“He’s not just a victim, he’s part of the problem”: Sean Wang on Dìdi

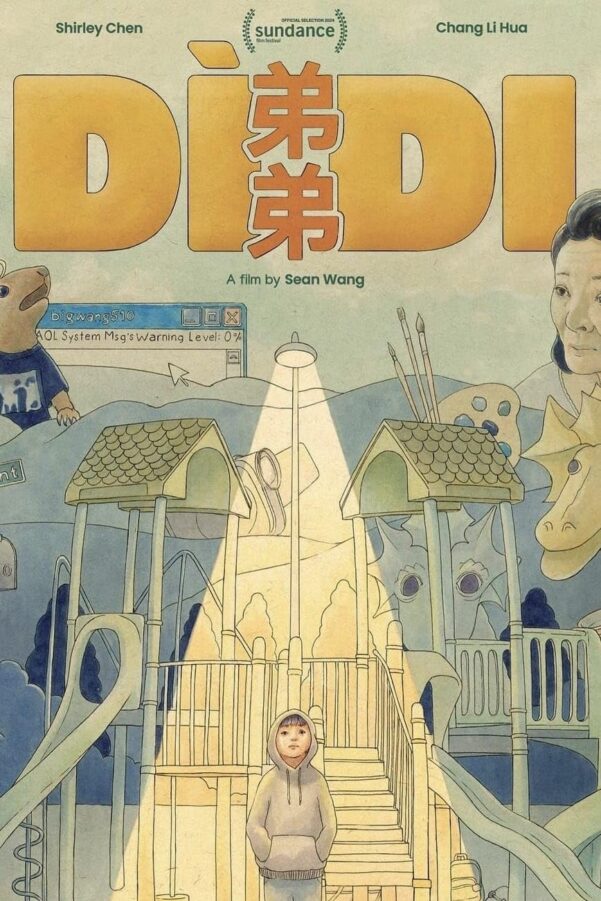

A sort of time capsule for the late 2000s teen experience, Dìdi is an incredible coming-of-age film that truly captures the anxiety, peer pressure and social environment of that period in a young person’s life. Starring Izaac Wang, whose credits include Raya the Last Dragon and Clifford the Big Red Dog, the film is not only a goldmine of early social media and content creator culture references, it’s also a very poignant and nuanced story of a boy learning to grow through life, navigating family, friendship and blossoming relationships, on top of overcoming haunting loneliness and struggle for genuine self-acceptance. Funny, immersive, sentimental and extremely impactful, Dìdi is a simple yet beautiful cinematic experience.

Director and writer Sean Wang has recently been nominated for an Academy Award for his 2023 documentary short Nǎi Nai & Wài Pó, featuring his paternal and maternal grandmothers as they go about their daily lives. Now, he further proves his ingenuity as a filmmaker as he debuts his first feature-length film Dìdi, one whose main character Chris he imbues with pieces of himself – his affinity for filmmaking and skateboarding. The Upcoming caught up with Wang in an informative discussion regarding his film, from the autobiographical aspects of it, the culture and identity clash as an Asian growing up and assimilating into a Western environment, incorporating problematic slang into his script, and the importance of creating an enjoyable film set experience for the young actors first starting out their careers in Dìdi.

This film is very immersive in dropping the viewer into the 2008 time period and culture. Was it fun trying to recreate that and deciding which references you wanted to showcase in the film?

Yeah, it was! There’s so much about that era, the internet and little sort of things that trigger certain memories and nostalgic dopamine hits for people. Like, “Oh, I haven’t thought of that in a million years.” It was fun trying to figure out what did certain things for people.

About Chris’s experiences throughout the film, were they a little bit autobiographical? Were they things you also went through while growing up?

A little bit. But in writing, I think it just becomes its own thing. I was a skater – I am a skater; I made skate videos. Chris is a different, meeker, less self-aware version of me. He’s a character in that he’s definitely me to an extent and I also see a lot of myself in him. But I also see myself in every character.

Specifically his struggle in trying to assimilate into the Western culture that surrounds him and the Asian traditions that he grew up with, was that something you also experienced?

Yes and no. I think the feeling we were trying to capture is one that’s ambivalent. I don’t know that he even really knows that he’s trying to distance himself from certain things that had to do with his culture. It was more felt than it was active for me. When people say things like, “Oh, you’re cool for an Asian,” or “You’re cute for an Asian,” or “You’re the coolest Asian I know,” it was a compliment back then. It’s not until, for me, like in my 20s that I look back and I realised that kind of really affected the way that I looked at myself and the way I looked at the world. I don’t know that it was so explicit and such an active choice. You know when people say, “You’re the whitest Asian I know,” well, what does that mean? Like, what does that mean about my identity as an Asian person? I didn’t have the vocabulary for it when I was a kid and I don’t think Chris does either, but we do now. That’s kind of what the film tries to do. It’s like, presenting things as they were but watching them now. Those kids grew up to be people like you and me, and I think we have the perspective now to kind of analyse the things that happened back then and be like, “Oh, interesting. I do remember that and I don’t think it was very good for me.”

Speaking of language, hindsight and perspective, you have included in this film the common slang people used, some of which were slurs, others using the word “gay” as an insult. Were you nervous putting those in your film or did you feel it necessary to really capture the problematic aspects of that time period?

I wasn’t nervous but I was definitely aware. It wasn’t lost on me. I didn’t want to be gratuitous with any of that language but I did feel it was necessary to show some of the things that we just kind of accepted back then, show what was normal in the culture and that was part of it. If we’re going to show the pain and the shame that Chris goes through as a character, and the toxicity of what he goes through and what he also does, it was kind of important to me that we had to show that it wasn’t happening in a vacuum. This was what the culture was like at the time and the cultural standard was different for everybody. We had to unlearn – not just as an Asian-American kid – what did we have to unlearn for ourselves? What are the things we had to unlearn as a culture? He’s getting things said to him like, “You’re cute for an Asian,” but he’s also saying stupid shit too. He’s not just a victim, he’s part of the problem. All the kids in the film are part of the cycle and we had to unlearn all of it. It was important to show it but not be gratuitous with it. There are films that are like, “Oh, it’s a period piece so we’re just going to say whatever we want.” I didn’t want to do that.

You talk about Chris being a character that you also see parts of yourself in but also something that came into its own. How much of Chris was also Izaac Wang’s portrayal of him? How much of that was something he made his own as well?

A lot of it. Izaac is not Chris. His performance in this is a performance. It’s so good, calculated and chiselled. Izaac is more like a self-proclaimed cool and confident person – and he is. Even those parts were like the very initial shaping of the character with him. We improvised a lot in our very early chemistry reads and he would kind of get a grasp of the character and who Chris was. Every time we would get into an improv thing, you could just sense that he’s not Chris anymore and he’s Izaac. He would be so confident! It was kind of that and how do we shed this and have him really embody Chris’ headspace so that even when he’s improvising, he’s improvising as Chris? He’s very different from Chris in the film and I think it just goes to show how brilliant of an actor Izaac is. His performance is so lived-in, nuanced and natural.

With Izaac, you two have this parallel dynamic of he’s just starting out his career as an actor and this is your first feature-length film. Was there any mentorship dynamic at play in your relationship with Izaac throughout the process of filming Dìdi?

I don’t know that we’ve ever talked about it but I care a lot about him. I’m really excited to see where he goes from here. That’s kind of a gift within the movie that all of the kids – some who were first-time actors and are now interested in acting – for our film to be the first for so many of them. For me as well and a lot of our crew. I’m excited to see where he goes from here and where all the other kids go from here. The ones who want to continue acting or even the ones who don’t. I was really careful to make sure we were giving these kids a good experience. To not wrangle them into this infrastructure of filmmaking and then have them be like, “That wasn’t cool, that wasn’t fun.” It was really important to me that all these kids had a lot of fun in this shoot and that even if the movie ended up sucking, that they could walk away with a core memory and be like, “Whoa, what an insane experience that just came out of nowhere!” One that they could create lifelong friendships and look back at ten years from now and be like, “Wow, that was really special.” But I’m glad the movie’s also good!

Mae Trumata

Dìdi is released nationwide on 2nd August 2024.

Watch the trailer for Dìdi here:

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS