of streamers and stuff are not prepared to make a leap of faith they want to know everything before. And I think that’s alien to the form. Anyway, I’m probably wrong.

Fingers crossed, we’ll still see exciting documentaries from you in the very least! It’s been such a pleasure to speak to you, thanks so much. Enjoy the launch tonight!

Thank you very much.

Sarah Bradbury

My Father and Me will air on BBC Four on 10th November and stream on BBC iPlayer. The V&A Museum will celebrate the work of Maurice Broomfield in a display of his photographs Maurice Broomfield: Industrial Sublime from 6th November for a year. The V&A will publish an accompanying book with the same title, written by V&A Senior Curator Martin Barnes and with a foreword by Nick Broomfield.

Watch the a clip of My Father and Me here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS