“I like to think of my work as a conversation”: Samuel Rees on Lessons on Revolution at Edinburgh Fringe 2024

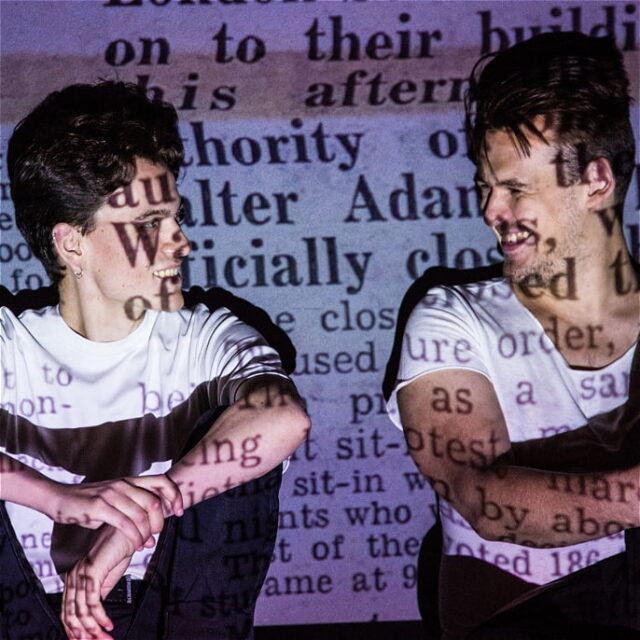

A small piece once performed at The Hope Theatre in October last year now finds new life at the Edinburgh Fringe. Lessons on Revolution, created and performed by Samuel Rees and Gabriele Uboldi, recounts the sit-in protest in 1968 at the London School of Economics. It explores the string of fate that ties that one local slice of history to the massive international events that took place in the 60s – from the Rhodesian War and Vietnam War to the Gay Liberation Front. Taking the form of a conversation between friends and a behind-the-scenes look into the research that goes into making a play, Lessons on Revolution prompts viewers to question their role in creating positive change in a world riddled with failures and hopeless truths.

Lessons on Revolution is a real-life example of how something minute and simple can snowball into something bigger, with the potential to resonate with many different people. Its focus on revolutions that failed rather than success stories from across history perfectly captures the enduring effort of everyday people who want to create positive change and make their own mark on the world, yet constantly face rejection and hardship. This vivid reflection of the grander picture of historical change against people just trying their best to live, thrive and survive, is where the excellence of Lessons on Revolution lies. The Upcoming caught up with one half of the creative duo, Rees, to discuss the initial catalyst for the play, the collaboration process with Uboldi, the significance of The Hope Theatre as an initial venue and the show’s transfer to Edinburgh Fringe.

Can you give us a brief introduction to your upcoming show at the Edinburgh Fringe, Lessons on Revolution?

Part of it is the story of the 1968 student protest at the London School of Economics where students occupied the library at the school in protest to the university investing in apartheid regimes in Africa; part of the show is also an exploration of mine and Gabriele Uboldi’s own lives and our place within the history; another part of it is a kind of examination on what theatricality and what performance actually means. There’s lots of exploration of meta theatre in it, lots of exploration of what a play about making a play looks like – there’s lots of commentary on our research and the stuff we decided to miss out on. We try and spin that into a wider conversation about whether it’s possible for art to change the world and use it as a mechanism to question the extent to which we actually help affect positive change, or if it’s even feasible for us to do that. There’s a lot happening in the show because, on top of that, there’s also this constant dance with the audience as well. We get them to read out historical documents and we cast them as characters in the historical story of the play. The relationship with them is the actual key to the show. A lot of shows will talk about how much they need their audience and, on this occasion, it couldn’t be truer. The show can’t happen; it’s an event that needs an audience and it isn’t fully complete until the audience are invited to make this active collaboration with us and help us tell the story.

What was the initial catalyst for the making of Lessons on Revolution? Who sparked the idea – you or Gabriele?

I read a book about 1968, which was a massive global event. They were protesting an uprising and there were various activist movements across the world that year. I got interested in some of the experiences being made within this book, which was an archive in itself about that year. Collaboration for me is a massive form of the style that I do. A lot of the time, my friendships are formed through an interest in connecting through creating stuff together. Finding the right person to create an idea with is always really key to me. I’m interested in what happens when my work and someone else’s work collide, and what the product of that is. On this occasion, it felt, as I was reading [the book] and kind of having various hunches, that Gab might just be the perfect person to broach that with. Although it was my foundational idea, he was on board and was in the conversations and in the consideration of the piece very early on. It feels very mutual.

You talk within the play about the research that went into making this piece and even mention some of the things you had to cut out. Was there anything that didn’t even get a mention in the play?

Like, it didn’t even get a mention of not being in the play? Well, nothing springs to mind specifically. But that did prompt in my head that initially, I was interested in exploring the global movements of that year. It probably lasted for all of five minutes but initially, the play was going to be an exploration of stuff that was happening in Asia, or stuff that was happening in South America, and all these different places. I eventually realised that that was completely unrealistic, not something we were equipped to do, and probably not something that anybody could do adequately within an hour of theatre. We zoned in very quickly on London – our local area and what was happening there. But at the same time, the ghost of that initial idea is all over the show. You see that in the show, there’s still an internationalist perspective there. Wherever we can pull in an international context to what’s happening in London at that time, we kind of do. The play spans about four continents still, it’s just that it has a much more focused exploration than it initially did.

You mention Gabriele as the perfect person to do this with. Did you have any moments of disagreements with him throughout the creative process of Lessons on Revolution?

In a collaborative process, I thrive off debate, discourse and hashing things out. In some ways, the edge to both our personalities – which can be at times combative – is also baked into why I thought he was the right person for it. Because I wanted someone who could hold me to account. Something we both said about the other is that we both got rid of each other’s sh*t ideas; we both stopped each other from doing quite stupid things. If we’d been left to our own devices, there would’ve been wrong decisions that no one would’ve told us that we didn’t have to do. [The difference] wasn’t in a way that wasn’t generative or productive. I think, if you’re doing something that you care about, and you think it matters and that it’s important and worthwhile, then a certain level of disagreement is baked in that. But nothing that ever felt it got personal or we couldn’t ever come back from. I think we both kind of thrive off of challenging each other.

The Hope Theatre, where the play was first staged, seemed like the perfect venue, given its message of revolution, change, failure and “hope”. What was the process of acquiring that venue?

To be honest with you, there are a couple of things there. One of which is that there’s a certain level of reverse-engineering that happened where I had a good relationship with the AD of The Hope at the time. Particularly, if I had a new piece that hadn’t been tested yet, he would probably be amiable to having it on there – as long as it didn’t sound abjectly awful. In that sense, it kind of could have been anywhere. However, the really important thing to bear in mind [when we were] at The Hope, was what possibilities can be contained within that space? In terms of the physical make-up, for instance, the chairs were moveable at The Hope so we got to experiment with quite crazy staging and seating arrangements where the audience were sat on cushions on the floor. We also got to think about the location of the place and what that meant. Also, we got to investigate an area of theatre-making which really interests me, which is, particularly at pub theatre and fringe theatre level, creating work that is clearly not fighting against the constraints of that place but embracing them. Maybe if we acknowledge that we’re in a small room, that hasn’t got the most complicated tech set-up, isn’t sound-proofed, all these things that people see as a hindrance – I think there’s a huge amount of possibility in embracing them. All of which is to say, once we knew we were in The Hope, it was absolutely imperative that we think about The Hope as the place for it. That’s kind of continued throughout the rest of this. Because wherever we are, we sort of have to think about how that changes the piece and what new version of the piece it now is. Because it’s literally baked into the lines of the show – we discuss the venue that we’re in that day and what the nature of that venue is and what you can hear downstairs, what you can hear outside or whatever. It’s just right there, front and centre, all the time in the show.

With moving from venue to venue, from The Hope Theatre then to Soho Theatre in London, to now being at the Edinburgh Fringe, was there any further research you had to do and add to the show to incorporate the new locations?

No, when we performed at Soho, there was actually a strange type of research that happened with that: because everything was kind of in our hands at The Hope, and we could stage it however we wanted, we sort of knew that if we ever went somewhere else, we would have to refine it to work in a more traditional “theatre” space. In that sense, Soho was a really vital part of that process in [working out] what it feels like in a room that’s a bit more put-together, and whether it can work as an end-on piece of theatre. I don’t necessarily know where we landed on that, but it was a really important investigation for us to do. In terms of the actual history of it – no. But there’s something that is really interesting regarding us having to consider more of its relevance to now. For instance, right now, the LSE Student Union are occupying the library again because of a protest against the university’s investment in Israel. Aside from the normal clichés about history repeating itself, it’s also really, really important that we work out our position in that. Not from a promotional marketing perspective, but because there’s an authenticity in the heart of the show that means that we are obliged to discuss what’s happening now – not within the show itself, but in a broader sense. Because if we just put our fingers in our ears and pretend we just read a piece out of history and what actually is happening now has no bearing in it, the piece completely loses its vitality. There’s no actual additional material within the context of the show. But there’s always a conversation occurring about how the world – as it changes in real-time – is impacting what we’re doing and how we present our work.

Why was it important for you to focus on protests that didn’t work or had failed?

Something I’m particularly interested in a show is the idea of failure. What intrigues us as well about that is the idea that failure is a political thing but also an artistic thing as well. In some ways, we answer that question in the same way. So, whether we’re talking about a protest or creating theatre, there’s this notion of perhaps a kind of objective success or lack thereof in any particular endeavour. It’s not the point; the point is that what you have done is create a glimmer of light for a moment in which you can imagine something better. There’s an important utopia as it’s happening within the context of what is going in the 1960s at LSE and also the simple idea of – is it worth putting on a show in the first place? In both cases, perhaps one could argue, the state of objectives of those activities were not met. But what did happen is there was a space created to imagine a better future. Without that kind of prefiguration of the idea of working out and creatively imagining what the world might look like if it were a better place, then that future won’t ever come, right? Failure is a useful means to formulate your thinking.

When you began working on this project, did you ever think it could snowball into something bigger? Do you have a new appreciation for Lessons on Revolution now that it has reached the heights it has now?

I think if anybody has any sort of even subconscious dismissiveness or condescension towards pub theatre, it’s a really good example of why that’s a silly opinion, [of] why the stuff that’s happening in these places is viable and can have a future life. It’s such a low-risk avenue; it’s a cheap night out and you’ll either get something that you don’t like and it’s over in an hour, or you might have your life changed for a tenner. It’s an amazing way of experiencing new work and it has given me a new appreciation of that, for sure. I think the thing about the show itself is that we give so much power to the audience. It’s always kind of hard talking about that because it’s one of the show’s interesting selling points, but at the same time, it requires you to spoil it. Sufficed to say, there are moments at the end of the show when the audience’s autonomy is almost total and we kind of abstain from the show. It’s put in the audience’s hands. Because of that, it means every time that we do it, there’s a new colour and shape to everything. [The audience] hear everything anew because people will bring their own shape and their own ideas about the world to it. I like to think of my work as a conversation. It involves a mutual exchange of experience between myself and the audience. In that way, you hope that no matter how rogue and dry the work becomes for you, the audience’s side of that conversation will always provide you with something new and exciting. That’s the way I learned to appreciate it over and over again.

Mae Trumata

Photos: Jack Sain

Lessons on Revolution is at Summerhall from 1st until 26th August 2024. For further information or to book visit the theatre’s website here.

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS