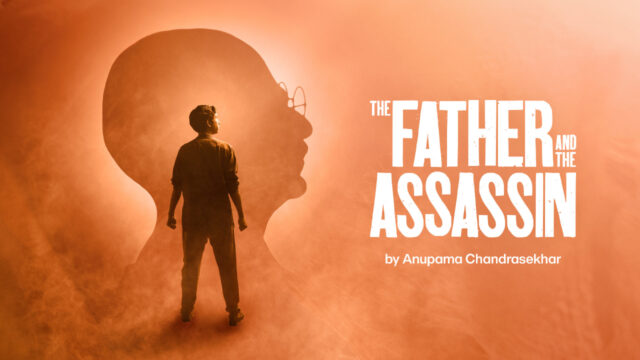

The Father and the Assassin: Anupama Chandrasekhar, Indhu Rubasingham, Hiran Abeysekara and Paul Bazely ahead of opening night at the National Theatre

Written in 2016 by Anupama Chandrasekhar, the first international playwright in residence at the National Theatre, The Father and the Assassin was commissioned and premiered in 2022. It follows the controversial Nathuram Godse’s life and the events leading to Mohandas Gandhi’s assassination.

Marking a much-anticipated return, the play undergoes a refreshing revival from September to October at the National, deftly orchestrated under the discerning eye of Kiln Theatre’s artistic director, Indhu Rubasingham. Chandrasekhar and Rubasingham building upon their successful past collaboration, once again joining forces on stage in a testament to their shared expertise. The latter’s previous directorial successes further validate her ability to infuse this production with renewed energy, resulting in a distinctive and transformative impact.

The esteemed Olivier Award-winning Hira Abeysekera assumes the role of Nathuram Godse with a composed and authoritative demeanour. Adding to this constellation of exceptional talent is seasoned actor Paul Bazely, who revisits his portrayal of the iconic Mohandas Gandhi in a performance poised to resonate both evocatively and indelibly.

The Upcoming gained privileged access to the rehearsal room ahead of previews, for a chance to delve into the production’s mechanics and its exploration of themes of oppression and extremism.

We appreciate the invitation to join you here. Could you kindly share the origins of this show and how it all began?

Indhu Rubasignham: We are in the beginning of the fourth week of rehearsals of this remount of The Father and the Assassin, which was first done last year, and actually Anu would be best to talk about how it first came about.

Anupama Chandrasekhar: I started this play quite some time ago – earlier than 2017 – and, around that time, a new government had taken over in India. Suddenly, the discourse changed and the temperature changed. I was curious to know where all this animosity, the extreme words and language, came from. So when I was doing the research, it took me to the pre-independence, pre-partition days. I remember talking to one of my friends about it; he said, “You have to write a play about that.” Until then, it never occurred to me that there was a play in my head, so I put it forward to the National Theatre, and this became a commission for the NT. And at the same time I was also given a writer-in-residence position, which was hugely useful for me.

To come away from one’s homeland and to write about one’s homeland, you need that distance to understand what is happening in your own country and the world. That distance helped me a lot in conceptualising a first and second draft.

IR: What was also really important is that Anu wrote this play for the NT, so it became about how to make the play speak to a multicultural audience. I saw it as a political play that sits in the cabin of political plays in this country. So, yes, it is very much set in India, talking about specific politics and movements in India, but it comments on a bigger issue – about the rise of nationalism that happens around the globe, so that anyone would find a way to access the show.

When we first worked on it last year, the Ukraine war had started and influenced some rewrites; especially when we were doing the partition scene, the events in Ukraine resonated very strongly. It’s like any good play: it is specific in its context and in what it is examining, but reveals something much more universal. What has been brilliant about doing it now, again… it’s been brilliant revisiting it, a lot of changes are happening, and we have a new lead in Hiran, who is playing Godse.

How does it feel for you, Hiran, to assume the role of Nathuram Godse?

Hiran Abeysekara: It is a mammoth task, and I’m still finding my way through it. I have only just about left the pages on the floor, and it’s now found a place in my mind. It has been an incredible experience. I love being in the room – Indhu is fantastic, and it’s just a happy room. We are dealing with heavy subjects and material, but there is a joy in being in the room, and there is a lot of fun we have trying to find ways of saying it clearly and digging deeper.

AC: What is clear is that, in that room, there is a sense of shared history: Hiran is from Sri Lanka, I’m from India, and there are British Asians around, some are of Pakistani origin, some are Bangladeshi, and some are of Indian origin. There is always a sense of shared history that is humbling. It is a privilege to be in that space with all these people.

Paul Bazely: It will be really different because more than half the cast is new, and people who were in it last time have also changed roles. It is brilliant to walk into a scene and go, “This is entirely different”, so what I do is completely different. Hiran brings an extraordinary energy to the whole thing – it is fantastic and surprising. So it is new in a way I never thought it would be. I’ve never re-rehearsed something like this in its entirety, and it is refreshing. It feels like a full rehearsal, not like we are doing what we did last time.

IR: Yes, there is a lot of rewriting going on, and Hiran brings a really different energy to Godse. There’s a real danger, there’s a real presence there that is really exciting.

What is it like playing Mohandas/Mahatma Gandhi?

PB: Playing Gandhi is phenomenal! What Anu has done so amazingly is, yes, it is a political play in the sense of nationalism and that type of politics, but it is also a political play in terms of personal politics. In modern British culture, everything is polarised, in terms of “Who do you like? If you like them, I do not like you. If you associate with them, you cannot be my friend.” All over social media, we argue: “Whose side are you on?”, “Are you team Johnny or Amber?” – you have to choose your sides, choose your people. What is wonderful about playing Gandhi on this show is that Gandhi is someone who is polarising: some people are not happy with Gandhi in the modern world, some people venerate him as a modern saint.

Anu challenges us to take someone who is beyond the pale – in the play it is Godse, in another place, it might be Trump, or whoever is seen as a villain – and ask ourselves, step into their shoes, follow them for two hours and hear what their story was. Perhaps we’ll feel differently in the end. It’s not a trick, it is making up your mind and maybe thinking about stepping into that person’s shoes, who you would have previously written off as a total villain. For me, that is the exciting thing about this: playing someone who is so well-known opposite the person who killed him, who is the star of the show. Often you see a play and already know what side you’re on, and you almost say, “Oh yeah, I’m with the good people here, and it’s cosy.” This play invites you to go, “Well, not really, and maybe not!”. And that’s what I like about it.

We saw the show last year. Who is it targeting this time? Is it geared towards those who’ve already witnessed it, or those who missed it previously? Who’s the intended audience?

IR: I want people who saw it before to see it again, because I think it is better on many levels. Being able to be in the room and do it again means that I am better. When we first did it, we did not even know whether it would work; now, we know it works, and people are contributing different things to it. All of us – from the movement, sound, and lighting – are wondering how to refine it, do it better, and make this powerful. How do we communicate the story? Ultimately, we want those previously unable to see the play to see it. It was on for such a short time, so for the NT to program it once more allows us to reach a wider audience. The opportunities are endless. The number of people who did not see it before and want to now is outstanding. Before I went into rehearsals and I started working with Hiran, I would have said it is all for the new people to come and see it. Now I want everyone to come and see it because it’s so different from last time.

PB: Also, Indhu gives me notes, and I think about how I never thought of that last time. How did I never think about exploring that thing yet? So it is astounding when you come back to it a year later and find that, even though you thought you knew the show before, there’s lots of new stuff to explore.

IR: There are even two bits that Anu will rewrite, right now! And that’s what’s wonderful about theatre: you only create it with the people who you have in the room and their experiences. The mistake would be to try emulating what you did previously, and not see that it is a living, breathing thing. That’s why I love theatre, because night to night the shows are not even the same, because the audience is not the same, and the energy they give and reactions they have help to paint what we do and how the show evolves.

AC: I want everyone to come and see this show and start conversations they never would have before. I want the audience to take this home with them. Our world has become far too polarised and we are not listening to each other; we have opinions, but we are not allowing other people to have a different one, to mould our debates. Any idea – any thought – has to evolve, it has to have its dance with other ideas. In this world, we are stopping that dance, it is a solo move that we are doing, and, ultimately, that is not good for humankind.

I’m curious about the impact of last year’s response on your rewriting process. Are you primarily considering in-house notes and theatrical elements, or does the audience’s unexpected take on Godse play a role in shaping the script anew?

AC: I have tried to be truthful to my original impulse, which is to see Gandhi through the eyes of his opposite, because that is the way our world is now. In a polarised world, to see someone else through the eyes of his antagonist I thought would be the best way to introduce both arguments. Have I been influenced? A little bit, yes. But, in the end, I have tried to be truthful to my original impulse because you cannot please everyone. The one you can please is the person who started to write: me. It would have been great to have achieved everything I had wanted the last time, but it wasn’t, for whatever reason, because perhaps I wasn’t evolved as a writer. One year can make a lot of difference in that aspect.

IR: I’m going to correct you. It’s not about your original impulse – a lot of rewrites went into the original rehearsals last year. It was a way for Anu to fine-tune her work, but we were not influenced by the audience. I had people telling me, “We like Godse, and you’ve been too nice to Gandhi,” and that’s what’s good about the play, because you had people reacting in vastly different ways, and there was no overwhelming one side. It’s good that people came out conflicted.

AC: Conflict is always good. If you enter a show with one set of ideas and you exit with the same set of ideas, then we are not doing our job right.

IR: Much of the rewrite is because things are getting deep in the rehearsal room. For example, the actors are excavating and going deeper. It is making the creative team see that we are missing a beat in some places, or that we need to do more. We have actors bring more to the piece than we could on our own.

Given the play’s multitude of characters and historical backdrop, how do you strike a balance between the intimately personal human narratives and the broader historical message encompassing India as a whole?

IR: I think there is a very simple answer: that’s theatre. That’s the beauty of theatre – using a very personal story to tell a big political story. If it was all about politics, this play would never have been programmed. We need to emphasise and we need to follow; all the best big plays have the emotional journey that you follow. It is important to say this is Anu’s play: it is not representational, it is not trying to say everything, it is a new play condensing more than 40 years of history into two hours. When there is such a lack of representation, the onus can be on the things we haven’t included, but that is not the pressure that should be put on Anu. It is not pressure you’d put on a white playwright, so why put it on Anu?

I know you combine fact and creative interpretation – how did you pick and choose?

AC: There were a lot of permutations and combinations that we tried, and it was difficult to know which events to choose. Finally, we went into rehearsal last year and included the events pertinent to telling the story. But it did take a lot of time. If we’ve not dwelt on an event, it is because it didn’t suit our purpose, not for lack of knowing.

IR: It is hard to combine it.

AC: It was twice as long a play when I first finished writing! Clarity was important and central for us to make it accessible to those who weren’t aware of the history of the region.

IR: That’s why the play was meant to be produced here, so it had to be accessible to an audience who knows nothing about Indian history. That was the balancing act.

PB: Also, if it isn’t relevant now, there’s no point in putting it on. If it was a history lesson, you could watch a documentary. Shakespeare wrote his histories not really about the titular characters – he was trying to find a way to talk to his audiences then, [he] thought about the past, and invited them to see what it says for them today, now, and what it makes us think about. And that’s why it was so nice when so many young people came for the first time and talked about how it made them think about their heritage, but also about what is happening online, for example. Someone here who works in the bookshop had taken the book back to Libya and translated it word for word for her family because she saw it was so relevant to the situation in Libya at this moment. We could never have anticipated that.

IR: On the first preview there was a group of people from all over the world, and there was a big discussion going on about the politics in their own countries, and that was great. That’s when you know it is not limiting and it’s making people talk about what is going on wherever they’re from.

Anu, how did you bring Godse to life, considering the limited Western references, and how did you ensure his portrayal resonates with the audience?

AC: There isn’t much written about Godse in India, so I tried to find whatever I could about him. Of the two sources I used, one was written by his brother, who was part of the assassination group that Godse had cobbled together. A few things he mentioned, one of which is Godse’s childhood – not in great detail, but the way he was brought up, as a girl, with the nose ring, to appease the goddess.

A little bit about those things: in a way, there is an advantage in not having very much material, because Gandhi was where I had a problem, because there are reams and reams written about him, because either he’s a saint or he’s a devil. Gandhi the man was very hard to find in those books. I read over 100. Godse was much easier because there wasn’t much written about him.

IR: I think that you’ll find, I’m just reminding Anu, if I remember rightly, she knew about the young period of Godse and also much later before he assassinated Gandhi, and what he said in court.

AC: But then I used my imagination to fill in the rest. So there is the youth – we know that he met Savarkar in Ratnagiri, then it comes to where he’s in his forties, when he starts to agitate against the Gandhi movement. So I had a lot of blanks to fill in, and I had to use my imagination to fill in those blanks. But, yes, another important source was his defence in court. In many ways, the framing device is influenced by those very defence points, and hopefully I have been able to give the historical context to what he says to give both sides. It is not Gandhi’s voice alone, but also Godse’s in the play. That is something I have always wanted as opposed to the other – a balance of the two. In opposition, the play is a play about opposition.

Hiran, how do you approach the emotional and psychological evolution of Godse’s character in the play, especially considering he’s a murderer? How do you delve into that mindset?

HA: I’m still in the process of discovering what it’s like to portray him. Dealing with it involves understanding what drives someone to commit murder. We often express extreme thoughts about people, like saying, “I’m going to murder them,” but we don’t act on them.

I was born during the civil war in Sri Lanka, and there have been numerous tragedies there. I experienced personal losses during the Tsunami as well. As a child, one of my earliest memories is the assassination of one of our presidents by a suicide bomber. I remember being at my grandparents’ house, hearing fireworks, and seeing them celebrate the news of the president’s death. This left me confused because I was taught that killing is wrong, yet the people who taught me specifically this were now rejoicing over someone’s death.

Reading about Godse’s story brought back this memory. Anu mentioned how statues and even a temple were erected in Godse’s honour; it made me wonder why we are often drawn to individuals who have taken a life. Perhaps it’s the ultimate act of rebellion against our nature and conscience. In our society, we generally coexist peacefully, unlike in the animal kingdom where killing is often instinctual for survival. Yet, there are instances of individuals committing murder. In Godse’s case, was it hatred for Gandhi or a desire to prove something to his family, figures like Savarkar, or even to himself as he embarked on a journey of self-discovery? Despite his heinous act, my goal as an actor is to uncover the vulnerability that led him to commit such an awful deed. This aspect fascinates me in the rehearsal room and my portrayal.

As for managing the mental space required for this role, I’m still working on it. There are scenes where Indhu has guided me to a point where she believes I can convincingly portray someone capable of murder. I’m still navigating this process. We ran the first half today, and the more I delve into the character, the more I understand his journey. I’m confident I’ll have a clearer answer soon. For now, I’m focused on uncovering what drove him to his actions.

Paul mentioned earlier that the concept of being a patriot is rigorously monitored and subject to continuous debate and critique on a global scale. Does this play explore the question of what it truly means to be a patriot? Not only in the Indian context but also in a broader global perspective: what does patriotism entail or represent?

IR: I’m Sri Lankan, so one is slightly distanced in that sense. The way I would answer the question… I think that patriotism and a sense of identity are more in the room than in the play. By that I mean there is real pride in the company of people doing this play, in this theatre, and everything that stands for. These stories are being told. What would happen in the rehearsal room is that people would bring up their stories. It’s ironic because the patriotism of the Indian subcontinent is coming from colonialism, and that wasn’t handled very well. The way the play deals with it is a very double-edged sword. Gandhi (Paul) has that line to Godse where he says, “You’re killing me over nations that are only a year old.” This always hits me because these two countries are so young after independence, and were carved up quickly and randomly by the British, which Godse talks about. So, for me, the play pulls apart and makes us question what that is.

PB: It changes all the time because they are just constructs. So you can be attached to your place, land and people, but when you start saying, “I’m a Russian-speaking Ukrainian who either wants to be a part of Russia or doesn’t,” those are just concepts. Like Pakistan and India. Like does Northern Ireland become part of southern Ireland? Or whatever the thing is, you start to get into abstractions. What does that mean? For British Asians, and for anyone who lives in this country who has cultural heritage somewhere else… My parents were born and bred in Chennai, but I was born here, for example, but I’ve always felt there has been a part of me that hasn’t been seen as part of home in the only place I’ve ever called my home, and a lot of people in the cast feel that way. As time goes by, these things become more and more complicated, and it is easier to go, “I’m not like them” or “I’m not like you” because more and more fractures appear. Even in London: are you a south Londoner or a north Londoner? For people in this country whose skin colour is different, you have a different set of questions you have to ask again: what does it mean to be what you are? It is a valid question to keep asking, but in a spirit of curiosity rather than judgement.

IR: What the play does is that it juxtaposes that concept. There’s the celebration of the independence of both, and the creation of India and Pakistan, and then, within a minute, you’re seeing the effect of partition. In a new scene, when Godse is confronting a Muslim customer, Godse says, “When you’re in our land, you have to do this,” and the character says to him, “I’ve been here for five generations, you have just moved here.” Who has the claim and ownership – who is the true patriot – is challenged. Even Savarkar mentions it. If anything, the question being asked is what makes you a patriot and what defines the word.

The scarcity of plays centred around Gandhi is often questioned, raising concerns about equilibrium. With the focus on two pivotal political figures in Indian history here, where does the equilibrium lie? Could there be an alternative artistic or cultural interpretation familiar to audiences?

IR: I come from a place of developing work with playwrights, and I fight for anyone that’s from a minority culture not to have to be representational. They can write what they want to write, so I will always fight for that for a playwright, no matter their background. So I think it is a hard question to ask this group of people, but I could also say to you that The Empress is on at the RSC, Silence at the Donmar last year, and there’s Tineka’s play that also exists. If people are angry about it, writing the play has done its job by inciting a response. I think the answer is getting more people writing – I mean half our cast are writers! What is important to remember is it’s happening.

When we went into lockdown, I never thought that the NT would kill The Father and the Assassin because of its niche subject matter. I don’t think there is a theatre in the world that would put on a play on the scale that the NT has done with The Father and the Assassin, with over 20 actors, from a writer from a different country. I cannot think of anywhere they’d do that. So the fact this is even happening is a brilliant moment, which – yes there need to be ten million other plays, but it is something that will inspire other playwrights. Other artistic directors will see the NT having done that, and they will in turn have the courage to commission the play they may be a bit nervous about. The level of apprehension was that the NT was putting on a play about Indian history on the Olivier stage. There was apprehension because that was a big platform. That it has worked can only benefit the industry and the communities.

PB: It is always a worthwhile question to ask because it is important to pressurise people to not become complacent, and for the management to go, “We’ve had our brown play, so we don’t need to do anything like that for a while.” But it is an interesting question to ask because a white writer would never be asked that question. No one is asking Christopher Nolan for the other perspective on Oppenheimer, or no one is saying, “James Graham, you’ve written about the England manager but what about x, y, or z?” – they’re free to write about whatever they want, because they have that sense of entitlement. Black/Brown people are told they have to represent their cultures, which puts pressure on them, which the white artists don’t have. It’s a double-edged sword. It’s right to ask where the others are, but also to say, “Write what you want.” Minorities should have the same freedom as the majority.

Natallia Pearmain

Photos: Marc Brenner

The Father and the Assassin is on at the National Theatre from 8th September until 14th October 2023. For further information or to book tickets visit the theatre’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS