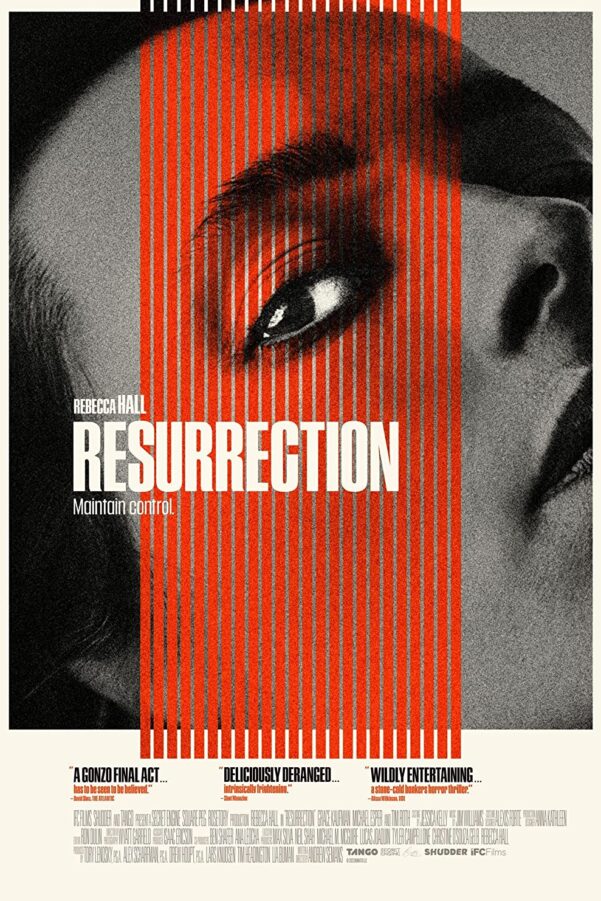

“There’s a huge release that comes with watching someone process that much anxiety”: Rebecca Hall on psychological horror Resurrection

As unhinged, horror-tinged psychological thrillers for this year go, Andrew Semans’s Resurrection and Alex Garland’s Men are probably neck-and-neck for the most out-there final acts. Thankfully, the star of the former, Rebecca Hall, has form on visiting the dark recesses of human experience, having taken on other not-for-the-faint-hearted roles in Christine and The Night House. Still, her turn as Margaret, a seemingly affluent and impeccably in-control single mother of a teenage daughter (Grace Kaufman), living in New York, is nothing short of astounding.

Despite her tough, lean appearance, competence in her high-flying biotech job and perfect want-for-nothing life, something unsettling seems to be simmering underneath Margaret’s varnished veneer. And when a figure from her past (a startlingly chilling Tim Roth) starts to appear in unexpected places, that something unsettling spills over into a visceral manifestation of anxiety, and an unravelling of untold proportions. On one level, it’s an unnervingly realistic depiction of the crippling dread one can feel when becoming a parent, and the perversely intoxicating power of psychological manipulation and control; on another, its heightened nature takes the audience on a far more metaphorical, existential journey.

Never one to rest on her laurels, Hall has always taken on eclectic roles across indie and big-budget films, TV and theatre, from Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige (2006) to Woody Allen’s Vicky Cristina Barcelona, Iron Man 3 to Professor Marston and the Wonder Women. Here, once again, she makes another audacious choice, and one she has jumped into the void of with no holds barred.

The Upcoming had the privilege of an in-depth chat with the actress ahead of Resurrection being released digitally on demand, who spoke about her initial reaction to Semans’s script, how the project seemed the perfect one to take on after the decade-long journey to writing and directing her first film, Passing (a triumphant adaption of the 1929 Harlem-set novel), and the toughest aspects of the short shoot, including delivering a seven-minute dialogue. We also discussed her broader career, how the movie industry has changed since she first broke into it and her rebellion against being boxed into a corner as a “leading lady” by making bold career decisions.

Resurrection doesn’t fit neatly into a genre. What would you say audiences can expect when they watch it?

It’s probably, at its core, a psychological thriller that plays with a lot of different themes. But I think audiences can expect to have quite a thrill ride. Yes, there’s a sense that it deals with very serious things, and it’s pretty heavy, and it’s pretty intense, but I think there is a sort of entertainment factor in the intensity of it that I certainly found quite cathartic to play. And I think it is quite cathartic to watch in a weird way: there is a huge release that comes with watching someone process that much anxiety.

This is one of those films where one feels the need to sit still for a few minutes afterwards to let it sink in, because of the intensity and not knowing where it’s going at each moment. Did you have that feeling when you first read the script?

Oh, yeah – very, very much. The majority of scripts that I read, you sort of know what’s coming, and you’ve sort of guessed it, and it is such a joy and a relief when you come across a script where you really have no idea. And then when it does go there, it’s so galling, that it becomes a must. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that I, in large part, did this movie because I thought that it would never work, which I know sounds completely counterintuitive and insane. But I had this curiosity about it: the sheer hubris of writing this down and saying that you were going to make a movie like this – I found to be so sort of brazen, I was like, “Well, I want to know if it works. So I guess I’ve got to do it!”.

You’re no stranger to intense roles, but your performance here is strikingly committed – firstly, on a physical level, how obsessive about her fitness and appearance the character is, but then of course, beyond that, her unravelling on a psychological level as well. How did you prepare to play Margaret, mentally and physically? Did you have to do any research about what it’s like to be in a controlling relationship, or were you able to draw on anything from your own experiences? How do you make sure you don’t lose yourself and are able to bring yourself back out of it at the end of a shoot?

The eternal questions! I don’t know about the last part of that question. I really don’t. I have a pretty brutal actor shutdown function – like, “End of the day, I now power down, and I will not take this home with me” – that I’ve worked very hard to cultivate. As for the first part of that question… the sorts of things that she is going through psychologically, I think, are… it’s terrain that I instinctively understand. I don’t really understand why, but I sort of instinctively understand, and I did think about too. It wasn’t for nothing that around that time I was watching all those NXIVM documentaries, I suppose. It occurred to me that she was in a cult of one, and she was being severely gaslit, and I think that that is something – on a way, way smaller level – that all of us have experienced, that it’s definitely much more in the culture and things that we’re talking about and thinking about nowadays. So it didn’t feel alien to me to understand her psychological place in the world. I think I understood also the idea of creating a sort of alter ego that is all-powerful, this, “I am a lioness, and I’m indestructible, and I will protect my children above all things.” And, of course, that is constructed in relation to feeling powerless. So it’s always that balance of the two. Really the hinge of the movie is this idea that she does look so strong, she is so powerful, and the guy that is forcing her to unravel is essentially a very sort of weak, schlumpy middle-aged guy with a potbelly, drinking vodka out of a paper bag. He’s utterly unthreatening on some level – she could knock him out immediately – so the tension is in the fact that she can’t because she’s still so affected by him; she has given him so much power. And so, yes, it was very important to me to get physically strong, and convince myself that I was capable of anything in an almost ego-maniacal way. And then it’s just a matter of letting things fire at her so that that all falls apart.

It goes without saying you have to go to some really dark places throughout the film. Was there a scene that you found most difficult to shoot? There’s a seven-minute monologue – was it hard get through that?

Before we started shooting, it felt like it was going to be the hardest bit. I did a lot of work; I was sort of drilling the lines for a long time, and I was thinking about it for a long time. But when we actually got to shoot the monologue, it was by far the easiest scene to shoot because there was only one setup. Andrew just stuck the camera on me; he agreed on the frame, locked it off, pressed record, and then it was just on me to do it. And, actually, we got out of that scene – I think they’d allotted four hours, and I remember the first assistant director being very worried about me and saying, “Whatever you need…I know it’s a really hard day”, and me going, “Yes, yes, yes” – and then we did one take, Andrew was really happy with the first take, then we did another take for safety, and he was really happy with the second take. And then we moved on. The whole thing was done in 20 minutes. So it wasn’t so bad, actually, in the end. The anticipation of it was a lot. I think probably the physical stuff ended up being very gruelling – the fights and just sort of being in that space for a long time. The overnight shoots were just exhausting.

The film works on a number of different levels: you could take some parts of it at face value – the idea of being in an abusive relationship – but then there is this infusion of a kind of mythology or something heightened, where it becomes a metaphor for the anxiety we feel, particularly women, when we become parents – of wanting to protect our children but being unable to. It seems that through a genre like this, you’re able to make that anxiety manifest in some ways. How do you see the multi-layered nature of the film? What is real for you, so to speak?

I think you just said it perfectly, I don’t think I could say it better than that! That’s exactly it. I think it is heightened. It does heighten to a sort of level of mythology. I mean, it’s literally referencing some Greek myths, if you want to get into that. But I do think that it is a sort of mythology for the existential terror of being a mother and not being able to keep our children safe, and the anxiety, and the lack of control. And even on a not-so-epic existential level, on a sort of more domestic level, there’s the horror of when they leave the nest. Margaret is dealing with her teenage daughter who’s about to leave home – that’s not for nothing in the story.

And what about working opposite the amazing Tim Roth? You have some very intense scenes together – did you have a chance to rehearse to be in a safe space before shooting those? Equally, working alongside Grace Kaufman, you make it seem like you have a really lived-in mother-daughter relationship.

Well, with Grace, we had a lot of time to work that out because she shot many more days than Tim did. Tim came in for the last seven days, I think, and we shot all of his stuff then. This was a very small indie: the whole thing was only 19 or 20 days. But Grace, she was around from pre-production, so we could hang out and meet each other at fittings or whatever, and really develop that kind of friendship that stood us in good stead to be mother and daughter. And she is an incredibly intuitive and open actor; she’s very present. I loved working with her, she made it very easy, but it was odd in a way because we were sort of imagining the threat of this other character for that whole time of filming. And then he arrived for the last seven days, and all I did was act with him – everyone else had gone, Grace had gone. So this discrepancy between my imagination of what Tim Roth would do and what Tim Roth did do was also interesting, because I’d spent all this time imagining him, which was not wrong – Margaret’s recollection of this person in her life would be in large parts a sort of amalgamation of memory and not necessarily trustworthy things. So when he did arrive, it was sort of perfect. We didn’t have any time at all to establish anything; we just started shooting, because there was no time. We didn’t talk about it, we didn’t do any of that, we just played the scene, which I found to be probably the best way to do it – because I had no expectation of what he was going to do. And it was incredibly destabilising and sort of scary to then suddenly be across from it, witnessing the thing that I’d imagined for a while.

Coming to your own career, this film came off the back of a long-running project to make your own film, Passing. What was it like to jump straight back in front of the camera? Are you already thinking about what project you might do next? Will you be back in the director’s chair?

Yeah, I do think that I came out of Passing having some clarity about what I wanted out of my acting career – it was never on the table that I was going to give it up. So I did want to go back to acting, but also felt so alive and lit up by directing, and so challenged, that I think on some unconscious level I was looking for something that would merit doing acting instead of directing. And it had to be an enormously steep climb. So this did fit that bill, but it also gave me clarity about wanting to take jobs that are also just fun, and don’t have the pressure that directing does, which is I guess why I’ve just finished acting in another film of Godzilla vs Kong, for example! So I think my career is always going to be a balance of that, and a balance of the unexpected and things that surprise and delight me, and I don’t know always what those things are going to be. But I do think that the next thing I’m going to do is direct again, yes.

Do you think the industry has changed since you entered into it? Would you say there’s more opportunity now for exploring the female experience front and centre in film? Particularly with the thriller/horror genre, it feels like we’re getting into new and exciting territory where we can really delve specifically into the female experience.

Well, I think, when I first started, I was really aware that it was really difficult to have any sort of aspiration as a young woman to be anything that suggested a character actor. Thankfully, and happily, I was put into the leading category pretty quickly. But what came with that was the sense of, “Well don’t do anything dangerous, don’t do anything that’s a little unlikeable.” And that was always the thing that I was attracted to, and I would buck against that – anything that put me in a box forever from jump. I would always make the decisions that I was told I shouldn’t make. And, for a long time, when I started out, that was considered career suicide. And now I think the conversation has broadened. The things that people were saying at the beginning of my career that felt like fringe things to be saying, such as, “There aren’t enough stories about X, Y and Z”, “There’s no diversity”, “Why don’t women do blahdy, blahdy, blah?”, “Why do we always have to look pretty?” – those felt like fringe conversations, but now it feels like we’ve cracked that open. Now, there’s a whole new paradigm. And there is a lot more possibility, but this is also a moment when the film industry is contracting in the face of “how are you going to make money?” and all this sort of business side of things. There’s this expansion in the streaming world, and there’s opportunity and many more platforms for many more voices, thank goodness. But there’s also the simultaneous contraction about what can be mainstream. And I think there’s a real tension there – I don’t know what the outcome’s going to be, but we’re definitely on the precipice of change, and it can only keep happening.

Thanks so much for sharing all that with us. We look forward to everyone else having the chance to see Resurrection!

Thank you!

Sarah Bradbury

Resurrection is available digitally on demand on 5th December 2022. Read our review here.

Watch a trailer for Resurrection here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS