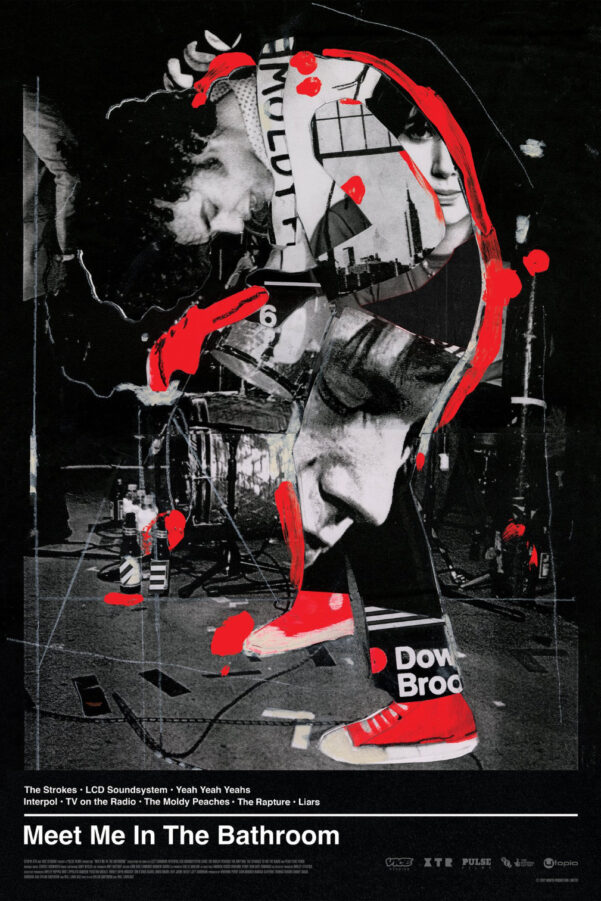

“We tried to situate the viewer in that time and let it unfold in an immediate, immersive way”: Dylan Southern and Will Lovelace on Meet Me in the Bathroom

Meet Me in the Bathroom isn’t your average music documentary. Based on Lizzy Goodman’s book of the same name, it transports viewers back to the New York indie rock music scene of the early 2000s, where the likes of The Strokes, The Moldy Peaches and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs were exploding. Through raw archival footage overlaid with audio interviews from the time, directors Will Lovelace and Dylan Southern place their audience in the era, rather than looking back at it through today’s lens. Viewers see both the sleaze and the innocence of the burgeoning music scene, a time capsule of a period on the cusp of the monumental change the millennium would bring across technology and culture, as well as how cities themselves shifted and changed through forces such as gentrification.

The Upcoming had the pleasure of chatting to the filmmaking duo, who first cut their teeth making music videos for acts from Bjork to Arctic Monkey to Idles, then captured the pinnacle of Britpop on-screen in the form of 2010 Blur doc, No Distance Left to Run, and LCD Soundsystem 2012 concert film Shut up and Play the Hits. We discussed why they wanted to adapt the book, the difficulties and joys they had in sourcing the footage, and the questions they think it raises about the way music is created and consumed today.

Thanks for taking the time to speak with us. Could you start off with a brief introduction to Meet Me in the Bathroom? What can viewers expect when they watch it?

Dylan Southern: So this is a feature documentary that was inspired by Lizzy Goodman’s 2017 book about the music scene in New York at the turn of the millennium. And the film that we’ve made, it’s kind of a time capsule that hopefully transports people back to that time (if they lived through it), or introduces it to them if they didn’t. It basically charts the early years of bands like The Strokes, Interpol, the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, LCD Soundsystem, amongst others.

To state the obvious, you guys are British and weren’t in New York at that time. When you picked up the book, what made you want to recreate it for the screen, rather than focus on a scene in the UK? What was it that inspired you?

DS: Well, our first music documentary was about Blur, so we’ve already done a kind of seminal English band. Our second documentary was the LCD Soundsystem concert film, Shut up and Play the Hits. And there was a weird piece of serendipity in that Lizzy, who wrote the book Meet Me in the Bathroom, first came up with the idea when she was in the crowd at Madison Square Garden for the LCD show, and that’s where the seed of the idea for her book came from. And we happened to be there filming that show at the time; we didn’t know each other, but then, fast forward a few years, and a friend of mine who works at the publishers gave me a galley of the books, and I started reading it. And then, suddenly, four hours have passed and I’ve been voraciously flipping through it and just really enjoyed the sort of rawness and honesty of it. And we were fans of that music at the time, 20 years ago, as well. And I feel like England played a big part in the New York scene in a weird way – it was kind of the British music press getting behind it that made it, to an extent, what it was. So it always felt like it was happening here, as well as it was happening in New York.

Of course, film is a completely different medium to books. When you’ve got all of those pages in front of you, where do you begin in terms of transforming it to something visual? Meet Me in the Bathroom doesn’t take the form of the conventional music documentary – there’s a specific rhythm to it, something more poetic and fluid in the way it’s put together.

Will Lovelace: I think when we first read the book we both thought that the first part of it was the most interesting – the early years when The Strokes and The Yeah Yeah Yeahs and Interpol and all those bands were starting to emerge. It felt like that was the most interesting part of it, both what was happening musically, but also what was happening in the city – that felt the most fascinating part. So we made a decision quite early on that we wanted to make a film that was a companion piece to the book, but concentrate on those first few years. And we wrote a version of how we thought that story would play out, thinking of each of those characters as coming-of-age stories. In terms of the archive, we didn’t really know what existed. We knew the obvious stuff, but we hoped that there would be some great stuff out there. And, like Dylan said before, we were a similar age to some of these bands and we were filming less successful bands ourselves back in the UK, so we thought there’d be people like us who had filmed the bands and taken photographs. It was a question of trying to search that out, really.

DS: But the starting point was to look at what the book achieved so successfully, but then think about, “Well, that does things that a book can do because it’s that form”. So our approach is, “What can we do in a film that a book can’t?”, and the thing that we could do is really bring that time to life. And that then informed the decision that this would be 100% archive, because we didn’t want that VH1 Behind the Music [vibe]. No one wants to see people our age talking about how great the past was. So we tried to situate the viewer in that time and let it unfold in an immediate, immersive way.

What about going through all that archive material? It must have been tricky condensing down so many hours of footage, and yet equally really exciting – like digging through a treasure trove. What were some of the highlights and challenges of that process?

DS: It was interesting because it was never… we didn’t amass all of the archive and then start the edit, we started the edit with probably 20% of the archive that we would need. And then it was really a detective process of… we’d written the narrative, and, as Will was as saying, one thing we wanted to do was to make it universal, rather than just too music nerdy. We wanted to find something to latch onto with each character, which was the idea that these are all coming-of-age stories set in a very specific place and time. So Karen is this shy, young girl coming to New York and discovering this scene, and then creating this on-stage persona, and then also [facing] the dangers that brings with it. And James Murphy coming of age a little bit later than everyone else, and almost by accident. We were looking for these contrasts, and, in the archive, we were looking for ways to tell those stories. But, also, when something came in that was a surprise and we didn’t know we were going to get that, we had to be adaptable as well, to change from the plan that we had. It had to be a really organic, adaptable process, based on what was out there. We’d never made a documentary in that way before; the previous one was a concept film, and the one before was perhaps a more traditional music documentary. But, no, it was an amazing challenge. You’d have periods where you didn’t think you were going to find something for a specific bit of the story and then at the 11th hour, something amazing would arrive. It was lots of peaks and troughs. And, in between, there’s us and the team that we were working with, developing insane detective skills to track stuff down. Will would notice a MiniDisc player in a music photographer’s photograph, and then we’d try and discover who the journalist was who owned the MiniDisc recorder and if he still had the MiniDisc recording and, you know, in some cases they did and we were able to, where possible, use that to let the bands tell their stories back in that time, rather than rely totally on contemporary interviews.

WL: There were definitely a few dead ends as well. We spent a year chasing a bit of footage and eventually got a VHS tape, which said “The Strokes” on it, and was apparently the recording of their first-ever NME shoot. Then when we got it digitised and played it, it was Christmas Day TV, and they’d recorded over it with the Queen’s speech or whatever. So, there were a few missteps as well.

It’s easy to imagine that being case more often than not, because technology back then – once it was lost, it was lost. Did you have a favourite piece of archival material that you discovered, and when you watch the film back now you’re like, “Oh my gosh, that is just the best bit for me”?

DS: There are lots of little bits like that, and sometimes it’s hard to separate the footage from the process of finding it. We didn’t have LCD’s first show in London for a long, long time, and we didn’t think we were going to be able to get it, and, obviously, that’s such a fundamental part of James’s story because he’s just in ascendance as the other bands are falling apart a little bit. So we really, really needed that. And then, at the 11th hour, we ended up getting tapes from two different cameras. Nobody knew two cameras were filming at this thing so that was quite amazing. But I love the early Strokes stuff: there was a lady called Nancy who was a photographer and she hung around with a lot of the bands and had a video camera. We managed to get out to LA, where she had a lockup and she had a suitcase in this lockup untouched for a decade or something, which was full of undeveloped rolls of 35mm stills, photographs and loads of DV tapes. There’s that stuff of The Stokes before they’re even signed, messing around on the subway, and that just really showed them as a solid unit, as these young guys about to explode.

WL: I really like the scene that starts the film, which is Adam and Kim from The Moldy Peaches in their apartment, recording their album and just… that stuff feels so innocent, it was amazing to get that footage. It just seems really fun, and you get a real sense of who they are.

DS: What I love about that as well is there’s a real innocence to it that nowadays – everyone’s filmed on phone cameras all the time, and everyone knows how to present themselves. But the great thing about all this footage… yeah a few people had DV camcorders and stuff, but nobody’s expecting to be filmed. So there’s less of a mask kind of thing.

It’s so true – whenever old photos resurface from the 90s of celebrities or parties, one suddenly realises how everything nowadays has a kind of sheen; everyone is so self-aware because they know how many people are going to be taking pictures, videoing, and that that footage will be all over social media. Does Meet Me in the Bathroom explore how this was a point of change, in terms of technology? Was that interesting to look at and think about?

DS: One of the biggest draws to do another music documentary, actually, was that. There are only so many stories you can tell about bands, and they all generally fall into the same clichés of drugs and fallouts, and all of that stuff is well-trodden territory. But the thing that fascinated us about this was precisely when it took place: it was this moment that was the cusp of everything changing technologically, culturally, politically. And, even though it’s that rock’n’roll, sleazy scene, there’s weirdly an innocence to it, because nobody knows what’s coming next. And it’s interesting, with the hindsight of where we are now, to look back at that time. It’s one of the things I’ve heard from lots of friends who lived through it, but it’s also always interesting to hear a younger person’s view because they’ve grown up in a world with the Internet, with ubiquitous iPhones, with culture sped up and accelerated to where we’re at now. So I think that time period and the change that was coming was one of the main things we found interesting. And we wanted to leave the audience with a question of: could it ever have happened again? Could we have a scene emerge so organically from a single place at a single time? I suspect the answer is probably no. That doesn’t mean that things won’t happen, but they’ll happen in ways that we’re too old to appreciate now – or just in different ways.

Even the way cities are structured – thinking about Brooklyn and Williamsburg, one can see how cities started to expand at that time and become gentrified, pushing out the creatives and eclectic crowds that were drawn there. It’s similar to London’s creative hotspots expanding from places such as Shoreditch to Dalston and Hackney Wick.

DS: Everyone’s out in Essex now, aren’t they?

How much is it also about that? That these enclaves where creativity can flourish organically just disappear, whether because it’s too expensive for creative people to live there, or it’s too expensive to buy concert tickets – do you think the way cities have changed is also part of it?

WL: I think so. And I think that it was just a perfect storm in this time in New York, because it was still cheap enough in parts of Manhattan to live there and lots of the music venues were still there that hadn’t been turned into whatever they’ve been turned into now. And so Brooklyn, the part of Brooklyn that’s very close to Manhattan, near Williamsburg, that was also cheaper to live in. So I think you were able to have all of these people – whilst they weren’t living in each other’s pockets, there was a bunch of scenes happening in central New York, rather than it now dispersing out just like it has in London.

DS: It just goes on and on, because Williamsburg is probably unaffordable for most people now and people are out in New Jersey or further into Brooklyn.

How do you see our current music scene? Do you think there’s sometimes a bit of nostalgia or a rose-tinted view of the past, when, actually, there is always a spectrum of music out there and alternative scenes forming, just in a slightly different way?

DS: Yeah, exactly. In the space of the 90s, you had the grunge scene emerge out of Seattle; they were always geographically specific. But I think one of the things that perhaps the Internet has done to the way in which we consume and make music – it’s made it less geographical. So I think there’s always going to be stuff and there’s always going to be scenes, but I just think we consume music so differently now. No one ever sticks on an album and listens to it from start to finish in the way that they once would have. So amazing, interesting, creative stuff is always going to happen, but it’s just… will it ever happen like this again? It’s a question.

On one hand, the documentary is a time capsule, but it could also be educational for people who didn’t know that much about that scene; and on another level, you could say it’s inspirational: we need to keep our eyes and ears open to new and different kinds of types of music and not just listen to what we’re fed on the radio. What do you hope people will take away from watching it?

DS: One of the themes that I’ve found most interesting was just how ephemeral those moments can be: those bands all burned quite brightly, but for quite a short time. They’re still around today, and they’re still making music and selling out tours and stuff, but there’s just that moment where anything seems possible when something like that appears. And I think Albert captures it best in the film when he says that you sort of have this thing, and, at the time, you don’t know you’ve got it, and then you lose it. And you spend a lot of years chasing it, trying to get it again, and you can’t. And I think that’s a slightly melancholy note to end on, but I think there’s some truth in that. And I think that’s why our feeling was to capture some of that excitement, but also be quite realistic, because there’s a lot of myth-making and romanticising that goes on in music, particularly in the past. That’s why we opened with that montage that’s got all the romantic mythological icons of New York – Warhol and The Ramones and The Velvet Underground – and I think we close the film again with that, just to ask the question: “Is it possible for the generation that we’ve just seen to become part of that? Or is that a thing of the past?” You know?

WL: Dylan said that better than I could!

And finally, do you know what you’re going to be working on next? Will you be back in the UK? Focusing on a completely different type of film?

DS: I think we probably won’t do a music film next. We’re sort of exploring different ideas, but just exploring at the moment.

Well, it’s been lovely to chat to you. Thanks so much for sharing all that with me. I can’t wait for everyone else to see Meet Me in the Bathroom.

DS: Thank you. Really nice to talk to you.

Sarah Bradbury

Meet Me in the Bathroom is released nationwide on 10th March 2023. Read our review here.

Watch the trailer for Meet Me in the Bathroom here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS