“Australia Day is called Invasion Day by indigenous people – if they want everyone involved, then change it”: Ivan Sen on Limbo at Berlin Film Festival 2023

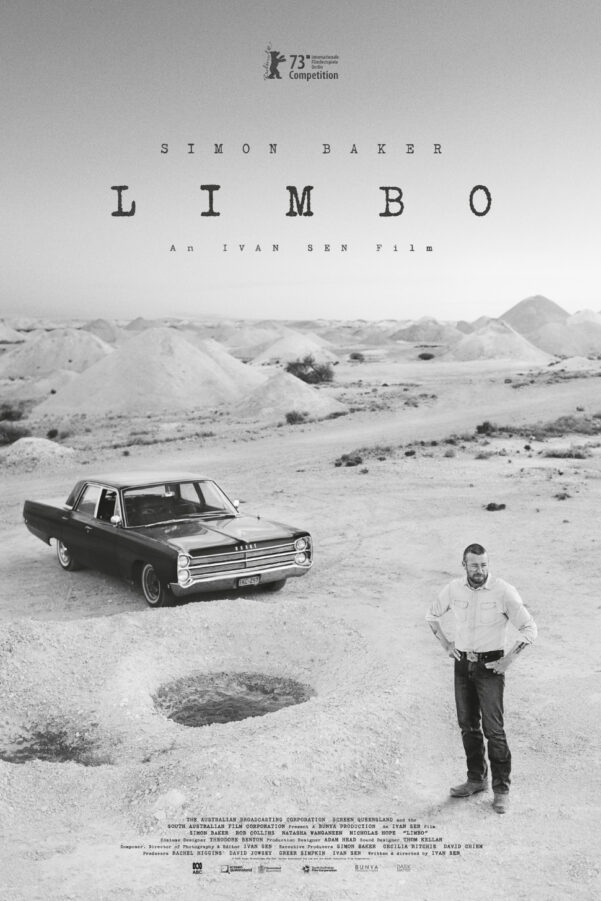

Racial tensions simmer to great effect in director Ivan Sen’s Limbo, premiering in Competition at the 2023 Berlinale. Filmed in austere black and white, the film follows Travis Hurley (Simon Baker), a police detective (and drug addict) dispatched to the wilds of the Australian outback to investigate the unsolved murder of an Aboriginal woman from 20 years earlier. We sat down with the director at this year’s Berlin International Film Festival, and discovered that Limbo might be the last film credited to Ivan Sen, even though the director isn’t planning to retire.

Were your financiers okay with Limbo being shot in black and white, or was there concern that it could harm the film’s box office prospects?

We’ve signed a contract to deliver a colour film; almost every contract says that you’ll deliver a film within a certain amount of time, in colour. But I don’t take much notice of contracts, and I kind of do what I want (laughs). But the ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation, who funded the film) – we didn’t tell the ABC until they saw it. I mean, the day before, we said, “By the way, it’s in black and white”. And then they watched it, and said, “great”. The ABC haven’t played a black and white show for… they can’t remember the last time. It’s been, I don’t know – 20 years? Initially, I was trying to shoot the film on 35 mm film, because I don’t like digital colour. I don’t think digital cameras are very good at showing the human face – it‘s difficult to feel the face with digital. So that became almost impossible because film is now extinct in Australia – you can’t process, you can’t transfer, so we have to send the film to LA, and then it comes back. There are all kinds of problems, so I decided, “Okay, if I shoot digital, I’m going to shoot black and white”. I wanted some nostalgic feeling that film could give in colour, but I think in black and white, digital is a lot better. Because it doesn’t have to show colour, but it’s very good at detail and contrast. For me, the characters in the movie, they’re all living in a memory, and I wanted the black and white to feel like it was now, but also a memory at the same time. The location also has a very good tonal range for black and white. The ground is white, because of the minerals in the ground, so the white ground and the sky, the dark sky, and the black car was always going to give me enough contrast for that black-and-white image to work; because, I mean, some people shoot black and white films, and everything’s grey. So it was very important to have all the elements working together for the contrast. So that’s why it’s in black and white.

Did Simon Baker need much convincing to sign up for the film?

He loved it – he just loved the script. Simon came on board straight away. I met Simon many years ago, like 20 years ago, in Sydney. We’d talked about another project, which didn’t happen. I always really admired Simon’s subtlety as an actor, and I wanted to have a chance to show his subtle abilities in a cinematic way, not a TV way.

You direct the film, operate the camera, edit the film…

I do more than that, but I don’t talk about it (laughs).

But is it necessary to perform all these roles to get everything exactly how you like it?

It’s like painting: grab the brush and the colours, and paint and paint and paint, and then come back and paint over, over, and over, more and more. To me, that’s how I enjoy filmmaking. In the morning, when I wake up, I get excited for the creativity. It’s passion. Because if I’m making a film and my actor is in the next room with a cameraman, and I’m here looking at it on a TV screen, that’s not being creative. That’s making factory work; that’s not art.

Working in such an isolated location, is it difficult to find local casts for smaller and bit roles?

I’m very experienced in trying to find local casts, especially kids. I’ve been doing that for a long time. The kids came from the town (Coober Pedy) and what’s very important is that all the children are very comfortable with each other. So when I cast locals, I cast groups, so they’re all a family unit. When they come, they come as a family: cousins, sisters, brothers, and so they feel much more safe, and you also have less people to deal with. You have one mother and three kids or something like that. But the funny thing is that I didn’t find them until a week before we filmed. It was very nerve-wracking. That’s the problem. It’s very difficult to find the right kids, but when I found them, they were fantastic. They learnt their lines like that (snaps fingers) – very, very fast. I’d like to keep working with those kids in the future.

Have you encountered much racism as an indigenous man in the film industry?

The industry is pretty embracing. The film industry in Australia is very left-wing and embracing of indigenous perspectives. There’s been a lot of support from the government too; more the left-wing Labor government than the right-wing government. But when I was young, I had a lot of racism in school from white kids. I was never that dark, but they all knew I was Aboriginal. But at the same time, I also got on well with white kids; very well, but within my family, because I have a European father, my Aboriginal family would also be racist towards me, my European side. So I copped it, got it from both sides, attacked by Aboriginals, and attacked by white people. And you’re in the middle.

Where is your dad from?

There’s a big story about that. My grandfather’s from Germany, and he was a soldier in the war, and after the war he lived in Yugoslavia. My father was born in Croatia. He escaped and ended up on a ship to Australia, and he eventually met my mother, working in a tobacco field. Italians used to grow it in Australia, and my father was always with Italians. There’s not many Croatians around, so he moved with the Italian community, and he married my mother, saw her working in the field. We were surrounded by Italians when I was young; Italian was my number one language. My real name, I just found out last year, is Schunn. Not Sen. My grandfather changed it after the war because he didn’t want people to know he was German. So now I want to change it back. I was going to put my name in the credits to Schunn, but I ran out of time. We just finished the film last week (laughs).

There was no time to change your name in the credits?

I sent the film to Berlin, and thought, “I forgot to change my name!” I make it on my computer, and then I upload it straight to Germany.

There’s always the next film.

The next film will have Ivan Schunn.

Why is that important?

Because for me, Sen doesn’t have a lineage. It’s not from history, it’s not from the past. That’s important, and my children will change their name to Schunn. I think it’s important to see where we come from. Sen, I mean, people have that name, and when I grew up, I didn’t know where this Sen came from, because my father was never with us. So recently we connected with our family in Europe; in Slovenia, in Croatia.

The Berlinale synopsis describes Limbo as “desert noir.” Do you agree with that assessment, and was that the sort of genre you were going for?

I think every film has several genre definitions. It depends how you personally feel about what it is, but for me – it’s a crime drama, and it’s also a neo-Western, and it’s also an outback noir. It’s all these things, but the important thing for me is that the core is the drama, that’s what holds it together. I mean, Star Wars can be thought of as different things as well. Star Wars is a Western, right?

What sort of reaction to the film are you anticipating in Australia?

Australians are always interested to see the outback as a stage, because believe it or not, most Australians have never been to the outback, and so it’s like a fantasy for them. They know it’s there, but they never go there. So they enjoy seeing their own country without having to get up and move to see it. They like to see their own country.

As an indigenous artist, do you have an opinion about the increasing backlash against Australia Day (celebrated on 26th January, when the first British fleet arrived in the country), and the movement to change the date?

It depends on what Australia Day wants to be, and what Australians want it to be. If they want it to be an exclusive celebration for whites, then keep it as it is. But if you want to be inclusive, then it’s got to be changed to include the indigenous people. The question is for Australians – do you want it just for yourselves or do you want to share it? For indigenous people, it’s our day of mourning; this is when we lost the country to foreign invaders. So it’s never going to be a celebration day, never, no matter what they want to call it. Australia Day is called Invasion Day by indigenous people. If they want everyone involved, then change it. If they don’t, keep it. Because we’re still going to have our day of mourning regardless.

Oliver Johnston

Photo: Jens Koch

Limbo does not have a UK release date yet. Read our review here.

Read more reviews from our Berlin Film Festival 2023 coverage here.

For further information about the event visit the Berlin Film Festival website here.

Watch the trailer for Limbo here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS