Spain and the Hispanic World at the Royal Academy

This exhibition owes its existence to a book a wealthy American boy picked up about Spanish gypsies (“the Zincali”) in a Liverpool bookshop on landing in Europe. Before visiting Spain, Archer M Huntington’s lifelong fascination was piqued by that book and he founded the Hispanic Society of America, a museum and library in New York, in 1904.

Spain and the Hispanic World at the Royal Academy uses artefacts from the collection to take us through 5,000 years of history, from early Celtiberian settlers and the Romans, through the Muslim leaders’ rule in Al-Andalus, the regaining of power of Catholic rulers and the colonisation of the Americas, and into the modern era.

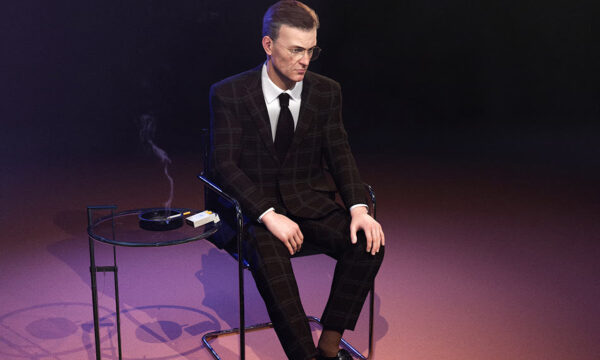

The old masters, El Greco, Diego Velazquez and Francisco de Goya, are represented. A portrait by Anthonis Mor of the 3rd Duke of Alba is mesmerising: staring defiantly down time, his beard and sideburns still wispy, the baton of command is wielded and his armour layers across his body in perfect design, reaching a heart shape at the elbow. Goya’s 1797 portrait of the Duchess of Alba sees her pointing to “Solo Goya” (Only Goya) written in the sand under her feet as she stands before her estate in mourning black lace. We are told the painting had great personal significance to Goya, who kept it in his studio long after the subject’s death, hinting at some redacted romance.

One of the greatest treasures here is Giovanni Vespucci’s (whose uncle Amerigo gave the new continent its name) 1526 world map, with an incomplete curved shoreline being the extent of the knowledge of America. It’s a fascinating artefact, showing a worldview that is rapidly expanding.

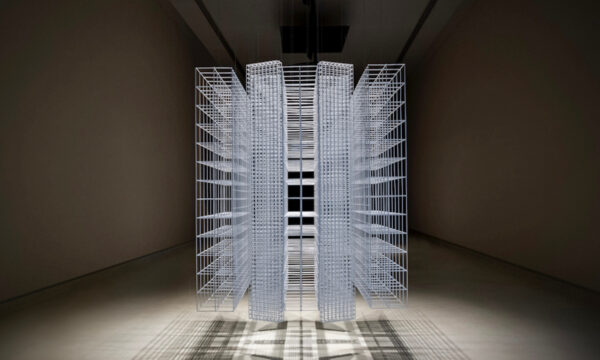

Religious art is prominent. A monstrance is mounted on a lapis lazuli plinth that looks like a cross-section of the cosmos, while it duplicates itself in ever smaller tiers, like its reaching out to God. Some remarkable works come from the mix of Spanish myths and preoccupations with the crafts and materials of the indigenous people of South America. The saints are given an even more bombastic depiction in their defeating of the forces of evil. A proud little sliver lion hot water bottle has been rendered a cheeky Dr Seuss character, rather than the king of the beasts, by a Peruvian artist who would never have seen a lion, and on the basis of the adorably unrecognisable work, was misled by any pictures.

There are beguiling curios too: a book of hours, commissioned by a grieving wife, has striking black pages with writing in gold and silver ink. A paper view of the plaza of Mexico City in 1796 has every ornate balustrade, loping cursive letter and cobblestone rendered with delicately razored precision: it’s a testament to mind-boggling patience and fastidiousness. Strangely, one of the most evocative cases is a collection of 15th and 16th-century door knockers, which is not something generally seen on display and yet they conjure some aspect of living then. There are outlandish designs, with dragon heads and crab claws in beaten metal, both intimidating but also whimsical.

There is a lot to see here. There is a wildness to the sheer scope of the timescale and the range of objects, as can be the way with personal collections – but that only adds to the interest. The richness of the first half means that the move into the modern era feels a little anticlimactic, the last room not being a memorable end. But the sheer complexity and drama of the history makes this worthwhile: an idiosyncratic deep dive into one of the most glamorous and mysterious of European countries.

Jessica Wall

Spain and the Hispanic World is at the Royal Academy from 21st January until 10th April 2023. For further information visit the exhibition’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS